|

| Helen and me at the Port Wing Fall Festival in 2014, when she was 95. |

Helen Erickson, my mother-in-law, who I’ve known since I was 16 years old and who gave me my very first pair of binoculars and field guide, died in the early morning on Saturday, December 8. She was 99.

I’ve long talked about how I got my start in birding when Russ and I were in college and he told his mom to give me my original birding equipment for Christmas. She had a small bird feeder in her suburban Chicago backyard, where I saw my very first junco and grew more familiar with some other common birds as I was starting birding.

On college breaks when Russ and I would visit Chicago, she often took me to various birding spots like the Morton Arboretum and the Little Red Schoolhouse Nature Center. One time when her car got stuck in a slurry of snow and ice on a wet, muddy road, she calmly turned the engine off, jumped out of the car, opened the trunk and took out first a small shovel, digging out some of the snow in front of the stuck tires, then took out some rag rugs and wedged them into position in front of the stuck tires, started the car again, and voila! Without saying a word, she was modeling how independent, self-sufficient women are prepared to deal with emergencies as they come, without losing their cool.

Thanks to that field guide and binoculars, I quickly became obsessed with birding. My skills and experience eventually surpassed hers in that one area, though neither of us felt any kind of competitiveness. Indeed, she took a great deal of pride in my birding and then in my radio program. One time when I was visiting her in Port Wing, she was helping a neighbor prepare for a luncheon. When we went to her house to bring over what Helen had prepared, she had me carry in the cookies while she carried another armload. Her friend exclaimed when she saw the cookies, “Oh, these look wonderful! Did you bake them, Laura?” Before I could even begin a response, Helen jumped in with, “Laura doesn’t have time to sit around baking cookies! She has much more important things to do with her life.” She must have talked about my birding to her many friends, because they would send her clippings from all over of news stories related to birds, writing on them, “For Laura.”

She took enormous pride in “For the Birds,” and was my most loyal radio listener—if KUMD was even a minute late airing it, she’d call the station asking “Where’s Laura today?”

In January 2009, we held a 90th birthday party for Helen in Port Wing. The whole town was there, and we heard lovely stories about her. She was still going along on local nature hikes, easily keeping up with people half a century younger, noticing and identifying all kinds of things that would otherwise have gone unobserved. It was lovely to hear all the stories.

But she was growing more forgetful, our first intimation that dementia was setting in. She was also getting a bit frailer. She was still quite independent and capable of living on her own, more than half a mile from her nearest neighbor in rural Port Wing, until 2012, when she was 93 and developed a crippling case of bursitis. I spent much of that year living 24/7 with her.

That’s when I was writing the

National Geographic Pocket Guide to Birds of North America, and she got a huge kick out of it whenever Jonathan Alderfer, who edited all of National Geographic's bird books for decades, called so we could hammer out various issues, from selecting the species to be covered to choosing the artwork. The sad thing was that every time I took one of these calls, Helen had forgotten that I was working on a National Geographic book—but each time she found out, it made her excited and happy all over again.

While I was staying with her that year in May, Ryan Brady, Dick Verch, and I did a Big Day, starting out at Ryan's place in Washburn. I headed there the night before after Helen and I had dinner, so we could start birding around 3 am. I’d arranged with some of Helen’s friends to come by with Helen’s mail and to check on her—I didn’t get back until 10 pm. I thought she’d be getting ready for bed, but she had waited up for me, and immediately started to fix me dinner while asking me all about the day’s birding.

She was still so competent in so many ways, and the bursitis cleared up, but her dementia was making driving dangerous and her general confusion was leading to other serious problems, so by December 2012, we were all growing to realize that she couldn’t manage on her own anymore. It was also becoming increasingly difficult for Russ and me to go back and forth so often, so we finally decided that the best thing would be for her to move in with us.

