The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is considering opening up hunting on Trumpeter Swans.

In 1936, T.S. Roberts wrote that "The days of the Trumpeter Swan as a bird of Minnesota have long since passed." His research indicated that Trumpeters had formerly been found throughout the grasslands and sparsely wooded regions of the state, but were hunted until they'd been wiped out in the state “even in advance of the destruction of the Passenger Pigeon, buffalo, and antelope.” The last breeding Trumpeter Swans in Minnesota were recorded in 1883. Roberts traced all specimens labeled as Trumpeter Swans taken in the early 1900s, and sadly confirmed that every one of them was actually a Tundra Swan. According to the Minnesota Breeding Bird Atlas, "By 1932 the population was on the verge of extirpation in the entire lower 48 states. Only 69 birds remained in and near Yellowstone National Park" (near and in the Red Rock Lakes).

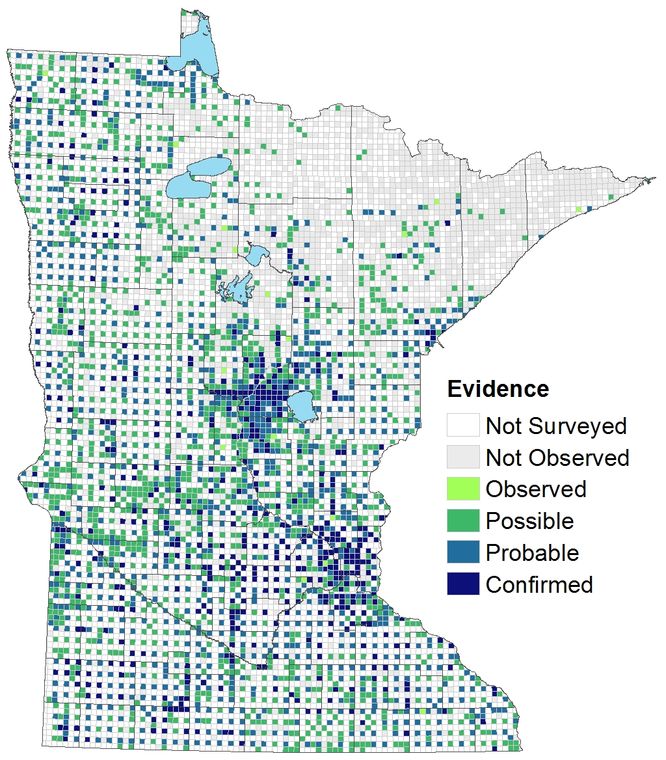

A few summering swans appeared in Minnesota in the early 1960s, following the 1960 release of 20 cygnets into the LaCreek National Wildlife Refuge in South Dakota from the Red Rock Lakes. That gave hope that a reintroduction in Minnesota could be possible, so in 1966, what was the Hennepin County Park Reserve District tried releasing 40 Trumpeters from the Red Rock Lakes there, but the birds disappeared; attempts showed more promise a decade later when people reared cygnets in captivity for 2 years before releasing them. Birds from this project were first released in 1978, and the very next year, there was successful breeding in Minnesota. When the Minnesota DNR Nongame Wildlife program began, reintroduction of the Trumpeter Swan was one of the projects that made the chickadee checkoff for donations so successful.

This exquisite bird that had been wiped out in the state by hunters in the first place is in jeopardy even today and, tragically, its problems are still due to hunting. According to the Minnesota DNR's Trumpeter Swan Restoration Project webpage, the main cause of mortality for Trumpeters in the state is still from lead poisoning from swallowing lead shot and lead sinkers. Lead poisoning is especially prevalent during droughts, when low water levels have the birds dabbling through the muck in areas of lakes usually too deep for that, where lead shot still lurks on the bottom from long, long ago. When swallowed as grit, the swans' gizzards grind it down and send it straight into the bloodstream. Lead pellets remain on the ground or in the water like tiny time bombs—indeed, some swan poisonings have occurred on lakes where no hunting has taken place in almost a century, because ending the hunting does not magically make the shot already present disappear. Lead sinkers are the other cause of lead poisoning in Trumpeter swans.

Many hunters fought strenuously against banning lead shot for waterfowl hunting even as some hunters proposed the ban in the first place and fought strenuously for it. Enough hunters still resist any regulations about lead shot and bullets in upland habitat that it's still legal to use it despite how serious the problem of lead poisoning is for wildlife and for the hunters and their families as well. Grit-eating birds, including waterfowl feeding on grain fields, still ingest lead, and lead in gut piles and in any wounded game that eludes the hunter is still poisoning eagles and other scavengers.

The second biggest cause of swan mortality in the state is from illegal shooting, sometimes by hunters mistaking the swans for other species, a serious hunter education issue, and sometimes intentionally, by poachers and vandals. The penalty is clearly not strong enough to serve as a deterrent. One hunter who shot a Tundra Swan in Lake of the Woods faced at most a $375 fine, and no threat of losing his firearm or his hunting license.

