In 1974, when I received my first field guide for Christmas, it was like opening the Sears Christmas Catalog—what we children called the “wish book.” A whole big section showed what seemed like every toy in the world.

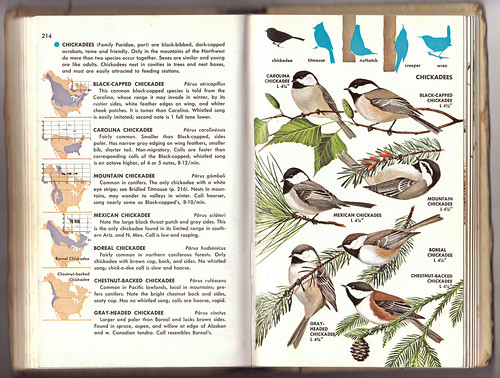

My first field guide was like that—showing so many thrilling possibilities, out there waiting for me. Some of the birds pictured I’d have to travel to see in real life—ptarmigans like the ones White Fang encountered in one of my favorite children’s books, California Condors and Everglade Kites that were appearing on posters supporting the Endangered Species Act, and puffins and Roseate Spoonbills, which looked too impossibly bizarre to be real. But according to the range maps, some of the coolest looking birds could be found right near me— Common Loons, Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, Blackburnian Warblers, Pileated Woodpeckers! So many treasures, beautiful on the page, and now I could imagine seeing them in real life!

That field guide gave me the tools to identify birds, but much more important, it issued both an invitation and a personal mandate to go out and look for them. That little book was my very own Passport to Adventure.

During my first year of birding, I did manage to find in the field guide most of the birds I saw. I quickly learned that the challenge of identifying each bird could be both enjoyable and rewarding, but more importantly, I learned that the identifications were hardly ever the most enjoyable or rewarding elements of a day with birds. Indeed, sometimes it felt more rewarding to just stop and look at them, without teasing out each identification. One of the most pleasurable days of my first year of birding was spent in a railroad yard watching pigeons—seeing their muscular wings in action, drinking in their noisy takeoffs and powerful wing beats in direct flight, and thrilling at how they hold those wings in a steep V as they rock slightly back and forth in soaring flight. It was a wondrously satisfying three or four hours that I still remember with a smile.

Knowing the names of things is a primal urge for our species, referenced as long ago as Genesis, with Adam naming all the beasts and all the fowls of the air. Children quickly need a more precise word than dinosaur for Triceratops, Stegosaurus, Brontosaurus, and Tyrannosaurus.

|

| Not just ANY dinosaur--these are Stegosauruses! |

If I tell you a story about a bird and want you to be able to picture it the way it looks to me, calling it a brilliant red bird with black wings might not give you a picture of the Scarlet Tanager, Hawaiian Iiwi, or Vermilion Flycatcher I was trying to describe. The precise vividness of a name can be valuable.

You can, of course, take the precision of bird identification too far. About birds, Walt Whitman wrote:

Many I cannot name; but I do not very particularly seek information. (You must not know too much, or be too precise or scientific about birds and trees and flowers and water-craft; a certain free margin, and even vagueness—perhaps ignorance, credulity—helps your enjoyment of these things…)Even if you don’t want to go beyond Whitman’s free margin, a good field guide can inspire you to go a-looking for those birds and trees and flowers. Which one should you get?

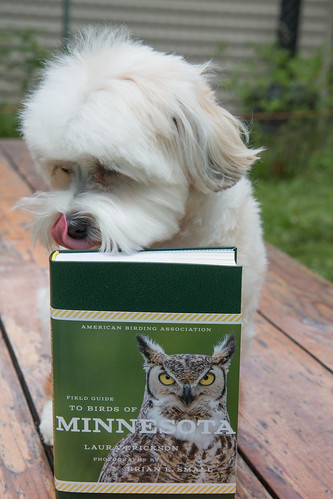

My three favorite bird field guides are the National Geographic if you want the most comprehensive guide, the Kaufman Field Guide to Birds of North America if you want a comprehensive North American guide that uses photos and is the one kids usually like best, and the ABA state field guides if you want a pretty comprehensive guide to just one state. I happen to have written the Minnesota one.

But just as Walt Whitman bundled birds with trees and flowers, when we go out looking for birds we see a lot of other elements of nature. One field guide is perfect for even the most advanced birder who notices other things out there as well.

The one book I recommend for every man, woman, and child in the Midwest is a field guide, but not just a field guide to birds. Even those of us who are almost exclusively focused on birds can’t help but notice some non-avian animals and plants outside, or looking up at the night sky while out owling. The Kaufman Field Guide to Nature of the Midwest makes puzzling out these features of nature simple and straightforward, enriching our outdoor experiences. If I were to recommend a single book for a nature-lover, this would be it. The Field Guide to Nature of the Midwest includes not just a great many animals and plants—it even shows the constellations in the sky.

Since it’s a pocket-sized book, it clearly cannot show all the living things of our area. Well over 400 species of birds have been seen in the Midwest, of which this guide covers about 265 of the most common bird species. That leaves out quite a few, but the species are well chosen. I’d been an avid birder, going out daily for almost four months before I encountered the first species, Swamp Sparrow, that isn’t included in the Field Guide to Nature of the Midwest. For comparison, by that point in my birding, I’d seen 17 species that aren’t included in Stan Tekiela’s little Birds of Minnesota field guide. If you come up here to northern Minnesota for our famous owl invasions, you’ll have to recognize the Boreal and Northern Hawk Owls on your own, but it does include Gray Jay, Black-billed Magpie, Boreal Chickadee, both crossbills, and several of our other winter finches, as well as the rest of our owls.

And beyond birds, the Kaufman Field Guide to Nature of the Midwest includes fine samplings of the wildflowers, trees, other plants and fungi, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, fish, butterflies and moths, other insects, and spiders. And each section has an inviting explanation of how to enjoy that element of nature.

If you get fascinated by a single group, as I am with birds, you’ll certainly want to add a more comprehensive field guide. For birds, the simplest choice when available for your state is one of the new ABA state field guides. In the Midwest, we have the one I wrote for Minnesota, Michael Retter’s ABA Field Guide to Birds of Illinois and Allen Chartier’s one for Michigan, which will be out very soon—it’s at the printers. Outside the Midwest, ABA now has these state field guides for Florida, Texas, Arizona, Colorado, New York, Massachusetts, the Carolinas, California, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey.

For an all-encompassing guide to the birds of the whole continent, if you want one with photos, I recommend the Kaufman Field Guide to Birds of North America, or if you prefer drawings, the National Geographic Field Guide to Birds of North America—their new 7th edition is now available, with the most up-to-date species names and taxonomic order of any guide.

But none of those bird guides will tell you what that pretty flower next to the path is, or the kind of tree that Great Horned Owl is roosting in, or what that big orange butterfly that has way too many spots for a Monarch could be.

When taking a family walk, you may prefer Whitman’s vagueness and free margin more than researching every single thing. But if you want to learn the name of a particular plant or animal to help you commit it more firmly and clearly to memory, the Kaufman Field Guide to Nature of the Midwest will provide plenty of assistance. And thumbing through it at home may fill you with the inspiration to get out there looking in the first place. It’s a true Passport to Adventure.