In the late 1990s, I circulated a petition trying to get the Black-capped Chickadee named Minnesota’s Emergency Auxiliary Backup State Bird, to serve during the six months of every year when loons have flown the coop and are not fulfilling their obligations. I got a few thousand signatures, my DFL precinct caucus voted in favor of it, and if I recall correctly, my congressional district convention approved it too, but that’s as far as it went. It was a lot of work on a fun campaign. I failed, but at least we still have a state bird, absent half the year though it may be.

School mascots are like state birds—not all that important in the overall scheme of the universe, but at their best, they provide a unifying symbol of community spirit and shared identity. My adult children have forgotten a lot of details about their elementary school but still remember the Lakeside Lion because of the funky design and colors on school supplies and sweatshirts.

Elementary school mascots have less impact on us beyond childhood than high school and college mascots do—I can’t remember what my elementary school’s mascot was, but I do remember the West Leyden Knight. When I started college at the University of Illinois in 1969, the mascot was “Chief Illiniwek.,” which even in my ignorance at the time seemed offensive. In 2008, the university finally got rid of that shameful stereotype, and in 2011, a campus survey of 11,440 U. of I. students revealed that 85 percent supported the decision. But in the 14 years since, the university hasn’t replaced the mascot with anything else.

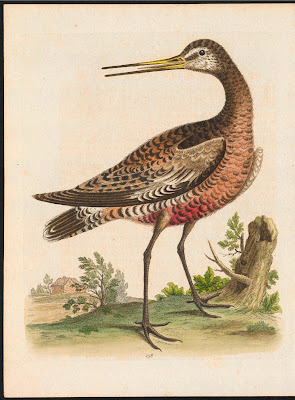

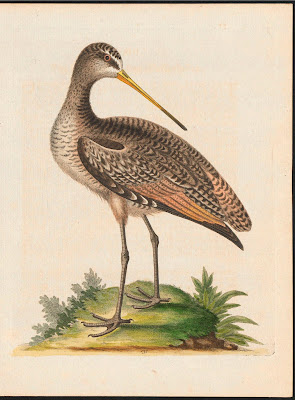

To fill that vacuum, in 2019, a fun, determined, and talented astrophysics student, Spencer Hulsey, spearheaded a campaign to name as mascot a splendid blue and orange bird.

The Belted Kingfisher has a lot going for it besides bearing the school colors. The powerful, heavy beak and shaggy crest give it the proportions of an athlete, especially one wearing a funky helmet; and kingfishers exemplify skill, concentration, and focus as well as power, making them an excellent choice for a school that excels in academics and sports both. And unlike many mascots and a certain state bird I could mention, the Belted Kingfisher lives right there in Champaign-Urbana year-round. Its loud rattle would make a perfect battle cry for any sporting event and is mechanical enough that some enterprising individual is bound to make a cool noise-making toy mimicking the sound that could create a craze like the vuvuzela did in the 2012 Olympics only, with luck, less damaging to our eardrums. Spencer and her friends suggested a giant Kingfisher Kazoo. What could be more fun?

|

| UIUC student Keegan Thoranin drew this kingfisher |

One little-known fact about the Belted Kingfisher makes it especially appropriate as a football team mascot—it’s one of the few birds that form huddles. Nestling kingfishers stay in a tight huddle, wings snugly wrapped around one another even as they shuffle about in their dark nesting burrows.

That huddling can also be construed as a group hug that could endear the birds to the most sports-averse students as well as football fans. And that is exactly what a mascot should do: appeal to the many diverse interests and passions of a university community.

Spencer Hulsey created a lot of engaging illustrations to promote the kingfisher and gave me permission to post them on my blog.

In 2020, she presented her case to the University of Illinois Senate who passed the resolution 105 to 4, but the endorsement legislation is still sitting on the Chancellor's desk. Now her group is focused on building community support so the chancellor can see they mean business. She said that ultimately, their work “proved to him that the campus and faculty are ready for a new mascot, and we expect he will vote to adopt a new mascot before Spring 2024. The kingfisher is the only contender at the moment, but the floor could be opened to other suggestions.” The Kingfisher website includes information about how we can join the Letter Campaign to most effectively support making this splendid and fun bird U. of I.’s official mascot.

%20-%20Copy.png)

.png)