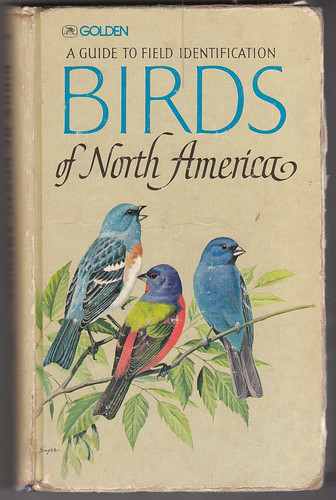

On Christmas 1974, my mother- and father-in-law gave me two wonderful gifts: my first pair of binoculars, and a copy of Peterson’s A Field Guide to the Birds. I devoured the book, reading every page while thumbing back and forth between the written species accounts and the illustrations, which were on separate plates. Then I discovered another bird field guide out there, even more beautiful and useful, the “Golden Guide.”

|

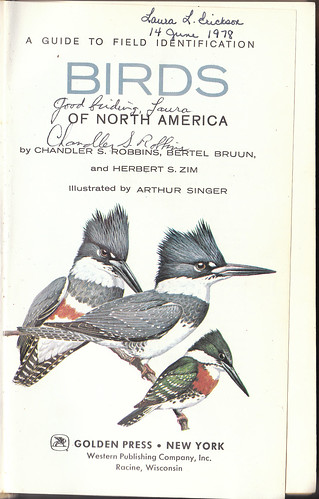

| This is actually my second copy of the Golden Guide: I found it in hardcover in a local bookstore right when the pages started falling out of my first. |

This second field guide was the book I fell in love with, the one I brought with me on every birding expedition that spring, when I saw my first chickadee and 39 other species, and for the rest of the year, as I saw 80 more new species. It's the field guide that carried me through two ornithology classes and helped me identify more than 400 of the first birds on my lifelist.

Yet unlike the Peterson guide, no author name was listed on the Golden Guide cover, much less embedded into the title. An author credit was given to three men on the title page, and it wasn’t for a couple of years that I learned that the primary author of the book—the one who wrote the text for each species and most of the other parts—was the first one listed, Chandler Robbins. This modest and unassuming man wasn’t the least bit interested in self-promotion or taking more credit than the people he worked with.

I met Robbins soon after learning his part in creating the Golden Guide. I was teaching at St. James Elementary School in Madison, Wisconsin, when the American Ornithologists’ Union met there in 1978. I volunteered to help the curator of the university zoology museum by setting out bird specimens and guiding the visiting ornithologists through the open house. I also wrote a poem for the AOU’s parody journal, The Auklet (“Happy Traill’s to You, or Ornithologists Take Their Lumps and Split”), and led a field trip to my favorite local birding spot—Picnic Point.

The meeting was held in mid-August, after birds have pretty much stopped singing for the season but before much migration has kicked in. So it felt dreadfully presumptuous for me, an elementary school teacher who’d only been birding for 3 years, to be leading professional ornithologists on a field trip at all, much less in August when there were so few birds to show them. Fortunately, two of my American Redstarts were still singing, allowing me to explain how to tell them apart by slight differences in their songs. I also happened to know where a mother Virginia Rail was still hanging out with two or three chicks. I was shocked that she was a lifer for some of them—I presumed that professional ornithologists would have seen far more species than I had.

We saw about as good a list as was possible at Picnic Point in mid-August, the redstarts and rails like icing on the cake. But this shy teacher was so intimidated by professional ornithologists that my hands holding binoculars were visibly shaking. Fortunately, one older, quiet-spoken man with a crew cut started asking me leading questions right off, and kept that up as we walked along, helping me focus my commentary throughout the field trip, making it a wonderful success.

As our group was breaking up, he told me how pleased he was to have come, mentioning that his brother had told him that if I was leading a field trip at Picnic Point, he should go. I was floored, never imagining that anyone would even think of me as a field trip leader, much less specifically recommend me. And then he then told me who his brother was: Sam Robbins, perhaps the premier birder in the entire state, who was working on his magnum opus, Wisconsin Birdlife. Sam was kind and gentlemanly just like this warm stranger, so I asked him what his name was, and he said “Chandler.”

