(This is not at all about birding [well, except maybe to explain why I take so much solace from birds], and I don't usually reveal much about my childhood. But in light of the news, it's time I did.)

|

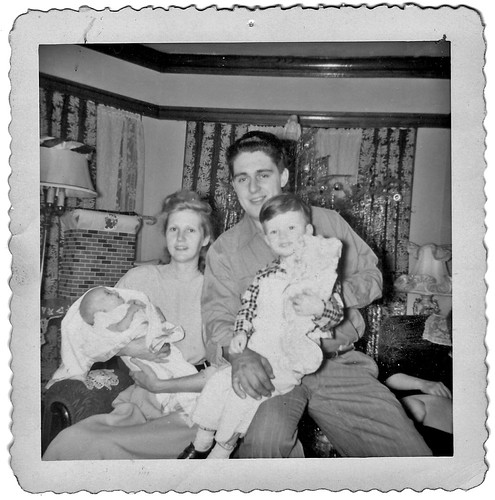

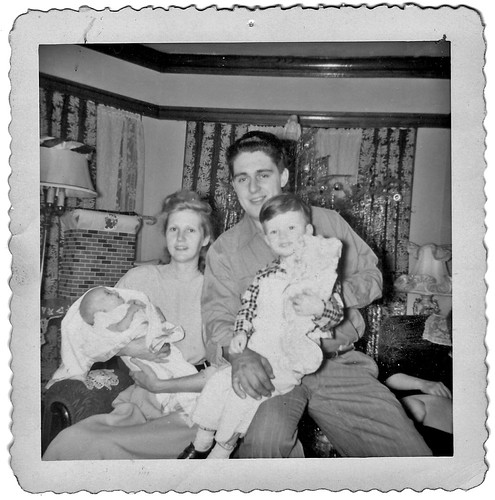

| My dad, mom, older brother, and me |

I loved my father. That’s important to stipulate from the

very start. I have fond memories of him singing “Popeye the Sailor Man” to us, barbecuing

chicken for summer picnics, and cooking corned beef and cabbage every year at my grandpa’s birthday party. We were the only kids I knew whose dad was a Chicago

firefighter and, for a time, a volunteer firefighter in our blue-collar suburb,

Northlake. That was our family’s claim to fame, and we were very proud of it.

|

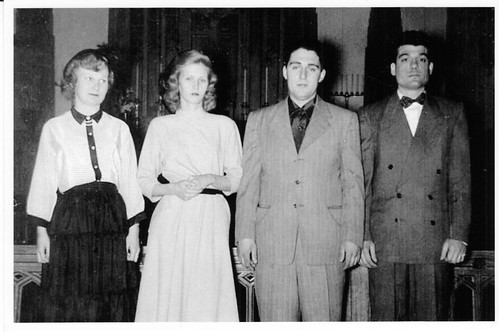

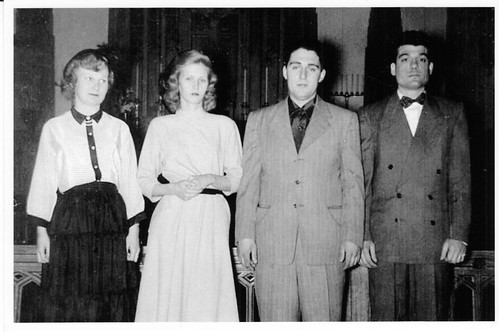

My dad and mother, flanked by my aunt and uncle, when my parents got married in 1949.

My mother was 17, my dad 19. |

My first memory of my dad is a sad one that maybe gives some

insight into why I loved and even felt protective of him, and made excuses for him in my heart. I must have been very

little, and my dad very young, because we still lived in our two-flat apartment

in Chicago—we moved away when I was four and he was 26. He came home from work one

morning (the fire department’s 24-hour shifts started and ended at 8 am). This

was the only time I can ever remember him coming home covered with soot and

smelling smoky—he’d usually take a shower at the fire hall before he left. I was

in the kitchen with my mother, who was standing at the sink with her back to

the rest of the room, and he walked in as if in a daze, picked me up ever so

gently, sat down with me on his lap, and started rocking and crying, his body

heaving with sobs. The tears ran down his sooty face in glistening streaks.

