Last summer, the Princeton University Press released a book

by Tom Stephenson and Scott Whittle, The

Warbler Guide. When I first read about it, I admit I rolled my eyes

thinking, “Not another one!” My library already included four field guides

specifically about warblers. They’re all good in one way or another, but I don’t

usually consider field guides to families to be useful, especially for

beginners, because they don’t show similar but unrelated birds that can be

confusing. (The great comprehensive guides to families are a different story.) The

Peterson guide to warblers is wonderfully comprehensive, but even that one is

worthless in the field when someone is starting out and isn’t sure whether a

particular bird is a flycatcher, vireo, kinglet, or warbler. But it’s very true

that birders of all levels are drawn to warblers, and anything that makes

identifying them easier is a Good Thing, and the publishers sent me a free

copy, so I opened it. And WHOA! The

Warbler Guide is a game changer.

The 137-page section that starts the book is a brilliant

tutorial in the basics of warbler identification—both by sight and sound—using

a methodical, objective approach that would benefit anyone studying any group

of birds. It so thoroughly covers identification both by appearance and

vocalizations that I want to highlight the two sections separately.

Warbler Appearance

In their “Topographic Tour,” Stephenson and Whittle use

brilliant colors to outline different feather groups and body parts within a

nice color photo, rather than using a simple line to point out the general area

of what could be a large or small structure not so easy for beginners to figure

out. David Sibley in his Birding Basics used

black-and-white line drawings, and Kenn Kaufman in his Advanced Guide to Birding brought it to the next level with black

and white outlines next to actual photos to show the particular feather groups

and body parts, but Stephenson and Whittle bring this clear-minded approach to

the next level.

The 40-page section on things to pay attention to when

looking at warblers is rich in photos showing each feature on different species

and, where pertinent, on similar non-warblers. Bill shape and length, eye

rings, eye lines, length of the tail and how relatively long or short the

undertail coverts are—all these features and more are thoroughly covered, and

reading this section will make anyone more able to discern a bird’s important

features. The section is rich with photos clearly comparing and contrasting

each feature on different warblers and non-warblers. There is also a section on

aging and sexing warblers—and the authors show how this is fairly

straightforward with some species but virtually or completely impossible with

others. They use wonderful drawings by Catherine Hamilton to illustrate points

more clearly understood and compared with drawings than photos.

There are also nine two-page spreads called visual finders.

These pages are an absolute treasure, and are, amazingly, all available as free PDF downloads on The Warbler Guide website, though I personally wish the publishers would also sell eastern and western versions as laminated, folded guides. These visual finders show all the species together so you can make a quick guess before thumbing through the species pages. One shows all the warbler faces in profile, another the whole body in profile, a third the side profile from a 45-degree angle, when we see more of the underside and less of the upper body, and a fourth from directly beneath. They repeat the full body profile views with another 2-page spread limited to eastern species in spring, another for them in fall, and have a single 2-page quick finder for western species. Finally, they use Catherine Hamilton’s drawings to compare close-up views of the under-tails of every eastern and every western species.

These pages are an absolute treasure, and are, amazingly, all available as free PDF downloads on The Warbler Guide website, though I personally wish the publishers would also sell eastern and western versions as laminated, folded guides. These visual finders show all the species together so you can make a quick guess before thumbing through the species pages. One shows all the warbler faces in profile, another the whole body in profile, a third the side profile from a 45-degree angle, when we see more of the underside and less of the upper body, and a fourth from directly beneath. They repeat the full body profile views with another 2-page spread limited to eastern species in spring, another for them in fall, and have a single 2-page quick finder for western species. Finally, they use Catherine Hamilton’s drawings to compare close-up views of the under-tails of every eastern and every western species.

Of course, the meat of the book is in the 354-pages of

species accounts. These include a wide array of photos of each bird with

comparison photos of similar-appearing species, listing all the bird’s features

and highlighting with a check the features that in and of themselves are

diagnostic. For example, if all you can see on a warbler hidden by foliage is a

bit of its undertail, but notice black “arrowhead” markings on a white

background, you for certain are looking at a Black-and-white. Some

straightforward warblers, such as the Black-and-white, are covered in 6-pages,

while those with more plumages or which can be easily confused with others,

such as the Blackpoll, can have as many as 10, and the Yellow-rumped, which has

different plumages for eastern and western forms, is covered in 12 pages.

The Warbler Guide is the perfect book for learning warbler plumages—stunningly beautiful, and fun as well as instructive. And it goes above and beyond that, with the most comprehensive coverage of warbler sounds I’ve ever seen.

The Warbler Guide is the perfect book for learning warbler plumages—stunningly beautiful, and fun as well as instructive. And it goes above and beyond that, with the most comprehensive coverage of warbler sounds I’ve ever seen.

Vocalizations

I absolutely love The Warbler Guide's thorough coverage of visual identification. But the book is a game

changer in another way, too, providing the best tutorial in learning bird songs

and calls I’ve ever seen, with liberal use of spectrographs of sounds, called

sonagrams, throughout.

