|

My dog Pip atop my two volumes of The Birds of Minnesota. The books

weigh 12.4 pounds, almost 4 pounds more than Pip. |

In 1932, the University of Minnesota Press published

The Birds of Minnesota by Thomas Sadler Roberts. Roberts was far and away the most prominent ornithologist in the state—when the American Ornithologists’ Union was organized half a century before, in 1883, Roberts became one of the few original elected members. When the First Edition of

The Birds of Minnesota was published, the AOU’s journal,

The Auk, published a

long, very positive review of the two-volume, 1500 page tome.

Roberts's was the first work in Minnesota, and one of the first in the world, to include detailed information about precisely where and when each species of bird could be found, including breeding information, within the book’s coverage range.

The Birds of Minnesota sold out almost immediately, and just four years later, at the height of the Depression, it was reissued in an updated Second Edition.

Roberts, of course, hadn’t personally documented all the breeding activity in every corner of the state: birders here and there had been submitting information to him personally for years, and more formally via the Minnesota Ornithologists’ Union since it was founded in 1929. Birdwatchers throughout the country had been submitting data cards about bird sightings to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service since the 1800s as well. It was the collaboration of so many people, along with Roberts’s wonderful and charming descriptions of each species, that gave his work such longstanding value. Indeed, I quoted him here and there in my own

American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Minnesota published last year.

Year after year, we get new information as birds’ habits change. Every season countless birders reported their sightings to the MOU. In 1975, the University of Minnesota Press published Janet Green and Robert Janssen’s book,

Minnesota Birds: Where, When, and How Many, which updated the state’s seasonal and geographical information. And in 1987, the University of Minnesota Press published Robert Janssen’s updated version,

Birds in Minnesota.

Birdlife continues to change. In 2009, Audubon Minnesota and the University of Minnesota Duluth’s Natural Resources Research Institute, with funding from the Minnesota Environmental and Natural Resources Trust Fund (from proceeds from the Minnesota Lottery), coordinated efforts with professionals and volunteers combing the state to compile the state’s very first Breeding Bird Atlas.

This is not to be confused with the Breeding Bird Surveys that the US Geological Survey has been conducting since 1966—those involve 90 routes scattered throughout the state that are each surveyed just once a year, mostly in June. Participants count every bird seen or heard in a 3-minute time period at 50 stops. The Breeding Bird Survey gives us a great index to see, over time, which durnal species breeding in June are increasing, declining, or holding steady.

The state’s Breeding Bird Atlasers, 700 strong, scoured 2,353 townships, many of them multiple times over the entire breeding season, from mid-winter for owls, finches, and other early nesters through August for goldfinches and other late nesters, looking for solid confirmation of breeding. Some of the people conducting the Atlas surveys were trained students and professionals—my son Tom conducted some of the surveys—and others were volunteers—a few of my own sightings were entered into the database. During the process, the atlas project recorded more than 1 million observations, confirming 249 species breeding in the state. This project was not focused on population trends, but simply verifying where each species is now breeding.

I can't get over how splendid the Atlas is. It's

published online in an extraordinary and easily-accessible website. Each species account has a gorgeous and detailed map, which would have been valuable in and of itself, but the value is greatly magnified by the wealth of other authoritative information assembled by Lee Pfannmuller, Jerry Niemi, and the other authors, who used a great many resources to explain what we know about each species's range and its numbers from pre-settlement times through now, along with basic natural history facts. Each species account is both up to date and rich with historical information, all in one easy-to-find spot. Where available, the species accounts also include trend graphs from the Breeding Bird Survey and other valuable information. And the accounts are as beautifully written as they are detailed.

How have species changed over the years? About our national emblem, the

Bald Eagle, Roberts wrote: "Rare in winter. Formerly common, now much reduced in numbers and absent as a breeding bird from parts of the state where it once bred regularly.”

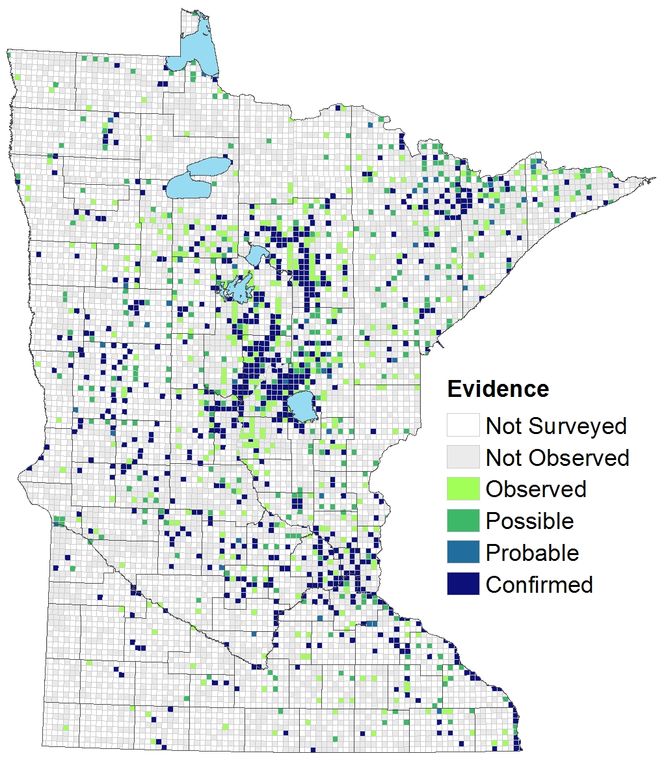

In 1975, Green and Janssen, in

Minnesota Birds: Where, When, and How Many, noted that the eagle bred primarily in the northern regions of the state, with the area producing the most young in the Chippewa National Forest, and that since the 1960s, the only known active nest sited in the southern half of the state was in the Upper Mississippi National Wildlife Refuge in Houston County.