He started talking about the fire, and how a woman in the

street was screaming “My babies! My babies!” over and over, and how he and his

partner searched everywhere, and finally found the two little children huddled,

dead, in a closet. He did artificial respiration, but “We couldn’t make them

come alive again.” He buried his face in my hair. By then, I was crying, too.

My mother turned from the sink to face him and said coldly, “If you’re going to

do a man’s job, you damned well better grow up and be a man, you motherless

bastard.” He kissed me tenderly on the top of my head, softly put me down, and

walked out.

So for understandable reasons, my dad wasn’t around much

after that. Even during the periods when he and my mother were married and sort

of getting along, his 24-hour shifts as a Chicago firefighter kept him away one

out of every three nights, and he was often gone on other nights as well—he’d explain

that he’d had to work someone else’s shift. He got my mother pregnant six times

in eight years, but the fact that none of us had fall birthdays bore testament

to the fact that he missed a lot of Christmases. Back then the firemen each

were assigned a number from one to three, and the big fire department calendar

on our kitchen wall showed which were work days for his number, but when he was

supposed to have Christmas off, he’d tell us about some poor fireman whose

children needed their daddy on

Christmas, so he’d traded days with him. I’d try to feel compassion for those

poor children, never, at the time, thinking that maybe five little Farleys

needed their own daddy on Christmas, or that maybe he was not really working on those days. I also tried not to think about how he was

leaving us pretty much defenseless with my mother. When that did occur to me, I justified it, because what could he do?

Truth to tell, things were a bit more peaceful when he

wasn’t around. We had developed strategies for appeasing my mother's rage or at least diverting

her attention, but when he showed up, all bets were off. Our strategies weren’t 100 percent effective—I wore tights and long sleeves

to school even on hot days to cover the welts and bruises. Like most children

in this situation, I was ashamed, knowing if anyone saw them they’d know what a

bad little girl I must be.

My mother’s constant bitterness and unpredictable rages pervaded our every waking

moment and seeped into our dreams, so I usually felt more sympathy for my dad than for her. And I could muster that sympathy for him, on and off, as long as he lived.

But I remember the exact moment, and the exact place, when I learned that my

father was a bad human being. I still loved him—what was my alternative? But just as had happened with my mother years before, I suddenly could see my father through clearer, more objective eyes, and things

were never the same again.

I may remember the moment, but I don’t remember exactly what year this happened. It was one of

the only times my dad was around when my mother wasn’t, and it happened after

we moved to Northlake, so I’m pretty sure it was while she was in the hospital

after her miscarriage in 1956 or 57, when I was four or five. My dad had to do some grocery

shopping at Dominick’s, and either left the other kids alone—my parents often

left all five of us on our own—or my grandpa or uncle was there helping and

didn’t think he could manage all five of us by himself. I was too old to ride

in the shopping cart, and my dad didn’t want me to slow him down, so he brought

me to the cereal aisle and told me to stay put and not move a muscle until he

came back.

The store wasn’t busy, so there wasn’t much to look at

besides cereal boxes, but they were colorful and cheery. Kix. Cheerios. Sugar

Smacks. Rice Krispies. Corn Flakes. Eventually a shopping cart turned into the

aisle. The first thing I saw was the little toddler inside—she was laughing and

clapping, but what arrested my attention was her hair. It was dark brown like

mine, and tied up in what looked like hundreds of little pigtails (looking back,

I’d say at least a dozen) each lovingly tied in a pretty pink bow. Her daddy

was pushing the shopping cart, and he pulled it up right by me, next to the

Cheerios. That’s when I saw her face—she had the biggest, happiest smile I’d

ever seen on anybody except on TV. She was having more fun than I’d ever dreamed a little girl could

have with her daddy, at least in real life.

He reached down and pulled her out of the cart, holding her

up to the cereal boxes that seemed almost as big as her, and told her to help

him pick one. She opened her pudgy arms wide and pulled out a box of Cheerios.

He wheeled her around so she could drop it into the basket as they both laughed.

