|

*****

Right after my third baby was born, when I was still

recovering from a long labor and not quite back to myself, I received an

advertising postcard from a local plastic surgeon, whose name I have mercifully

forgotten, suggesting that this would be a perfect time for a facelift. As I

recall, the message had just a bit of an ominous tone about how marriages are

vulnerable during this time because of the toll pregnancy and childbirth take

on “gals.” This was one of those occasions when I considered the real value of

a 5-day waiting period before one can buy a handgun.

I’m very comfortable in my own skin, though I'm a rather shy person and have always been self-conscious. If I were a male songbird, I'd be like the chickadee singing from within the branches, so others could hear but not see me, rather than the mockingbird singing on the pinnacle of a tree and doing amazing loop-the-loops in flight, flaring out conspicuous wing patches as I sang to draw everyone's eyes as well as ears to myself.

Like most birds, I spend as little time around mirrors as possible, but haven't minded getting older. Indeed, I feel darned lucky to be 62 years old--my life has already lasted 12 years longer than my father's did, and 9 years longer than my little sister's. I’m perfectly comfortable doing radio, as long as no one is watching me do the recording—that’s why I was so motivated to learn to do my own sound editing when I started doing “For the Birds,” and why I started recording at home the moment I figured out how to do all my production work digitally. Back in the 1980s and early 90s when I’d be invited to speak in front of people, I often couldn’t get a single word out until the slide projector was on, the lights were out, and I was safely situated in the back of the room. It wasn't that I didn't like how I looked—I was just very self conscious about speaking in public. It would have taken way more than a mass-mailing postcard to get me to a plastic surgeon.

Like most birds, I spend as little time around mirrors as possible, but haven't minded getting older. Indeed, I feel darned lucky to be 62 years old--my life has already lasted 12 years longer than my father's did, and 9 years longer than my little sister's. I’m perfectly comfortable doing radio, as long as no one is watching me do the recording—that’s why I was so motivated to learn to do my own sound editing when I started doing “For the Birds,” and why I started recording at home the moment I figured out how to do all my production work digitally. Back in the 1980s and early 90s when I’d be invited to speak in front of people, I often couldn’t get a single word out until the slide projector was on, the lights were out, and I was safely situated in the back of the room. It wasn't that I didn't like how I looked—I was just very self conscious about speaking in public. It would have taken way more than a mass-mailing postcard to get me to a plastic surgeon.

I can understand why people whose

appearance is an essential part of their careers turn to surgery and Botox

procedures and such, but that hardly seems in order for me, and billboards, TV

commercials, and postcards on behalf of physicians designed to make people, perhaps especially post-partum women, feel inadequate and embarrassed about their

appearance seem both tawdry and unethical.

|

| The upper left bird is the fledgling, in perfect plumage. Dad or Mom is the bedraggled one who just gave the chick a mealworm. |

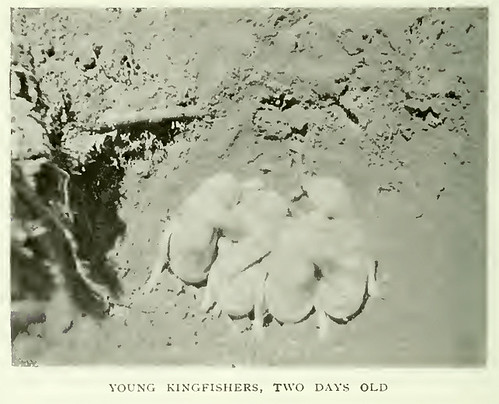

I always figured people would be happier if we were more

like birds. For example, a few summers ago, I took photos of a male chickadee

at the end of his season of raising babies. All parent chickadees look messed

up at that point, but he looked especially bedraggled—several people who saw

the photos thought he was at death’s door.

But ironically, the photo that seems

to show him at his very worst was taken while he was in full song, belting out his "Hey, sweetie!" without a trace of self consciousness, making sure his young all learned

exactly how a virile male chickadee is supposed to sound. Beauty is as beauty does,

and he would be in top form the following spring to raise a new batch of

healthy young.

