Part I: The Vague and Nebulous

|

| Big Pete Road in Port Wing |

I was born in Chicago and my family moved, before I was in elementary

school, to a town called Northlake in the western suburbs. A polluted creek ran

along the grounds of Automatic Electric, a huge factory built on what had been a golf course, and I took lots of

walks there, feeling like I was immersed “in nature.” Generic trees lined the

creek, and dandelions and a few nameless flowers poked through the lawn. Little

rodents we called gophers peeked out of holes. I had no idea that they were

13-lined ground squirrels, nor that the squirrels in my own backyard were of two

different species, gray and fox. I’d heard of chipmunks thanks to Disney’s Chip

‘n Dale, but had never seen a real one.

I knew three birds: the little sparrows

that begged for French fries at McDonald’s, the robins running on our lawn or

picked up dead for a day or two after the DDT truck went by, and cardinals that

sang in our maple tree. I didn’t know if any bird running on a lawn could be correctly

called a robin, or if any red bird was a cardinal, and didn’t know how to

recognize a maple tree except the one out my window—for all I knew, maple was

that tree’s name in the way that Laura was mine.

As a college freshman at the

University of Illinois, I was active in organizing our first Earth Day

celebration in 1970, but my understanding of the outdoors was little more

informed than the understanding of a baby whose unfocused eyes gaze in wonder

at kaleidoscope shapes and colors in a shopping mall.

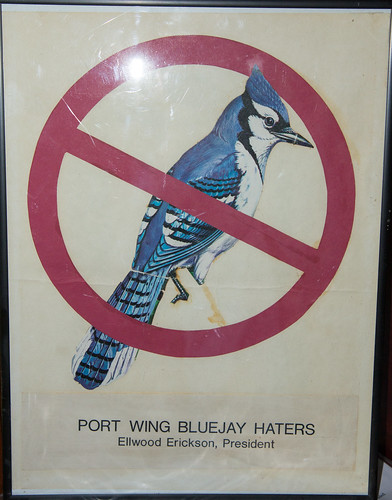

In 1973, before I took any college zoology classes or became

a birder, Russ and I visited his parents in rural Port Wing, where they were

fixing up a house for retirement. This was a far more natural place than any

I’d ever been to, but all I saw were more generic trees and flowers, and a lot

of mushrooms. I noticed an occasional robin, but no other birds.

|

| Broad-winged Hawk |

I’m not quite sure how I got through reading Walden in high school, much less getting

A’s in English. What meaning did I extract from sentences like "… the single

spruce stands hung with usnea lichens, and small hawks circulate above, and the

chickadee lisps amid the evergreens, and the partridge and rabbit skulk beneath”? Hawks were zoo birds, not anything you could see in the real world. Bald Eagles

and Red-tails and Broad-winged Hawks almost certainly flew right over my head

on that first trip to Port Wing, but I was blind to them. The various animal

and plant names Thoreau mentioned were thesaurus words—fancy terms you stuck in

your writing to sound smart and impress teachers.

|

| Barred Owl hooting |

I could certainly buy Thoreau’s line, “I rejoice that there

are owls”—I loved the one in Disney’s animated

Sleeping Beauty. But I was mystified with his next sentences:

Let them do the idiotic and maniacal hooting for men. It is a sound admirably

suited to swamps and twilight woods which no day illustrates, suggesting a vast

and undeveloped nature which men have not recognized. They represent the stark

twilight and unsatisfied thoughts which all have.

Now I realize that Thoreau was

talking about the Barred Owl, something clear to anyone who has heard a pair’s

bizarre courtship calls. Thoreau’s fancies were not fed by amorphously generic

nature—his imagination was sparked by the real—the particular—even if I didn’t

understand that.

I needed one small thing to shift my understanding and bring

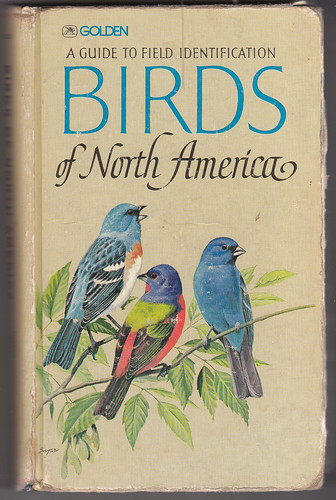

my nebulous concept of nature into focus. The field guide I received for

Christmas in 1974 became my personal catalog to the particular.

|

| My Golden guide |

Part II: Cataloguing the Particular

The Sears catalog of my youth gave specific names to household

objects. Everyone knew that dads wore shirts—the catalog gave me the words for particular

types of shirts—pinstripes or plaid, long-sleeved or short-sleeved, button down

or spread collars. People used pots and pans to cook, and the catalog gave the

correct names for each kind—frying pans, 1-quart saucepans, double boilers, kettles. Having particular names for them made me pay closer attention, and made even mundane household items more interesting.