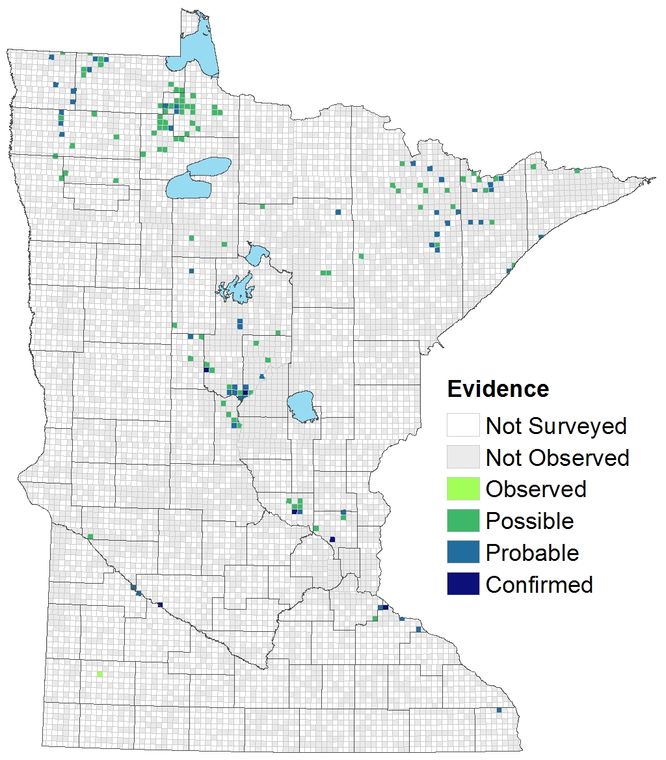

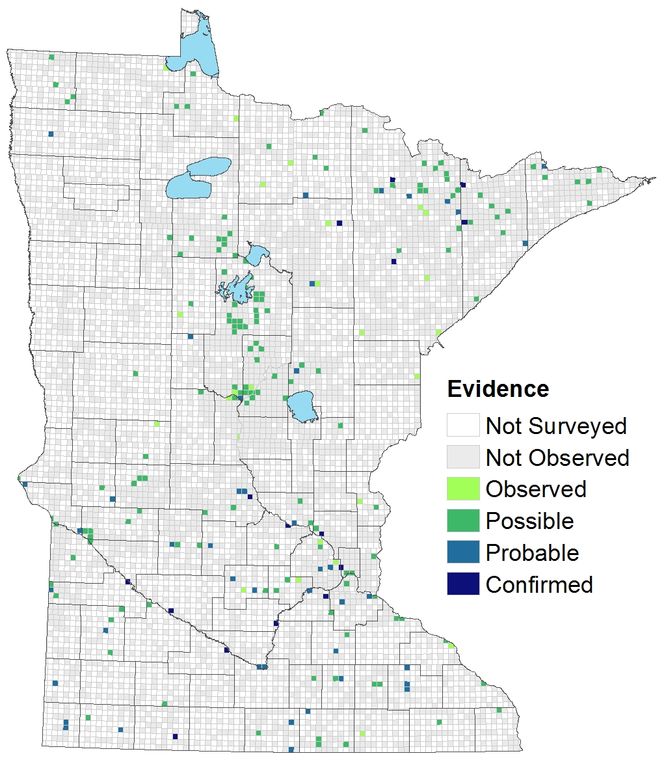

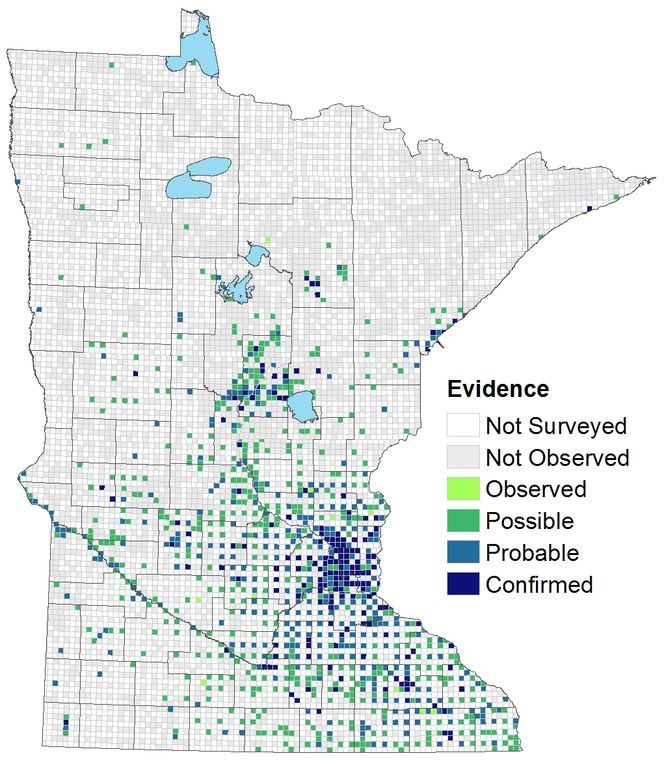

|

| From Green and Janssen, 1975 |

In 1987, after more than a decade of protection under the Endangered Species Act and more than a decade after DDT use was banned in the United States, Janssen wrote in his