I’ve been thinking about superficial beauty for the past few

weeks, since I had a speaking engagement in Rochester. A couple of people

approached me after my talk to tell me I should get a spot on my face checked

out. I’d already had my doctor check that very spot a few months ago, when it

looked more like rosacea than cancer, and I felt embarrassed that my talk

hadn’t been compelling enough to keep everyone’s attention on birds rather than

my face, but I figured I might as well go back to the doctor. She biopsied the

conspicuous spot and one hidden on my forehead, and sure enough, they’re both

basal cell carcinomas—the least dangerous form of skin cancer, but cancer

nonetheless.

So I was referred to the dermatology department at our

medical provider. When I called them, they put me on hold for about 15 minutes, and then when I did

get through, they could not connect me to the appointment desk and told me

they’d get back to me in “two to three weeks.”

When I do finally reach the appointment desk sometime before the Christmas Bird

Count, the appointment they finally set up will not take place until spring

migration kicks in. If only I’d wanted a facelift or Botox and didn’t depend on insurance, I’d be in and out quickly, assuming I survived, and soon people

could be ridiculing my face job as they feel free to do with any

self-conscious Hollywood actress who's had work done.

Imagine explaining cosmetic procedures to a chickadee, or

any other bird. Birds of both sexes tend to judge potential mates by age and

experience—the older and more experienced, the better. In species that have

physical changes indicating increasing age, potential mates are virtually always drawn to

the older, rather than the younger, bird because all those life experiences

point to success in the things that really matter. Waxwings grow more of those

red spots on their secondary wing feathers as they get older.

Accipiter hawks

develop a redder eye as they age.

Male chickadees work their way up the flock

hierarchy rather steadily as they grow older and more experienced, the feathers

on their cap and bib growing in increasingly black, and those on the cheek

whiter, showing off each bird’s age as a badge of honor, not something to cover

up with plastic surgery or dermatological procedures. As bedraggled as my male

looked at the end of his child-rearing responsibilities for the year, his

attractiveness to females was enhanced, not harmed.

The chickadee visiting my feeder last winter with the

deformed bill never did succeed in nesting this year—it was having enough

trouble obtaining and eating food for itself with such an elongated bill, and would

have had even more trouble feeding young.

I suspect it was old enough to have

had a mate before the deformity developed, considering that the moment I

offered it mealworms this winter it came instantly to my hand—I’d not put out

mealworms since before my Big Year, so this one had to have remembered me from early

in 2012.

Sometime in the spring, the bizarrely elongated tip of the upper bill broke

off, and now the bill looks almost normal, but that happened after the other

birds in the flock were all paired off. That particular chickadee is also

missing the three front toes on the right foot.

It seems that that may have

been a fairly recent injury, because the right side of its head often looked somewhat poorly groomed, and in the winter and spring it didn’t always seem to be

holding on securely to branches. Months later, it seems much steadier on its

feet and is better groomed, though I can still see a bit of difference on

its face, making it easy to pick out even when the feet aren’t visible.

It’ll

be interesting to learn whether its bill gets overgrown again this

winter, the time of year when deformed bills seem to appear most in feeder birds, and also whether

it will attract a mate. But if it can’t, that won’t be for

looking its age. For birds and sensible mammals, every day is a triumph, not something to hide with cosmetic surgery.

Meanwhile, as I wait rather impatiently for my turn to make the appointment for the procedure to remove the cancerous lesions on my face, I've been trying to figure out what the holdup is. According to an article in the Minneapolis Star Tribune from this February, there’s a huge shortage of dermatologists throughout the state.

Apparently the University of Minnesota’s medical school currently graduates

only about 5 new dermatologists a year, and more and more dermatologists are

spending more and more of their time on unnecessary cosmetic procedures. And more and more dermatologists insist on payments by cash or credit card—many no longer accept payment via insurance, even for patients with medical needs. What some doctors are calling “entrepreneurial medicine” is exactly what I

found so offensive when I got that postcard telling me I should get a facelift

30 years ago. These are the people preying on aging actors and insecure

people of all ages, and limiting their medical services to people wealthy enough to pay cash.

