[Thanks to Ian Paulsen for a few corrections.]

At the start of 1983, birders had four choices for field guides. The best two were the Peterson guide, written by Roger Tory Peterson, and the Golden Guide, written mainly by Chandler Robbins.

The Golden Guide was getting dated. It was originally published in 1966, and the second edition, which came out in 1983 with a blue instead of tan cover, had a more pleasing typeface, was somewhat expanded and revised, with completely revised range maps, newly added western Alaskan species such as Eye-browed (now Eyebrowed) and Dusky Thrushes, and showing updated changes in bird names, but otherwise was very similar—almost identical—to the first edition.

Peterson had released the fourth edition of his field guide in 1980, finally adding some of the features that had made the Golden Guide so beloved from the start. Now all Peterson's birds were illustrated in full color with the illustrations facing the text. But most of Peterson's birds were still illustrated in a patternistic cookie cutter posture, which can be somewhat useful for comparing some plumage features but doesn't show the birds as we usually see them. Also, the newer Peterson guide kept the range maps separate from drawings and text, and still covered just the eastern or western half of the continent. So I still much preferred my beloved Golden Guide. It covered the whole continent, showed the maps on the same page with the text, and had an innovation that very few people appreciated at the time, sonograms—pictorial versions of the spectrograms that show a song’s frequency over time. Also, the Golden Guide’s illustrations by Arthur Singer showed the birds in more natural poses, often in characteristic vegetation that helped suggest habitat, and often with smaller drawings of the birds performing important behaviors, such as grouse displays.

(The third choice, the Audubon Society Field Guide, which had come out in 1977, was the first field guide to use photographs rather than drawings. It had so many drawbacks connected to layout, design, and organization that it simply wasn’t usable in the field, though I couldn’t help but notice it on the shelf in Julia Child’s kitchen in the exhibit at the Smithsonian. The fourth choice, the Audubon Society Master Guide to Birding, brand new in 1983, was a three-volume photographic set, much too unwieldy for the field.)

The game changer in 1983 was the publication of the first edition of the National Geographic Society’s Field Guide to the Birds of North America. Except for sonograms, this guide had everything that the Golden Guide had, with the added advantages of updated information, including changed bird names and more information about identification subtleties. The artwork wasn’t quite consistent—thirteen artists did the plates and three other artists contributed—but from the moment it was released, it was the best field guide available.

|

I have a copy of each edition in my library. I don’t think National Geographic’s aim was focused on field guide collectors, though—I think they have simply set a goal of providing the most complete, up-to-date field guide available, and that requires updates as our knowledge grows and as ornithologists tweak bird classification.

Other excellent field guides have entered the market since National Geographic’s first edition. My favorites are the Sibley Guide to Birds, first published in 2000, with the second edition in 2014, and Kenn Kaufman’s Focus Guide: Birds of North America published in 2000 and updated in a new printing and retitled the Kaufman Field Guide to Birds of North America in 2005.

Kenn Kaufman’s is the guide I recommend when people want an all-inclusive and portable photographic guide—it’s especially kid friendly. The Sibley guide is an indispensable reference, though way too heavy for me to have lugged in the field even when I was young and spry. He provides the most illustrations per species, but that means he can’t show as many species per page, making comparisons trickier. Since David Sibley does all his own artwork, it’s impressive that it only took him 14 years to redo his field guide, considering that it took more than thirty years for Peterson to redo his field guide, which covered far fewer species.

Anyway, I’m thinking about field guides because National Geographic sent me a sneak peek preview of the Seventh Edition of their field guide, which will be coming out this fall. And just looking at the opening title page, I was blown away.

The first four editions all had a great drawing of a perched Yellow-breasted Chat on that page, which was lovely. The Fifth Edition changed that to a flying Sandhill Crane, King Eider, and Baltimore Oriole, which made for a visually striking if ornithologically baffling combination. The Sixth Edition went to a flying Bald Eagle, beautiful and striking, even if they also used a Bald Eagle on the cover.

They used the same open-winged Bald Eagle illustration on every one of the first six covers. The Seventh Edition also shows a Bald Eagle, but this one is a new illustration of a perched bird by David Quinn.

The Seventh Edition title page spread shows six gorgeous hummingbirds, and the layout is visually appealing even beyond the charming beauty of the birds. The new edition has added more species: they’re now up to 1,023. The hummingbird plates are wonderful—they've been entirely revised except for Sophie Webb's Lucifer Hummingbird. They've added two pages of additional drawings and included more plumages as well as rare species. All the new hummingbird drawings were by Jonathan Alderfer and John Schmitt.

Jon Dunn and Jonathan Alderfer carefully selected which art pieces needed to be replaced or added, where a hint of habitat would be useful and which features to emphasize. They approved every sketch and painting. The artists used their own observations, archives of photographs, and museum specimens for reference.

I noticed little changes here and there that most people probably won’t notice, but that improved a great book to an even better one. For example, they changed the small flight drawing in the Sandhill Crane entry to a much more useful one. The original had the bird’s wings down, but now they’re held upward to make an easier comparison with the Common and Whooping Cranes on the same page.