Miraculously, I didn’t faint. And fortunately, expressions like “Holy crap!” weren’t in my lexicon at the time, since he was such a proper gentleman. But that left me dumbfounded—utterly tongue-tied meeting the man who had written my birding Bible. I can’t remember what exactly I stammered in response.

I had a free ticket to the banquet because I'd helped with so many events, but going to any social event with strangers was hard for me. When I walked into the huge banquet hall, the tables near the front were all filled, but I didn’t care—I was headed for a dark corner in back where I could sit by myself during the meal and program and then quietly disappear into the night. But I’d only taken a few steps in before Chandler Robbins walked straight up to me and asked if I already had a table—he’d saved a seat for me! On the short walk there, we were stopped by several ornithologists and graduate students, all telling him how much they loved his work and plying him with questions or asking him to review a paper or book for them.

I still wonder what it was about that shy 26-year-old teacher, improbably still wearing braces on her teeth, that made Chandler Robbins single me out as a dining companion when he had so very many better choices. It was one of the most thrilling evenings of my life—he was so fun to talk to, and so interested in my work teaching fourth, fifth, and sixth grade science and music. He asked questions about how I incorporated nature study into the classroom, and how I had started paying such close attention to the songs of individual birds. I of course found him far more interesting than me, and kept trying to work the conversation back to him—his field guide and especially the brilliant decision to include sonograms for each species in it, his field work, and anything else I could tease out of him. Looking back, that lovely dinner was wasted on a woman who was cosmically ignorant of this man’s many accomplishments, especially because he was too modest to call my attention to some of the most amazing things about him.

It was only later that I learned that during the 1950s, he led the effort to save the albatrosses on Midway Island. He did seminal research about forest fragmentation and other habitat issues that helped provide the underpinnings for the conservation work protecting the Chesapeake Bay. He wrote some of the seminal papers about pesticides that inspired and provided the essential information for Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring—indeed, he was the one who designed important DDT studies at Patuxent, with biologist Rachel Carson serving as his technical editor. And in 1966, to ensure that we’d have a consistent body of data to track breeding bird numbers over years and then decades, he started the incredibly important Breeding Bird Survey. Any one of these accomplishments would have made him a hero—I had no clue whatsoever that the man who invited me to sit at his side during the AOU banquet had done all of them. The closest we got to discussing any of this was when he asked if I had a Breeding Bird Survey route, and I confessed that I didn’t think I had enough experience to do one yet. He told me not to sell myself short, but I figured he was just being nice.

Five or six years later, after Russ and I had moved to Duluth, Russ found out that Chandler Robbins was giving a seminar at the NRRI that very afternoon. Russ took personal leave to come home and stay with the kids so I could attend. I walked into the seminar room with just a few minutes to spare. Instantly Chandler Robbins charged over and said, “Laura, I don’t know if you remember me, but my name is Chandler Robbins.”

Over the years, I ran into him only a few more times. He stayed the same quiet, unassuming gentleman. I spent the most time with him in Guatemala in 2007—the only time I’ve ever had the courage to ask if I could get a photo with him.

We had lunch together one day, and while he was getting his food, I took a picture of his binoculars on the table. I still marvel at those beat-up Bushnells—the same pair he was photographed with back in the 60s. He told me he had been given a better pair, but he usually kept them on a shelf. Why risk them getting lost or stolen when his trusty old pair was still working fine? He had better things to spend money on.

He told me that he could live perfectly comfortably on his government salary, and had donated every penny he’d earned from that huge-selling Golden Guide to support research and, especially, young researchers there in Guatemala and other Latin American countries, to ensure the future of conservation of the birds he loved. Most of us had coffee after lunch, but not Chandler Robbins. He told me he loved coffee but tried never to drink more than a cup a day because the natural habitat where coffee could be grown was so precious.

I mentioned to him that my hearing wasn’t as good as it used to be, and he told me to get hearing aids. He said even his younger brother Sam, considered to have the best ears in all of Wisconsin back when I met him in the 70s, had finally swallowed his pride and bought a pair, thanks to five Winter Wrens that Chandler could hear wearing his hearing aids that Sam couldn’t hear at all. Now when I hear Winter Wrens as clear as tinkling bells through my own hearing aids, I think of Chandler Robbins.