That changed our home routine quite a bit, but was easy to adapt to, and it was lovely having her with us. She was always self-sufficient, and kept herself busy by day, but I started spending my evenings watching movies or TV shows with her. She was receiving eldercare at our health care provider, and they gave us a set of exercises that would help maintain her strength and preserve her ability to balance for as long as possible. I did those with her every afternoon.

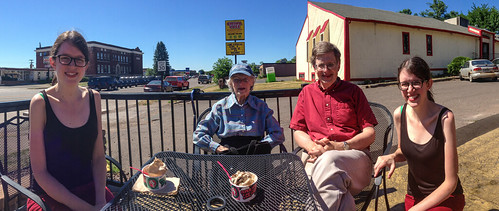

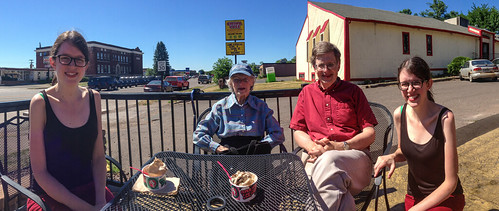

|

| I took this photo in 2013, using my iPhone's panorama function. Helen got a huge kick out of how it turned out--Katie had jumped up after the camera passed her on one side and ran behind me to get back in by the time the camera panned to the end. |

For the first three and a half years, I drove her to and from Port Wing every two weeks for card club, one of her most treasured routines. It was win-win for me—not only was I being a dutiful daughter-in-law, but I got to spend a couple of hours every two weeks birding in my beloved Port Wing. For the first couple of years, we had lovely chats on our drive—I’d point out birds, we’d both spot deer and an occasional raccoon or even bear along the road, and we’d reminisce or chat about random things. I made up a playlist of songs I knew she liked for our drives, and every now and then one would trigger a memory for her; the stories she told made this shared time even more precious for me.

But as her dementia progressed, she was also growing increasingly detached from friends, family, and everything else, and was also having more trouble keeping track of the cards and scoring. And the long drive had been becoming more uncomfortable for her, too. So finally her visits to Port Wing came to an end. The last time we brought her to the Port Wing Fall Festival was in 2015, when she was 96.

|

| Helen, Russ, and Pip at the Port Wing Fall Festival in 2015. |

When Joey or Katie were in town, we’d pull out our Uno cards and all play, and Helen was still winning as often as anyone else.

|

| Helen playing cards with Joey and Katie long, long ago, when Tommy was still too little. |

She and I were still enjoying movies and TV shows in the evening, too. But little by little, she was losing pleasure in the things she’d once loved. When she was standing in the kitchen or near the dining room window and I pointed out a Pileated Woodpecker at the feeder, now she wouldn’t even look up.

Helen collapsed while standing in the kitchen this past May, and broke her leg at the hip. Surgery went well, but she developed edema, and the pain in her leg didn’t go away. Russ patiently did exercises with her every day trying to rebuild strength in her legs, because the hallways and doors in our very old house are just too narrow to accommodate anything wider than a narrow walker—the nice wheeled walker we’d gotten for her couldn’t negotiate turns here, and no way would a wheelchair work here. So when Medicare rules cut her off from rehab when she didn’t improve quick enough, she had to stay in the nursing home.

A couple of months ago, I could tell she no longer recognized me most of the time, but she’d still brighten up when I brought my little dog Pip in. I got Pip groomed last Monday, and she was at her most adorable, wearing a Christmas neckerchief and bow—the kind of adornments Helen always loved.

But when I brought her to the nursing home, Helen didn’t smile or seem the least bit interested. Little by little she’d been slipping the surly bonds of earth. On Friday, my sister-in-law Jean came in from Chicago.

|

| Helen, her daughter Jeanie, and her son-in-law Mike |

Helen did recognize her, and was still recognizing Russ, her two children. They kissed her goodnight and left at Helen’s regular bedtime. And after such a very long farewell to all of us who loved her, and after making her final goodnight to her beloved children, Helen went to sleep for good.

|

| Helen receiving birthday greetings on her 99th birthday this January 24. |