The hugest change in the Seventh Edition came about thanks to ornithologists using DNA to revise entirely their taxonomic ordering of birds. So the birds are arranged differently in this guide, with pigeons, cuckoos, nightjars, swifts, and hummingbirds far closer to the start of the guide, well separated from the songbirds. Now hawks and owls are very close to each other, both well separated from the falcons. When I get the hard copy, I plan on re-reading this new edition cover to cover, to refresh my memory of seldom- and never-seen species, learn some new hints for identification, and absorb the new taxonomic order.

Jon L. Dunn has served as the principal author of all seven editions—as one of the top birders in the nation, he was an excellent choice, and the fact that he’s been at the top of his game since the 70s has kept the book both consistent and authoritative all along.

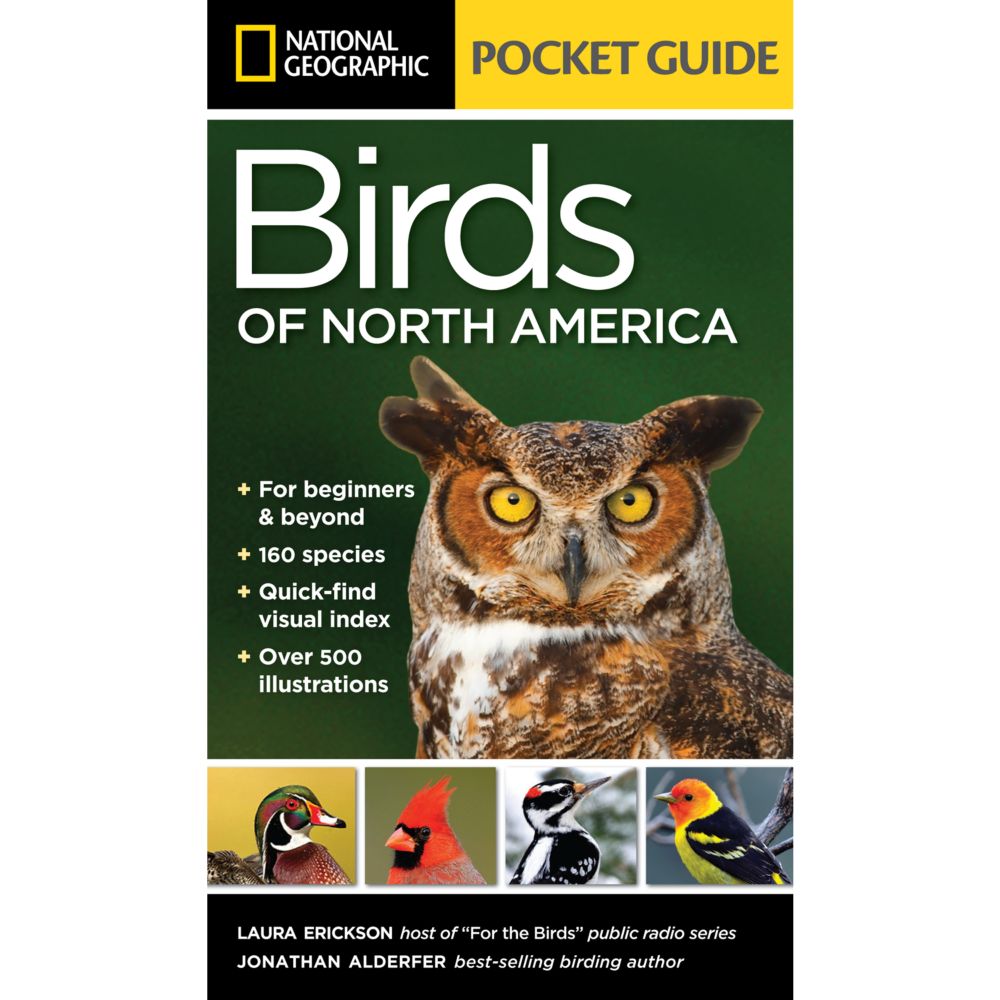

Jonathan Alderfer has been a principal author and artist of all recent National Geographic birding books, and has been the art consultant and principal general consultant of the field guide since the Third Edition. His name has been on the cover with Dunn’s as co-authors since the Fifth Edition. Jonathan is also the co-author of my own National Geographic Pocket Guide: Birds of North America—he was an exceptional working partner, having both a generous spirit and exacting standards.

The fantastic birder Paul Lehman has been the map consultant since the third edition. Like the rest of the book, the maps have both improved steadily and shown real changes in each species’ distribution from edition to edition, and no one knows more about species distribution in North America than Paul Lehman. The credit, "with maps by Paul Lehman" was added to the title page with the Sixth Edition.

In nature, evolution doesn’t make any organism “better”—it simply explains why those members of a population that best fit current conditions are the main ones to survive and reproduce. The evolution of the National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America is different—it's been a directed evolution. The National Geographic team started out making the field guide the “most current, authoritative, and comprehensive field guide available today—the ultimate, essential resource for the accurate identification of nearly a thousand species,” as the Fifth Edition’s cover states. Those words describe every one of the first six editions, and certainly are true for the seventh as well. If it started out as the gold standard for field guides, it's now gone platinum. No other publisher has been able to match National Geographic’s commitment to so frequently updating their field guide to keep it so very up to date. I can’t wait to get my hands on the real thing in September. Publication date is set for September 12; you can pre-order on Amazon.