Yesterday, I received a letter from Rachel Fellman, an archivist at the Charles M. Schulz Museum in Santa Rosa, California. She writes:

Dear Laura: …We’re tidying up a collection of his fan mail from the late ‘90s, and in the process came across your witty and informative letter … speculating on Woodstock’s species. It’s particularly apropos because we are planning a[n] exhibit about Woodstock for next year.

At this point in his career, Schulz was overwhelmed with mail and rarely answered letters – however, I wanted to ask if he did reply to you? You ask such interesting questions, and as a lover of obscure facts, I’m sure he enjoyed your ideas about Woodstock’s plumage and his distinctive flight pattern.

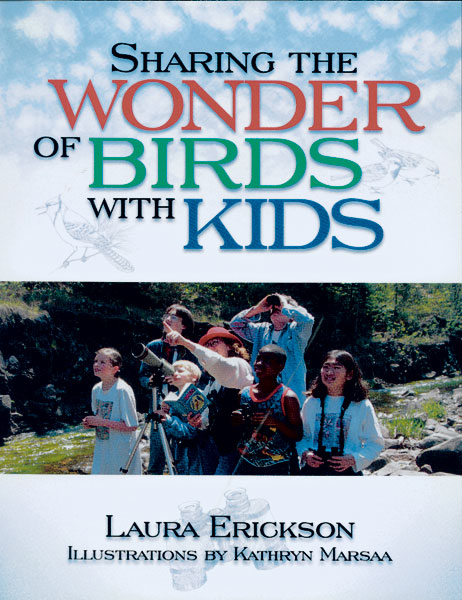

Ms. Fellman included a copy of my letter, which I’d written on February 2, 1996, when I was writing my book, Sharing the Wonder of Birds with Kids.

I’d written:

Dear Mr. Schulz:

I am writing a book for parents, grandparents, Scout leaders, naturalists, and teachers, about how to teach children about birds. My publisher … plans a September release. I emphasize the vast array of birds in the world around us, some outdoors and some closer to home, like on the comic page. Since one of my favorite birds is Woodstock, I would love to include information about him. I would deeply appreciate it if you would answer one or two of the following questions that I could quote in the book.

What inspired you to create Woodstock? Might it have been, in part, to provide Snoopy with an outdoorsy friend to highlight Snoopy’s more urbane interests? To show how Snoopy, as America’s most genuine individualist, doesn’t interact with birds in ways that other beagles do?...

Did Snoopy ever figure out what kind of bird Woodstock is? Last I recall, he was “thumbing” through a field guide and speculating that he might be a Ruby-crowned Kinglet, though I can’t find that strip and don’t have a clue where it might be indexed. As an ornithologist and avid birder, I’ve noted that Woodstock’s flight pattern is exactly like that of a Cedar Waxwing after eating fermented berries, his plumage rather like a Yellow Warbler’s, and his crest like a Great Curassow or a Resplendant Quetzal. I might have guessed that he was a unique hybrid of these species except that his friends look just like him. So my conclusion is that they belong to a rare and unique species thus far undescribed in the ornithological literature.

Ornithologists classify birds primarily by analyzing mitochondrial DNA and other cellular samples from blood and other tissue, and a thorough examination of the skeleton, but I assume Woodstock doesn’t want to donate tissue samples and his skeleton is obviously still in use. There have been rare cases where a newly discovered species was named based on drawings or photographs. Since you are the only person who has actually seen Woodstock and drawn him from life, you are the only one qualified to assign him common and scientific names. Have you considered doing this?

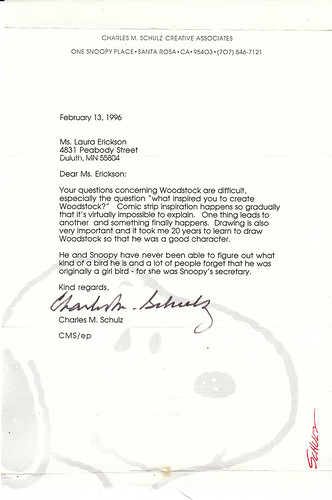

Woodstock (and his unique relationship with Snoopy) appeals to the child in everyone. I would deeply enjoy the opportunity to provide information of substance about him. Thank you for your help.Charles Schulz indeed responded to my letter. Less than two weeks later, I received this charming letter from him:

Dear Ms. Erickson:

Your questions concerning Woodstock are difficult, especially the question “what inspired you to create Woodstock?” Comic strip inspiration happens so gradually that it’s virtually impossible to explain. One thing leads to another and something finally happens Drawing is also very important and it took me 20 years to learn to draw Woodstock so that he was a good character.

He and Snoopy have never been able to figure out what kind of a bird he is and a lot of people forget that he was originally a girl bird – for she was Snoopy’s secretary.

Kind regards,

Charles Schulz.

Next year’s planned exhibit about Woodstock at the Charles M. Schulz Museum sounds right up my alley. I hope I can get to Santa Rosa to see it!

** (added as a postscript) **

By the way, I did use this information in my book, Sharing the Wonder of Birds with Kids. On Page 3, in Chapter 1, "The Magic of Birds," I wrote about birds children see in everyday life.

If there's no way to determine the answer to a question, encourage kids to guess. How do you think the Nintendo company came up with the design for Mario's "Koopa-Troopas," which look like turtles but sometimes have bird wings? How might Charles Schulz have come up with the idea for Woodstock? I wondered about that, so I wrote him a letter. He responded, "Comic strip inspiration happens so gradually that it's virtually impossible to explain. One thing leads to another and something finally happens. It took me twenty years to learn to draw Woodstock so he was a good character." If not even the creator of a cartoon character understands how he got his ideas, kids obviously can use their imaginations to guess.In a sidebar on Page 58, in Chapter 4, "Bird Identification Starters," I wrote:

Is Woodstock a warbler? When I asked Charles Schulz what species Woodstock is, he wrote, "He and Snoopy have never been able to figure out what kind of a bird he is." Schulz reminded me that Woodstock "was originally a girl bird, for she was Snoopy's secretary."