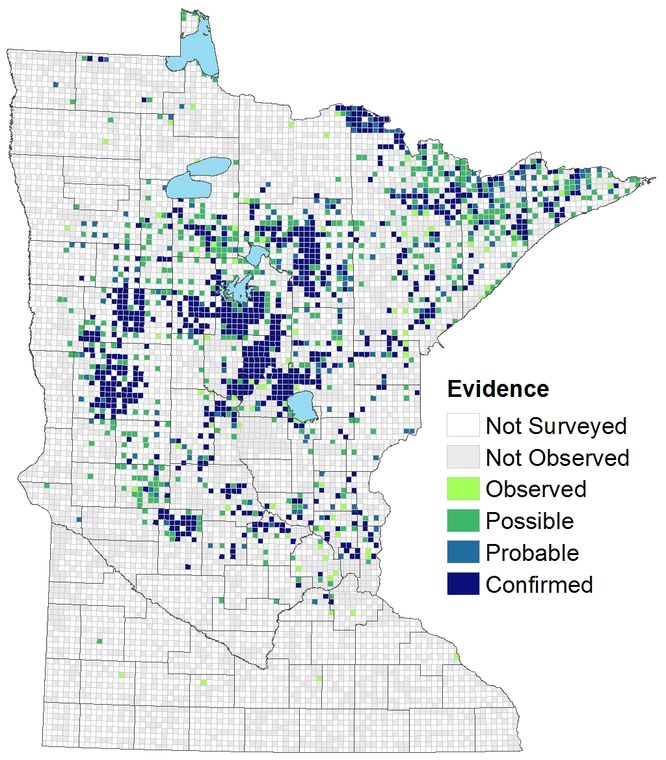

Birds in Minnesota, that a total of about 200 nests were known from the northern breeding areas and nesting territories were continuing to increase. At that point there were active nests both in Houston and Sherburne County.