As he tenderly placed her back in the little seat in the cart, he noticed me watching them, looked right into my eyes, and gave me a warm, friendly smile, his eyes crinkling. For one beautiful moment, perhaps the most

perfect moment of my entire childhood, I felt drawn in and included—a part of that

happy little family.

The next moment everything shifted horribly. He started pushing the shopping cart away, straight toward where my father was turning into the

aisle, facing them directly.

In the Little Golden Book, Sleeping Beauty, when the evil Maleficent shows up at the

christening, “the room darkened suddenly. A chill wind swept through it. And a

shudder passed over the crowd.” My grandpa gave me that book a couple of years

later, and when I read those words, the memory of that moment flooded my mind. The instant he saw that man and his little daughter,

my father's eyes filled with fury and naked hatred, and every bit of joy and cheer

drained from the man’s face. Instantly, it was filled with fear and a

kind of impotent anger that bewildered and frightened me. I was horrified to realize my father wielded a profoundly unfair power over this stranger. He wheeled

the cart around in retreat as my father charged forward, sputtering too, too

audibly, “It’s bad enough the niggers took over the city. Now they’re invading

the suburbs.”

Like a lightning bolt, I was struck with a shocking realization. Those horror stories my father came home from work telling us about, using

that ugly word over and over, weren’t about faceless, monstrous bogymen—he’d

been talking about this warm, friendly man, and this tiny child, and people just like them!

I couldn’t see the little girl in the shopping cart or the man’s face

now—just his rapidly retreating figure from behind. As he turned the cart around the corner

at the end of the aisle, I saw the child crying. I wanted so badly to catch

their eyes—to somehow convey to them that I wasn’t like that—I was nice—please

take me home with you, far, far away from ugly cruelty and

mean-spiritedness. Please.

Five years old is too young for children to face

the harsh truth that their father can be horrifyingly, cruelly, absolutely

wrong about something so important. I suppose it was easier for me to accept,

having learned that same lesson about my mother at an even younger age.

My whole life, I’ve been haunted by memories of this brief

encounter. I often wonder what became of that man and his little girl. She was

so little—only about two or three. Could she have forgotten all about it? Did she carry

away a vague, inchoate sense of dark menace lurking all about that could pop

up anywhere? Could a box of Cheerios trigger bad memories? Did she grow up

scared of every white man? Did her daddy teach her to not be prejudiced—to

understand that not every white person was like that? How would she know which

was which? She’d be in her late fifties now—sixty-one at the oldest. How has she

negotiated this world in which we pretend as much as we can that racism is

dead, that the bad white people, even the ones in positions of power, are mere

outliers? Does she have children? Grandchildren? Can she sleep at night before

they’re all accounted for?

And what about her daddy? Did he encounter other people like

my father—people who hated him for simply being? My father’s temper and

lack of filters may have made him something of an outlier, but I knew plenty of

grownups who shared his attitudes. Did the man in the grocery store

develop some kind of radar to anticipate ugly encounters before they happened?

Even if he somehow developed thick enough skin to deal with bizarre and random

attacks on himself with equanimity, how infuriating it must have been to not be

able to protect his tiny daughter from such ugliness. How did he deal with that

anger?

And what about me? I have always been haunted by a vague but pressing feeling that I owe

these two people a heavy debt impossible to pay. I feel complicit, by virtue of

blood, by virtue of my inability to change my own father’s mind and heart, and by

virtue of living in a system that protected me from that kind of horrible

encounter thanks to nothing more than my skin color. Never once have I entered

a grocery store, or any other place, and been viciously assaulted with ugly

words just for being there.

Are the sins of the father visited upon the children, and

upon the children's children, unto the third and to the fourth generation?

Every

time I read yet another news story about a hot-headed white man murdering

yet another black child, I can’t help but think of my dad. On this Father’s Day

weekend, so soon after a 21-year-old terrorist gunned down nine people

in their church, my response to the news is filtered through memories of him.

We—family and

friends, society at large—every one of us is personally responsible for reining in that kind of hatred

long before innocent people are killed; long before it can even erupt in ugly

words shot like bullets at innocents in a grocery store. Some people,

virtually all white, feel a magical distance between themselves and racial

tension. Of course they’re not

racists! This wasn’t their fault!