I think it was in Guatemala that I told Chandler Robbins how fixated I’d become on the Cuban Tody, and how badly I yearned to see one. That was of course back when travel to Cuba was highly restricted. This straight-laced, life-long federal employee laughed and said, “Well, Laura, all you have to do is drive up to Thunder Bay and fly from there. You don’t have to worry—they won’t stamp your passport.” Someone who had done all the research throughout Latin America that Chandler Robbins had apparently knew just how to deal with bureaucracy and red tape, at least when it came to birds.

In one of our meetings, I learned that he grew up in Boston and majored in physics at Harvard, where he actually knew John Kennedy, a year or so ahead of him. After college, he became a high school science teacher until the war. Chandler grew up in a religious family—his brother Sam was a minister, and he himself was a conscientious objector. Because he couldn’t serve in the military, he was assigned to clear debris from blocked roadways in national forest land in New England. Then in 1943, he got an opportunity to start banding birds at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, where he soon became a junior biologist with the US Fish and Wildlife Service, setting the course for his life's work.

In the early 1950s, Chandler Robbins learned that the Naval Air Station Midway, out on the Pacific on Midway Island, which had been decommissioned in 1950, was re-commissioned in the face of the Korean War. At that point, with planned jet aircraft take-offs and landings for the first time on the island, the military thought it best to exterminate the nesting albatrosses to avoid collisions. Robbins and some of his colleagues thought if scientists could figure out what vegetation the albatrosses preferred, what substrates they avoided, and their patterns for takeoffs and landings, they could perhaps set the runways where the birds wouldn’t affect safety. That was back in the olden days when different government agencies actually worked together to find the wisest long-term solutions for everyone concerned.

So on December 10, 1956, Robbins caught and banded 99 adult albatrosses as they were incubating eggs—they’re quite clumsy on land, so they weren’t all that hard to catch. He put band number 587-51945 on one bird. Those leg bands are sturdy, but affixed to the leg of a bird flying about 50,000 miles low over salt water every single year, they get corroded and wear out. Some birds probably lost their bands altogether, but this particular one was re-trapped five times while her leg band was still legible. Each time the worn out band was removed and a new one put on. Each time, the old number was recorded along with information about the bird’s condition and the new band number. All this data was recorded on cards—banding data wouldn't be computerized for decades.

Bird-banding recaptures happen infrequently, bands are replaced even more infrequently, and replaced bands are virtually never replaced again, so when banding data started being computerized, the system wasn’t programmed to track backwards through such a long line of replacement bands. It was Chandler Robbins himself who started wondering about how far back any birds with replacement bands could be tracked. He’s the one who in 2011 looked at an albatross with a bright red plastic band, number Z333, and dug into the data to find out what her previous band was numbered, and the one before that, and the one before that, to realize this particular albatross was one of the ones he had banded on his first trip to Midway Island! I don’t know if anyone has dug into the data to see if others from that cohort are still alive. As I said, worn bands grow illegible or even wear off entirely, and birds in that situation would be impossible to recognize now.

That particular albatross, who made international news in 2011 as the world's oldest known wild bird, was given the name "Wisdom." This year, she is still alive, and still nesting. Her egg hatched last month. This bird, once condemned to die an anonymous victim of progress, was a mother once again, thanks to the soft-spoken hero who helped find a way for birds and jet aircraft to peacefully coexist.

Of all the wonderful people I’ve known during my six and a half decades of life, Chandler Robbins has been my North Star: the person I’ve tried hardest to emulate in every way, for his generosity of spirit and his gentle, unassuming manner belying the brilliance of his work. He lived his life in service to others, including the birds he loved. He was like a chickadee—working hard, staying near and dear to his family as he also served quietly as a leader of his flock. If he knew he was the one doing the most work, and the most important work, he never let on even as he kept on doing that work long after he officially retired in 2005. In 2015, at the age of 97, he was still going to work at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center a few times a week. He explained his long career and continued dedication to his work: "When a lot is expected of you, you do as much as you can to squeeze it all in."

Yesterday I learned that the man whose book guided me every step of the way through my first years of birding, the man whose conservation work ensured that there would still be a wealth of birds for me to enjoy today, the man who has been my North Star since I first met him almost 40 years ago and who I most deeply associate with bird song because he dedicated his life to ensuring that springs would never be silent—this beloved man had passed away on the first day of spring. I picture him and Rachel Carson looking down and praying that somewhere here on earth, someone has the humility and courage to keep their legacy alive.