|

| From Janssen, 1987 |

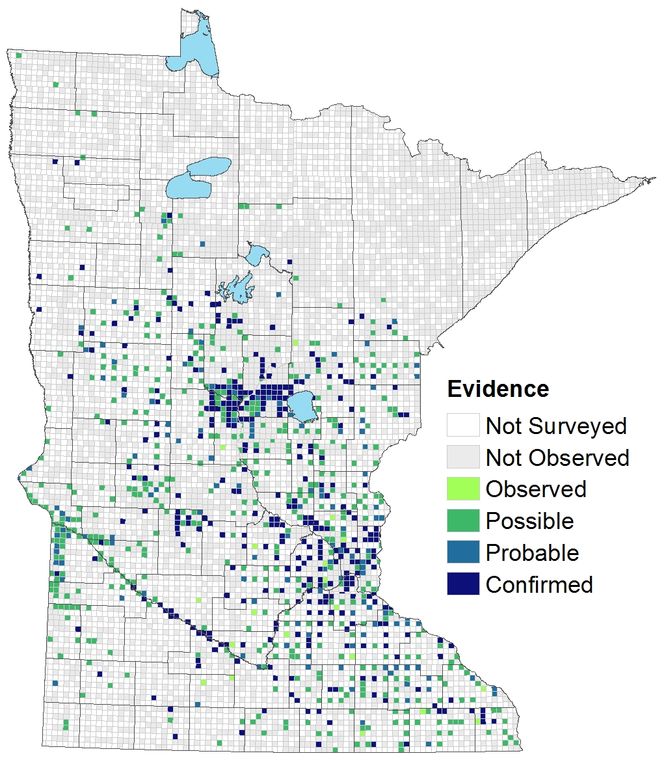

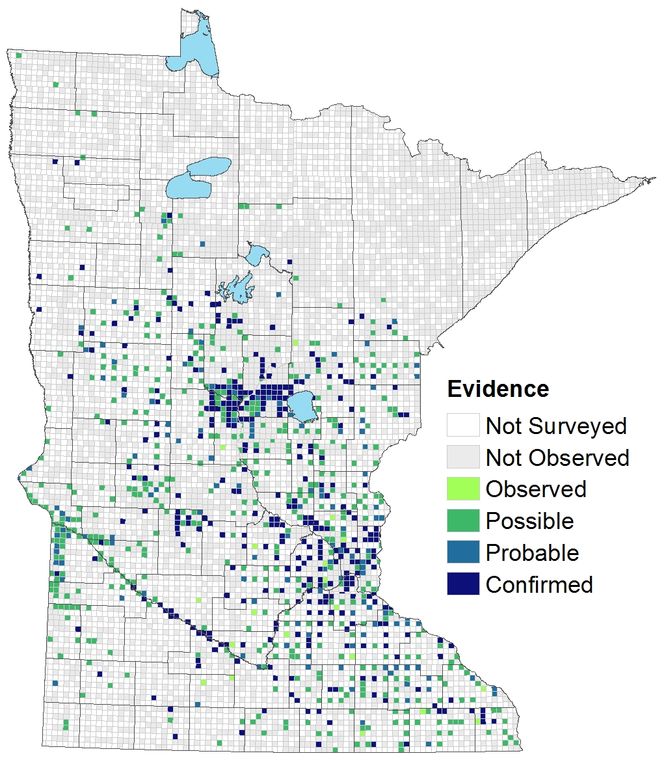

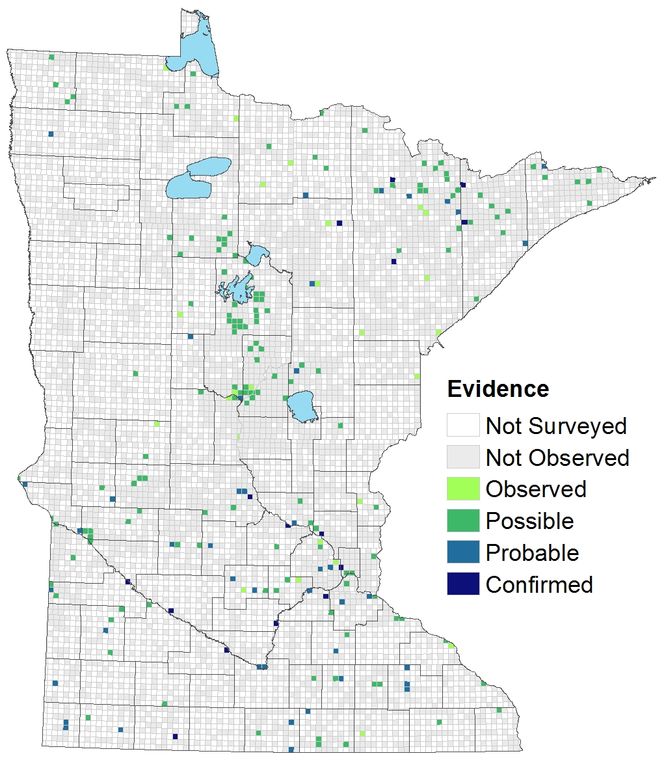

The Breeding Bird Survey shows steady low numbers from 1966 until the late 90s, when numbers started rising.

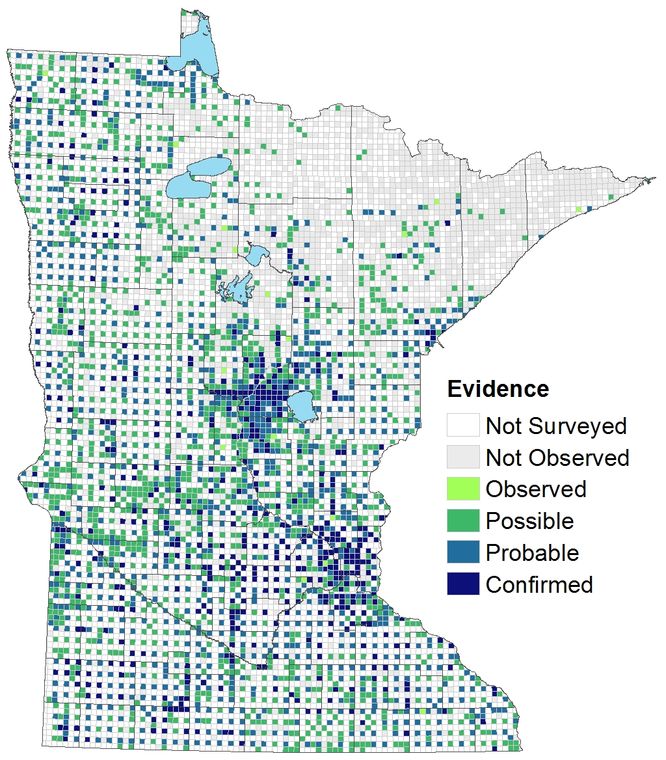

Minnesota’s Breeding Bird Atlas shows just how much more widespread nesting

Bald Eagles are today.

Having access to the three volumes of work makes it relatively easy for me to compare past and present. But the best thing about The First Minnesota Breeding Bird Atlas (2009-2013) is that I didn't actually need to go back to the earlier references: each individual species account includes all the comparison information!

How has our state bird, the

Common Loon, fared? The species account in

The First Minnesota Breeding Bird Atlas (2009-2013) begins with a continental picture in the Overview:

Although Minnesota supports the largest U.S. breeding population south of Alaska, the centers of greatest abundance are found in Canada.