When they listen to Rush Limbaugh spewing hatred or NRA spokesmen disingenuously

saying the victims should have been armed; when they defend the tradition of the Confederate flag, that

treasured symbol embraced by the Ku Klux Klan, I can’t help but think of the Prince saying "See what a scourge is laid upon your hate," as he gazed upon the young bodies of Romeo, Juliet, and Tybalt. He had tolerated the strife between the two families, not intervening to stop the hateful exchanges, and now was wracked with guilt for his complicity. “And I, for winking at your discords, too, Have lost a

brace of kinsmen. All are punished.”

I think of the words of Thomas Jefferson:

Deep rooted prejudices entertained

by the whites; ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they

have sustained; new provocations; the real distinctions which nature has made;

and many other circumstances, will divide us into parties, and produce

convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one

or the other race.

Is Jefferson’s bleak forecast the only way this can end, or

simply the only way he could imagine two centuries ago? He could not envision the many messages

of peace from Martin Luther King in the ‘60s, or the gentle forgiveness bestowed

on the murderous Dylann Roof by so many grieving members of the families of his

victims on this sorrowful Father's Day weekend. But as long as we white people live in complacency, even as

our society is diminished by the losses of so many innocent compatriots, I fear

for worse to come, those memories of my father’s hatred so vividly flashing through my mind.

He had a hair-trigger temper. Several times we kids were

along in the car on the Illinois Tollway when, incited by some perceived

transgression by the driver ahead of him, he’d speed up to “tap” the guy’s rear

bumper, over and over. My mother and siblings would laugh—either thinking

that playing bumper cars at 80 mph was funny or as an involuntary response to

fear—as he lowered his head at the wheel, a raging bull muttering obscenities

and roaring the engine. After he’d forced the car over to the shoulder, he’d

yell a victorious whoop as he sped past, giving the hapless driver the finger, and

it would take an hour or more before he cooled down. He made the newspaper in 1965 when he punched a judge during the hearings for his

divorce from his second wife. And when he became an ambulance driver for the

fire department, he often came home boasting of leaving someone “bleeding on

the street” after they “mouthed off” to him or his partner—“those people” had

to “show some respect.”

The NRA today targets their message at people exactly like him.

They fan the flames of paranoia and hatred to ensure that more and more gun

purchases enrich the corporate manufacturers they represent. They weren’t like

this in the 50s and 60s—back then they were a true membership organization focused primarily on sportsmen. My father, like most city

people who weren't hunters of that time, never owned a gun. So I can console myself with this: at least my

father never outright murdered anyone. If he were a young man today, he’d be

armed to the hilt.

I argued a lot with him, about racism and other topics, as I

got older, but little by little I gave up, resigned to hopelessness. When I

started my first teaching job in Madison, Wisconsin, my father asked if I had

any niggers in my class. I was so stunned by the audacious obscenity of the question that

all I could blurt out was an indignant “No.” When he later saw photos of my beloved

students displayed in our apartment, he said, “I thought you said you didn’t

have any niggers in your class.” I looked him dead in the eye and said, “I

don’t.” He looked uncomfortable—I hope I made him feel ashamed, but I’ll never know. That was the last time I saw him alive.

He died when he was fifty from a massive heart attack. I cried and

cried, mourning for all he couldn’t be rather than for all he was, and filled

with grief about the debt I would never be able to repay to people I would

never be able to find, and to the many people just like them who were victimized

by an ugliness that is an undeniable part of my family heritage, a dark stain that will not wash clean.

My own first child was born a year after my father's death. If we are to honor all the happy traditions of our families with joy and share them with our children, each one who started out as a baby and toddler just like that sweet little one in the grocery store, mustn't we first acknowledge and sweep out the dark corners of that family heritage? Or will our children's children, unto the third and to the fourth generation, be born into a world still infected by this evil hatred? What are we, as individuals and as a people, prepared to do?

So on this Father’s Day, as I read so many loving messages

from friends about their fathers and the valuable lessons they learned from them,

I’m finally writing about my own father.

I loved him, and I learned valuable lessons from him. May God have mercy

on his soul, and on mine.