For a Christmas gift in 1974, I received a field guide to

the birds, and the moment I opened its pages, birds were no longer mysteriously

generic things. My field guide catalogued the particular, making me both aware

of the myriad possibilities and interested in looking closely at every bird’s

every feature.

|

| Black-capped Chickadee |

When I identified my first bird, a chickadee, it was like

getting a delightful package I’d ordered from the Sears catalog, but also a

splash of cold water in the face. These chickadees had been in Baker Woodlot

all along, on every walk Russ and I took there. But until that moment, they’d

been invisible to me.

Now whenever I saw a bird, I paid attention to its

particular features. Soon I could instantly recognize chickadees, and by

scrutinizing the features of non-chickadees, I could find them in the field

guide. I’d been to Baker Woodlot at least a dozen times before I took up

birding, and birds were there every time. Now that I had a field guide,

suddenly I could see them.

|

| Mallards |

The ducks on the Red Cedar River on campus morphed into

Mallards, and now I could distinguish drakes from females, adding richness and

nuance to my concept of ducks; in that first year, I identified eight different

duck species swimming in the very spot in Chicago, along Lake Shore Drive,

where Russ and I had gone countless times to see sailboats, yet before, if I’d

noticed ducks at all, they were simply “ducks.” And before the year’s close, I saw

my lifer Snowy Owl flying low over a sidewalk along that stretch of Lake Shore Drive, it’s eyes

meeting mine. This new world of particular, cataloged birds was not just a rich

one—it was magical.

Catalogs show not just a bunch of items but also a price for

each one; my field guide used words like “common” and “rare,” general types of

habitat, and seasons of the year, along with range maps, to give me a general

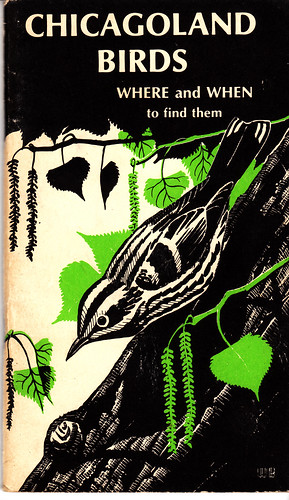

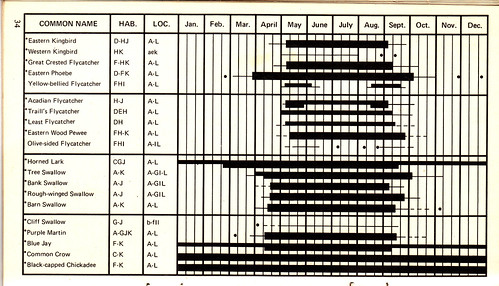

idea of how much I needed to invest to find each bird. I discovered a better

figurative price list a couple of weeks after I started birding, in a booklet,

“Chicagoland Birds: Where and When to Find Them.”

It said 372 species had been

recorded within 50 miles of the city, 200 occurring regularly, with 173

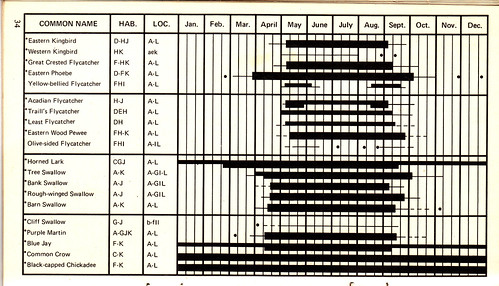

breeding there. For every fairly regular species, the booklet had a little graph

showing how common it might be in Chicago from month to month, and listed the

habitats and some specific hotspots where each could be found.

According to the

graphs, chickadees were easy year-round; Barn Swallows abundant only from

mid-April through mid-September, and nowhere to be found from November

through March. If a bird in the field guide struck my fancy, I could look it up

in my Chicagoland Birds book to see how likely it was that I could find it in

or near the city.

When I could get to a birding hot spot listed in the book, I

was guaranteed to see a bunch of birds, and even when I couldn’t, just walking

in our old neighborhood I was easily spotting Chimney Swifts and nighthawks,

juncos and White-throated Sparrows, Rose-breasted Grosbeaks and Baltimore Orioles on the same blocks where for the previous 23 years I’d noticed nothing

but House Sparrows, robins, and an occasional cardinal. How could I have missed

so very much for so very long?

Little by little, my love for each particular bird drew

particular plants into my sphere of understanding, too. To love Northern

Parulas, one must know and appreciate balsams draped with usnea lichens. To love Kirtland’s Warblers, one must love jack pines

and the fire cycles that regenerate the trees to ensure that stands of the

right size are always available for Kirtland’s nesting. To love goldfinches is

to love thistles despite their thorns. Knowing that a streamside thicket would

have Willow Flycatchers (well, "Traill's" back then) and Yellow Warblers while a beech-maple forest would

have Tufted Titmice and Great Crested Flycatchers made each forest ever so much

more than trees.

It would cost time and money to explore America in order to

see all the species catalogued between my field guide’s covers, but unlike the

products in a Sears catalog, the birds in my Golden field guide were priceless

in the literal as well as figurative sense. The best things in life really are

free, and my little field guide, which cost all of $4.95, was truly Golden.