Settlement of Minnesota led to a serious decline in loons here. The Atlas states, "Long considered the most iconic symbol of Minnesota’s northern wilderness, the Common Loon was actually a common resident of lakes throughout the state in the late 1800s and early 1900s." The Atlas also quotes two different sources affirming that the reason for the decline over the southern third of the state was indiscriminate shooting, and says, "today’s threats to the Common Loon are complex and wide-ranging," listing some of the ongoing threats from botulism and other disease outbreaks, especially in wintering areas; climate change impacts on coastal fish resources essential for wintering loons; mercury; lead fishing sinkers; and oil spills. On a hopeful note, it closes the Population Abundance section with this:

Historically, the Common Loon in the United States’ portion of the Great Lakes has experienced the greatest declines in both abundance and distribution (Evers et al. 2010). Indeed, the species has been extirpated in several states where it formerly occurred (Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, and Ohio), and its breeding ranges have receded northward since the late 1800s and early 1900s in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. Nevertheless, the Great Lakes region now supports over 50% of the U.S. breeding population of the Common Loon. As noted earlier, Michigan, Ontario, and Minnesota have recently documented small southern range expansions. Focused conservation efforts by resource agencies and local lake associations are surely one of the principal factors responsible for the population increases that have been observed across much of the species’ range.

Regarding historic information about

Wild Turkeys, T.S. Roberts wrote, “no eye-witness has left a written record so far as can be found and no Minnesota specimen is in existence.” I personally suspect that the introduction of Wild Turkeys here, which is inaccurately called a "re-introduction," will one day be considered as huge a problem for people and other species as the unnaturally high numbers of White-tailed Deer and

Canada Geese.

Like the turkey, there is little evidence that

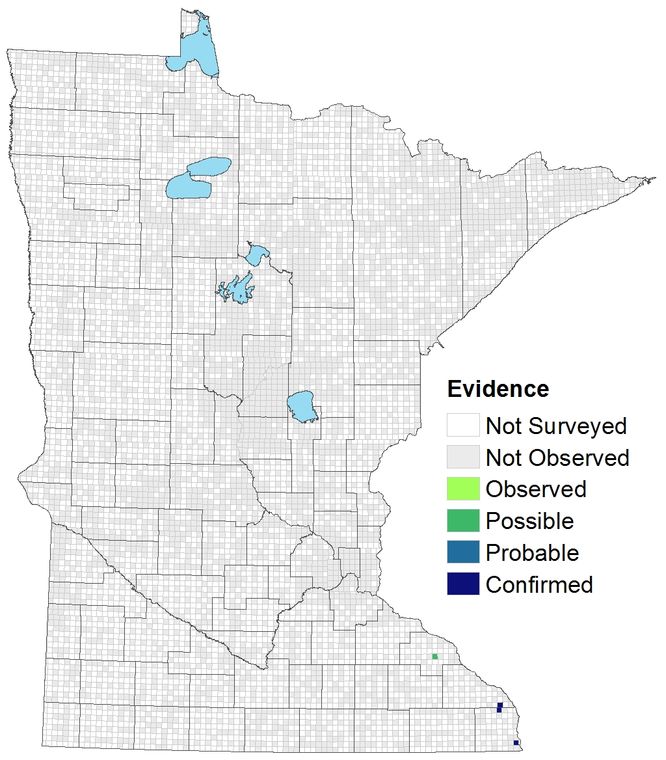

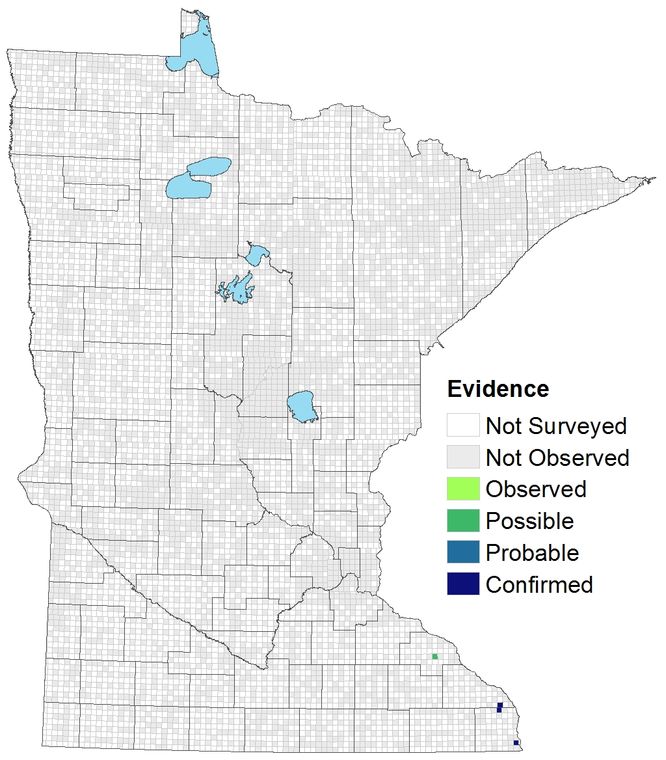

Northern Bobwhites were regular residents in the state before the pioneers settled. Some bobwhite may have expanded into the state from Wisconsin following the Hinckley fire, and some may have occasionally come up from native populations in Iowa, but for the most part, we can account for them by DNR and hunter group introductions. The Atlas says:

Regardless of how Northern Bobwhites came to occupy Minnesota in these early years, the population was sufficient to establish a hunting season from the 1920s through the early 1950s, when hundreds of birds were estimated to have been killed each year (Chesness 1964). According to a recent report by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, the bobwhite had been hunted since 1858, and the first recorded harvest was in 1919, estimated at 6,100 birds. The report concluded that during the 1920s, the estimated harvest peaked in 1927 (13,000 birds) and by 1932 it was confined to the southeastern area (Minnesota Department of Natural Resources 2015). Most of the nesting records given by Roberts were also from the 1920s. During this time period, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Division of Game and Fish was also releasing quail, but where, when, and how many are not known. These releases were terminated in 1952. As the numbers of harvested birds declined, hunting was also stopped in 1958...