Collisions with power lines are another issue facing the swans, and also a lack of funding, which has become a problem for the DNR in general. Right now they don't even have funding to continue battling invasive species, and the Trumpeter Swan restoration program is not as dire a situation:

Funding for trumpeter swan restoration is an ongoing need. Minnesota's Trumpeter Swan Restoration Project is funded by the DNR Nongame Wildlife Program through donations from taxpayers to the Nongame Wildlife Checkoff on state tax forms. Additional funding comes from direct private donations.The DNR Nongame Wildlife Program's funding via the "chickadee checkoff" on our state tax forms began in 1980. I was one of the people who tried hard to publicize the Chickadee Checkoff via my radio program. Just during the 1980s I did three programs specifically about our Trumpeter Swan reintroduction program:

- In 1987 I did a program about the Chickadee Checkoff mentioning the Trumpeter Swan among other species whose recovery it funded. 1987 radio program.

- Also in 1987 I did a program about hunters shooting swans, and how much the Nongame Wildlife Program spends per bird for their restoration.

- In 1989, I did a program about lead poisoning in Trumpeter Swans in Minnesota, and how expensive it was for the Raptor Center to treat them.

As one of the original projects funded by the DNR Nongame Wildlife Program, people in the state of Minnesota have had almost 40 years to internalize that indeed, swans are NONgame wildlife here in the state, and many of us have donated to the chickadee checkoff specifically to help these splendid birds. Now, as the state considers opening a hunting season on swans, many of us who donated to the NON-game Wildlife Program feel betrayed.

Of course, the Minnesota DNR Non-game Wildlife Program has already shown its disregard for the concept of NONgame wildlife by designating the Mourning Dove a game species here in 2004. Nationwide, the dove is the most heavily-harvested game bird, but hunting had been closed on it in Minnesota since 1947. In the forested northeastern part of the state, Mourning Doves are at the extreme northern limits of their range, with nowhere near enough population to support a hunt. Birds in my neck of the woods are here only because of backyard bird feeding. It's true that the Mourning Dove didn't receive any nongame funds to restore its numbers, but neither did it receive funds for game management in the state; its population is thriving thanks to agriculture and backyard bird-feeding.

Changing the dove's designation to a game species here in Minnesota created a dangerous precedent. Duluth Audubon and I personally beseeched the DNR to prohibit hunting in the northeastern part of the state where the population is very low. And the north shore is an internationally significant hawk migration corridor where flying American Kestrels are often misidentified as doves. Hunting of several species in the state is restricted to some management areas, and this seemed very reasonable for dove hunting. The state's new Breeding Bird Atlas provides confirmation that doves are too rare in this part of the state to support a hunt.

We also requested that as a brand new hunt, dove hunting in the state be restricted to non-lead shot. I provided citations from the annual US Fish and Wildlife Service's Mourning Dove reports to show that doves themselves suffer from exposure to lead from wasted shot, as well as information about how lead even in upland habitats was taking a toll on other species.

But the DNR went into the hearings listening ONLY to hunters who wanted the hunt; they pooh-poohed both these requests out of hand.

When the Minnesota Non-Game Wildlife program began, a few cynics said it was a ploy to get non-hunters to donate money to bring back species that would then be designated game birds, but most of us rejected that cynicism. Unfortunately, in the case of the Sandhill Crane, the cynics proved correct. This species was made a legal game bird in the Northwest Region of the state, the very region where it is still used to encourage people to support the Nongame Wildlife Program!

The huge increase in Sandhill Cranes in our area was due to a huge, concerted effort led by the International Crane Foundation and several other non-profits and colleges, spearheading an annual crane count and researching the species' needs. And contributions to the DNR Nongame Wildlife Program were part of their recovery as well.

|

| Breeding Bird Survey shows massive increase in Sandhill Cranes in Minnesota. |

Farmers have had some difficulties with cranes feeding on planted corn during spring, especially as the population of locally-nesting birds has increased—migrants passing through are gone from the state before planting season. Designating the crane a game species might be necessary now or in the future to manage their numbers, but that wasn't part of the DNR's rationale in changing their status, and they never held a fair and open hearing about it. Right now, there isn't any science to establish that the cranes hunted in the northwest region belong to a rapidly-expanding population. And even after several years of hunting, the DNR is still using the Sandhill Crane to encourage contributions to their Nongame Wildlife Program website. This is seriously wrong.

Now that we're living in a world where the federal government talks about alternative facts, I guess I shouldn't be surprised that one of our state's departments would develop an alternative definition for the word nongame. But we've lost something important. Since the Migratory Bird Treaty Act was passed a century ago, we've had a large body of true conservationists made up of hunters and non-hunters both, with two groups of extremists, anti-hunters on one side and on the other side, poachers and "canned hunt" advocates who hate limits and regulations. As some of the state's game species have become too rare to be easily hunted, the DNR seems now to be losing their focus on restoring those species in trouble, and instead is forcing an ugly wedge between hunting and non-hunting conservationists like me who have a long history of supporting and defending the tradition of hunting and its important role in conservation, whether or not we ourselves hunt.

Were the cynics right? Has the Nongame Wildlife Program been grabbing money from non-hunters to restore threatened species like cranes and wolves just so hunters could once again shoot them? If the Trumpeter Swan is designated a game species in the state after all the money, time, and effort non-hunting individuals and wildlife rehabbers put into restoring them and protecting them from the lead that hunters once spewed in wetlands and continue to spew in upland habitats, hunters will have squandered their reputation as conservationists. Is it time for our Minnesota Department of Natural Resources to change its name to the Minnesota Department of Game?