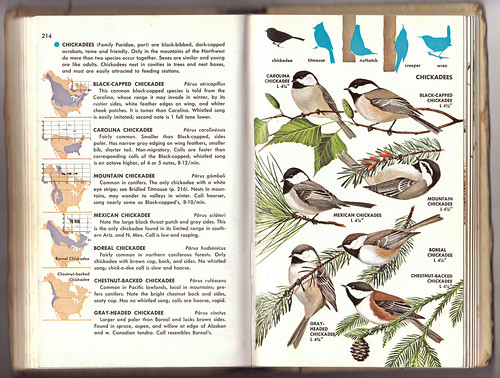

Many people find these graphs of sound scary and confusing. My trusty Golden Guide, the field guide I used in the 1970s when I started birding, is the only field guide I’ve ever seen that uses sonagrams.

I suspect that the reluctance of people to figure them out kept other field guide authors from using them. I intuitively grasped many of the concepts of sonagrams from the start, because I can read music, but it would have been enormously helpful for me when I was starting out to have read The Warbler Guide’s 38-page tutorial, and also to have been able to see a lot of sonagrams for each species, to better grasp the many different songs a single species can produce. This tutorial explains how to go about learning warbler songs, interpreting the sonagrams while listening to the exact corresponding sound via “The Warbler Guide Song and Call Companion,” available as a download for $5.99 via thewarblerguide.com.

Many people find these graphs of sound scary and confusing. My trusty Golden Guide, the field guide I used in the 1970s when I started birding, is the only field guide I’ve ever seen that uses sonagrams.

|

I suspect that the reluctance of people to figure them out kept other field guide authors from using them. I intuitively grasped many of the concepts of sonagrams from the start, because I can read music, but it would have been enormously helpful for me when I was starting out to have read The Warbler Guide’s 38-page tutorial, and also to have been able to see a lot of sonagrams for each species, to better grasp the many different songs a single species can produce. This tutorial explains how to go about learning warbler songs, interpreting the sonagrams while listening to the exact corresponding sound via “The Warbler Guide Song and Call Companion,” available as a download for $5.99 via thewarblerguide.com.

I

downloaded the Companion, which has over 1,000 short sound files, and set it up

in iTunes to play each sound on repeat until I advanced it manually to the next

sound. Then I read the introductory section about learning warbler sounds while

sitting at my computer with iTunes open. This was the perfect way to get a

visceral appreciation of how to interpret the spectrographs of bird sounds, and

to get a far clearer, more objective understanding of what to listen for while

identifying bird sounds than what field guides traditionally show. Even if you

can’t afford the $30 Warbler Guide, I

strongly recommend checking it out of a library, paying the $6 to download the

songs, and doing that tutorial. Learning what to listen for on warbler songs

will make distinguishing the songs of other families much easier, too.

After the basic tutorial on how to listen to warblers comes

what the authors call their “Song Finder,” in which they group the sonagrams of

similar sounds together, so you can see the spectrographs and read their clear

explanations of the differences while you listen to the sounds.

After you’ve gone through that amazingly in-depth but

enjoyable tutorial, you can head straight to the individual species accounts.

Just as The Warbler Guide provides

visual comparisons for each bird, it provides sounds, too. The song treatment

is extraordinary, covering the different types of songs, call notes, and

nocturnal flight sounds for that species along with similar-sounding

vocalizations from other species—again, downloading that sound download

provides extraordinary in-depth coverage for each species. I would not

recommend trying to read and listen to the entire Warbler Guide: after the initial tutorial, I’d prioritize the

species by which you want to learn first.

I got a free review copy last year, but love the book so

much that I paid for a second copy when the authors were at the popular Ohio

birding festival, The Biggest Week in American Birding, this year, so I could get

it autographed.

Most of the early fall warblers have passed through the

north woods now, though as of September 15, there is still a good variety out

there. This would be an excellent time to start reading The Warbler Guide and listening to the companion guide while you

get more comfortable identifying Palms, Yellow-rumped, and whatever others are

still hanging out. And spend a rainy afternoon or evening on that tutorial at

the beginning. Then keep thumbing through those species accounts now and then throughout

the winter, and by next spring, you’ll be identifying warblers like a pro. You’ll

be so glad you did!

THE WARBLER GUIDE

Tom Stephenson & Scott Whittle

Drawings by Catherine Hamilton

Paper Flexibound | $29.95 / £19.95 | ISBN: 9780691154824

560 pp. | 6 x 8 1/2 | 1,000+ color illus. 50 maps.

eBook | ISBN: 9781400846863 (Available July 7, 2013)

Pub date: July 24, 2013

Drawings by Catherine Hamilton

Paper Flexibound | $29.95 / £19.95 | ISBN: 9780691154824

560 pp. | 6 x 8 1/2 | 1,000+ color illus. 50 maps.

eBook | ISBN: 9781400846863 (Available July 7, 2013)

Pub date: July 24, 2013

Also, what sounds like a great app for The Warbler Guide will be

coming out in time for Christmas. I can’t wait to see it!

Picky Picky Picky

Most of the warbler photos in The Warbler Guide were shot with flash. Based on my observations of

my education owl Archimedes when people take his picture in various lighting

situations, and on my observations of songbirds at various birding destinations

when photographers use flash, I don’t think flash bothers birds much, or even

at all, in daylight. But the bright dot or weird reflections in the birds’ pupils

on some of the photos did bother my aesthetic sensibilities. The most egregious

case was their photo used to illustrate a Canada Warbler’s eye ring. The weird

and large white reflection in the pupil could confuse beginners about what and where

the eye ring is—I wish they’d photoshopped that out. The Canada Warbler photo

they use to illustrate its bill size and shape would have been a better choice

for showing the eye ring. The fact that this is the only thing about this

entire wonderful guide that I take issue with is pretty darned impressive.