The participants in the MNBBA recorded only 4 records, and all were close to the Mississippi River in the dissected uplands that drain directly into the river in Houston, Wabasha, and Winona Counties (Figure 2). There is no question about the identification of the species or that 3 of them are confirmed records. One record was just possible breeding evidence, and the observer guessed it was a released bird. Without better official monitoring and research about the origin of these quail, as well as others in the southeast, there is no way of knowing if they are native or released.

I hear reports of Bobwhites turning up in my own neighborhood in Duluth periodically. These birds are escapees from a retriever training club. They can't survive long up here, especially in winter.

Hunters often tell me that to bring back any endangered bird, just make it a game species. Unfortunately, the Sharp-tailed Grouse and Greater Prairie-Chicken, two of our state's most splendid game species, aren't doing so well even as the

Minnesota DNR encourages hunters to try for the "Minnesota Grand Slam," when a hunter shoots one each of our four native grouse species—Ruffed Grouse, Spruce Grouse, Greater Prairie-Chicken, and Sharp-tailed Grouse—within the state in a single season.

The

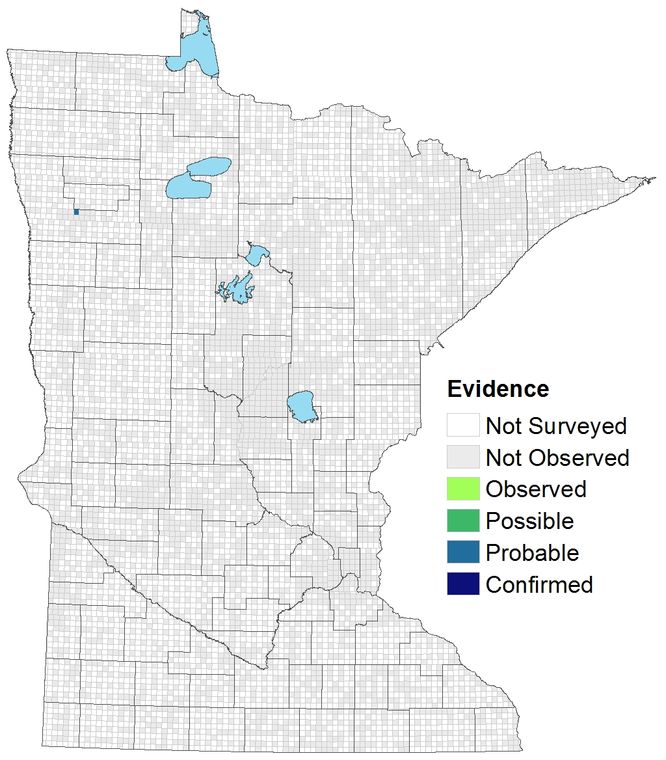

Greater Prairie-Chicken is a "relative newcomer to the state’s western grasslands, having forced the northern retreat of the truly native grassland grouse, the Prairie Sharp-tailed Grouse." Even so, the prairie-chicken's range has shrunk in recent decades.

According to Roberts, the

Sharp-tailed Grouse, our state's only indigenous prairie grouse, was originally found in “the prairies in the summer and … the brush-lands and open forests in the winter, and the early explorers and first settlers found it abundant everywhere.” According to the Atlas site,

Due to ... habitat issues, the species is officially listed as a Species in Greatest Conservation Need. The National Audubon Society labeled the Sharp-tailed Grouse as “climate endangered” and predicted a 76% loss of the species’ summer range by 2080 with changes in climate. The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources has a Sharp-tailed Grouse management plan that has been hampered by funding and implementation issues.

One very sad decline in the years since I started birding has been of the

Red-headed Woodpecker. This gorgeous bird was always rare in northeastern Minnesota, and overall, its range hasn't changed much: the Atlas notes, "Overall, the breeding distribution of the Red-headed Woodpecker has changed very little since Roberts wrote the first comprehensive account in 1932." But Breeding Bird Survey numbers since 1967 have shown a dramatic decline. In Minnesota the Red-headed Woodpecker has been designated a Species of Greatest Conservation Need by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Audubon Minnesota designated it a Target Conservation Species and prepared a statewide conservation plan. The plan adopted the national population objective for the species and outlined actions necessary to accomplish this goal, including protecting and restoring oak savanna habitat.

|

MY Red-bellied Woodpeckers. This pair is feeding young in the first documented

nest in St. Louis County. |

Another woodpecker, the

Red-bellied Woodpecker, is doing amazingly well, not only expanding its range north but also becoming more abundant throughout its range in the state. In 1892, the species was unknown in the state; Roberts noted the first one he ever saw in the state in 1898. It continued to expand from the southeastern corner north and west through now. We've had solid evidence of red-bellieds breeding in St. Louis County for several years, with birders noting newly fledged young here and there in Duluth. In 2016, the first actual nest in the county was found in my own backyard; this nest in a box elder fledged at least one young.