Thanks to the increase in cosmetic procedures and to

competition because of the shortage of practitioners, dermatologists as a whole

have seen a 50 percent increase in their incomes since 1995, while primary care

physicians’ incomes have grown only 10 percent. Meanwhile, the very

dermatologists who prioritize cash-paying cosmetic patients are blaming the

shortage of doctors dealing with skin cancer on Medicare cutbacks that leave

less money to fund the residency programs that produce more doctors, despite evidence that the current medical establishment intentionally limits the number of new doctors who would be competing with them. It’s

supremely ironic that the same so-called professionals who owe their lucrative

careers to the publicly financed residency system that trained them now defend the free

enterprise system, even as they whine that medicine needs more public financing

if we’re to have enough doctors. The entire system is poisoned.

As I said, basal cell carcinoma is the least dangerous

form of skin cancer, and I’m sure melanomas get much more prompt treatment. Even though the more conspicuous of my lesions grew very quickly and now I seem to be developing a third one, there's a pretty low probability that my cancers will spread far. Some

people say my wait is reasonable “triage.” Of course more urgent needs should

come before the least dangerous form of skin cancer. But meanwhile, if I’d

wanted a Botox treatment, or a face-lift, or breast augmentation or reduction, I’d be recovering now rather than seeing cancerous lesions every time I look in the mirror. How can anyone defend a system in which someone

frowning into a mirror at a few wrinkles gets top priority over that?

A few friends have suggested ways I could finagle my way higher up in line, but that doesn’t seem cricket—chickadees take turns and follow a regimented procedure for waiting in line at food sources, but are of the mindset that "we're all in this together," so no cutting in line for them. If the line waiting for essential dermatological care is too long, that’s not the fault of the people ahead of me—it’s the fault of a cancerous system that keeps the number of dermatologists so much lower than what we need at a time of ever-increasing skin cancers.

A few friends have suggested ways I could finagle my way higher up in line, but that doesn’t seem cricket—chickadees take turns and follow a regimented procedure for waiting in line at food sources, but are of the mindset that "we're all in this together," so no cutting in line for them. If the line waiting for essential dermatological care is too long, that’s not the fault of the people ahead of me—it’s the fault of a cancerous system that keeps the number of dermatologists so much lower than what we need at a time of ever-increasing skin cancers.

Every social species, from ants to chickadees, has important strategies to protect the social structure underpinning every individual's survival. Watching my own chickadees, I can easily see how even as the system rewards the fittest chickadees as individuals, every chickadee, from the highest to the lowest on the flock hierarchy, honors its flock's needs. Each chickadee squirrels away as much food as it can against future shortages, but if one chickadee's stores are wiped out, the others don't mind sharing their stores with it.

We like to tout the myth of the self-made man, when it is our society—our schools and infrastructure and the people who produce our food and clothing and other needs and services and pleasures—it's our whole flock that allows individuals to thrive. Sadly, the one scale on which we humans outstrip every other animal is our species’ amazing ability to rationalize greed and selfishness and cutting in line and stepping on others to claw our way to the top. Chickadees are far, far wiser. I'd rather be like them.

We like to tout the myth of the self-made man, when it is our society—our schools and infrastructure and the people who produce our food and clothing and other needs and services and pleasures—it's our whole flock that allows individuals to thrive. Sadly, the one scale on which we humans outstrip every other animal is our species’ amazing ability to rationalize greed and selfishness and cutting in line and stepping on others to claw our way to the top. Chickadees are far, far wiser. I'd rather be like them.

Please don’t comment that I need to be using sunblock. I’ve

been consistently using sunblock since I was in my 20s, and I haven’t gone out

without 50-SPF sunblock on my whole face and neck, plus a 30-SPF on top of that

on my nose and chin, plus a hat, since I was in my early 30s. Indeed, as a birder who has spent so very many hours outdoors over the years, in the tropics and the southern US and high on mountains as well as in my northern birding haunts, not getting any skin cancers at all until I reached my 60s is evidence that my precautions have served me well. But even if I

hadn’t been so conscientious, that kind of advice after the fact seems at best

hollow and uncaring.