The

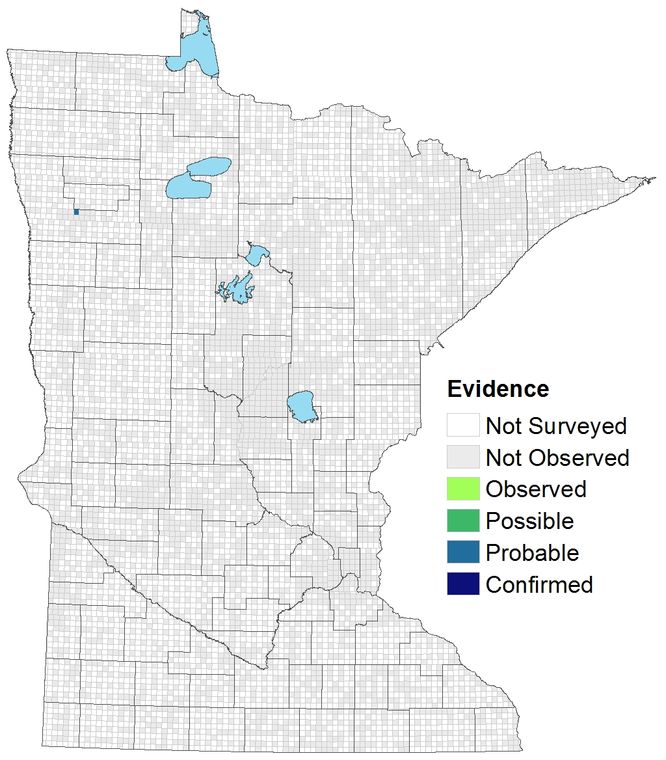

Burrowing Owl's status in Minnesota is extremely difficult to tease out. The Atlas provides a nuanced picture of what we know. We've had two successful nests in the state in this century, the last in 2007.

Over the years, I can't begin to recount the number of times people have asked me about a bird they remember from childhood that they just don't hear anymore, the Eastern Whip-poor-will. Because of its nocturnal habits, we don't have Breeding Bird Survey information about it, but those same nocturnal habits made it very conspicuous to explorers and pioneers who wrote about it as well as Minnesota's early ornithologists. It was considered common or abundant from sites as widespread as the Red River valley, central Minnesota, and the Twin Cities. I think this is a classic case of an obligate insectivore declining in response to declining numbers of moths and other flying insects. Scientists, especially in the U.K. and Europe, are finally starting to find ways of quantifying declines of insects from decades past. As we figure out how to do that here in Minnesota, I am confident that we'll start understanding more about the declines of the Whip-poor-will, Common Nighthawk, and Purple Martin.

Many of us remember when

Common Nighthawks nested on flat roofs in towns and cities. I loved hearing them peenting in the evening sky in downtown areas from New Orleans to Chicago and New York City. But nighthawks, who are defenseless against predators when they can't take off, didn't survive the urbanization of gulls and crows, both which are omnivorous predators. There still are lots of nighthawks, but nowhere near as many as in recent decades. Partners in Flight has designated the nighthawk a Common Bird in Steep Decline. It's also designated as a Species in Greatest Conservation Need by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources.

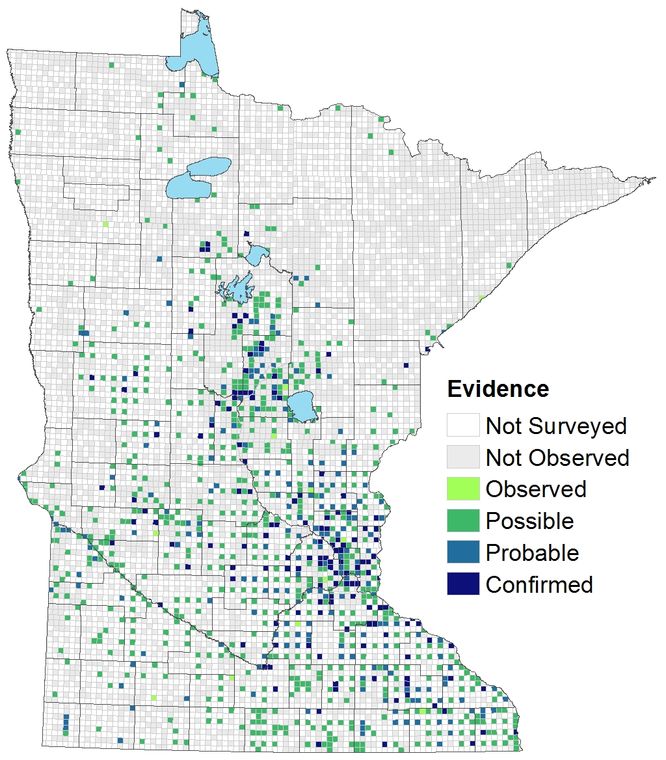

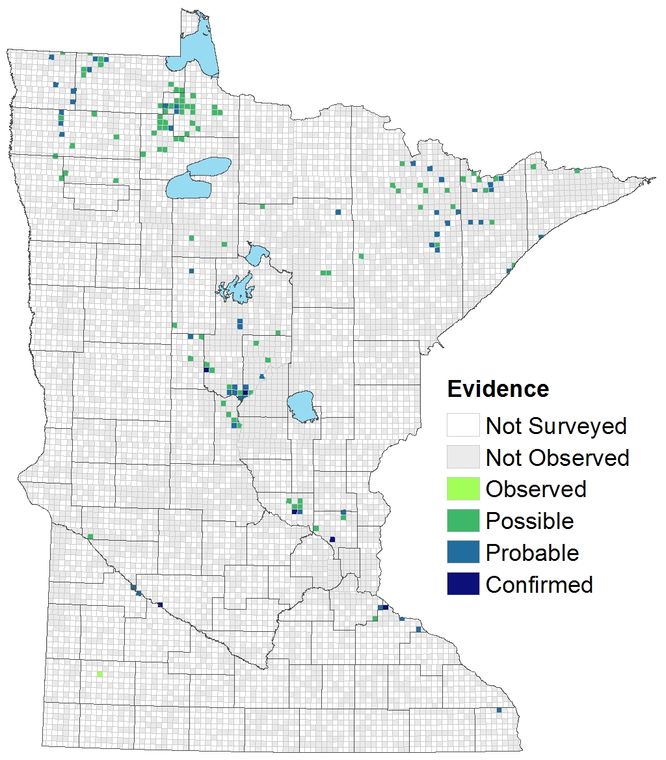

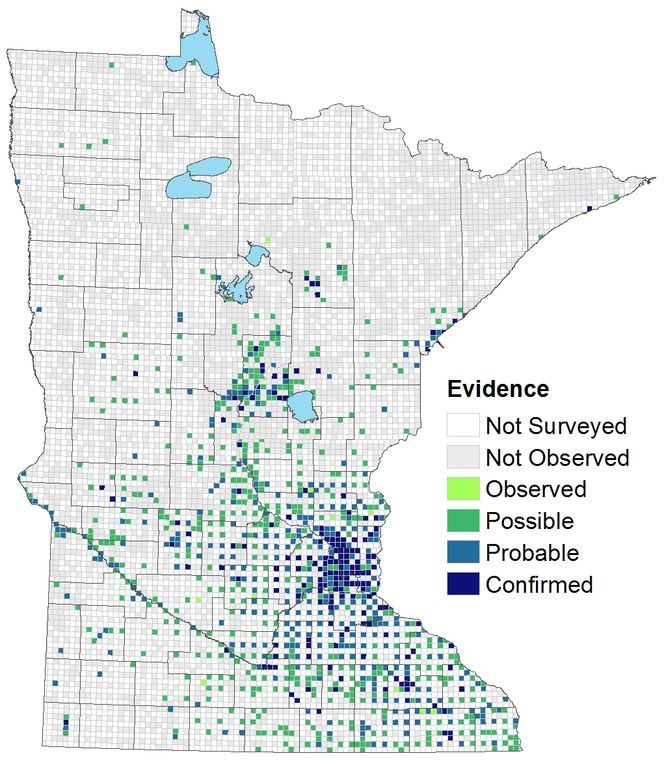

On a happier note, the

Northern Cardinal is doing quite well. Originally, the species' range ended south of Minnesota—our first record was in Minneapolis in the fall of 1875, but little by little it became established as a permanent resident throughout the Mississippi Valley south of Red Wing, and from there it has continued to spread. Roberts reported nesting as far north as Hennepin County and as far west as Owatonna. Now it's a regular nesting bird in Duluth and other isolated places in the northern third of the state, and has become fairly abundant in the southern two thirds, except its more scattered in far western Minnesota.

One of my favorite birds of all, the

Evening Grosbeak, used to be much more abundant in northern Minnesota. I was thrilled with this particular Atlas species account because it provided a fair and balanced examination of both the widely held belief that their high numbers from the 1960s through the 80s were an aberration, Evening Grosbeaks previously being fairly uncommon in the Great Lakes area; and my own argument that they were fairly common in our area long before the 60s such that the decline since the 1980s is very troubling. The species account includes lots of supporting evidence for both arguments, allowing readers to come to their own conclusions. Whatever the early history of the species, all of us who remember their former abundance can't help but feel sad for their decline.

I'll be thrilled if the University of Minnesota Press issues the Breeding Bird Atlas in book form—I'd be one of the first to buy it, and would keep it next to my well-worn copies of The Birds of Minnesota, Minnesota Birds: Where, When, and How Many, and Birds in Minnesota. But even if it never gets published as a book, the online version is so complete and easy to use, with so much valuable information, that I'll be consulting it frequently from now on.

Pfannmuller, L., G. Niemi, J. Green, B. Sample, N. Walton, E. Zlonis, T. Brown, A. Bracey, G. Host, J. Reed, K. Rewinkel, and N. Will. 2017. The First Minnesota Breeding Bird Atlas (2009-2013).