On Saturday morning, in advance of a big snowstorm, my friend Erik Bruhnke and I drove to Superior, Wisconsin, to see a small group of Eurasian Tree Sparrows that have been hanging out in one neighborhood since December. Four birds were originally reported by DeAnna Leino on Dec 20, 2022, and since then, many birders have found up to three. I badly wanted to see them—the birds are winsome and cute, belong to a fascinating species, and are over 600 miles from the species’ established range in America, to say nothing of the fact that they’d be new for my Wisconsin list.

Like their close relative the House Sparrow, Eurasian Tree Sparrows were introduced to North America long ago, but unlike their bigger, more aggressive cousin, the only place a breeding population became established was in the vicinity of St. Louis, Missouri. By the 1970s, they were also being found regularly around Cahokia Mounds State Park in Illinois—one of my dear birding friends, Randy Korotev, was one of the people studying their range expansion there. Once in a while, one would stray up to Iowa or southernmost Wisconsin, too, but that was pretty much that until around the turn of the century. Now the birds seem to be expanding in all directions, with eBird reports from as far west as British Columbia, north up to central Alberta, and east to Nova Scotia.

In my neck of the woods people have seen strays in Two Harbors and Duluth, but so far, the birds appearing so far out of their typical range seem to be wanderers who stick around for just days, weeks, or a single season, so most birders still add them to their life list in St. Louis, where I saw my lifer in 2004.

I’ve seen them there multiple times since, especially at my friend Susan Eaton’s place.

In 2014, I saw them within their natural range in Austria and Hungary.

2015, I saw some at a distance in southern Illinois during an unsuccessful attempt to see an Ivory Gull. Not too bad of a consolation prize!

In winter 2017, a Eurasian Tree Sparrow was found hanging out by the Do North Pizza Parlor in Two Harbors.

Last spring, one visited Scott Wolff’s place on Park Point. I got to see both of those Minnesota birds.

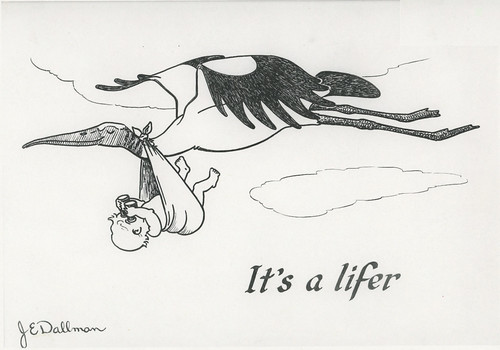

Erik Bruhnke is a professional bird guide for Victor Emanuel Nature Tours who has taken birders to many destinations in North, Central, and South America and Hawaii, but he’s never visited the St. Louis area. And because he spends so much time in far-flung places, he wasn’t in town when the Two Harbors or Duluth birds showed up. This Superior bird would be a lifer for him.

And so Saturday morning, armed with our binoculars, cameras, and cups of Bird Friendly coffee, we set out at 7:30 knowing the snow was supposed to start at 9. When we arrived near the two backyards and alley where the tree sparrows were supposed to be hanging out, we didn't see anything except pigeons, but en route, I’d noticed a large flock of House Sparrows at a feeder a couple of blocks away, so we strolled around the neighborhood, checking out that feeder and all the juniper and cedar-type trees where sparrows like to roost. After an hour and a half or so, we warmed up with a donut break at a cool shop called A Dozen Excuses, where I got a cherry-filled turnover and Erik got a raspberry-filled donut. Yum!

When we got back to our birding spot, someone else was pulling up—one of northern Wisconsin’s top birders, Robbye Johnson. We spent several minutes chatting as we scanned, but again no luck. When Robbye went on her way, Erik and I moseyed around the neighborhood one last time. I listened to a clock tower chime 11 times as the wind picked up and tiny snowflakes started to fall—excellent reminders that we'd lucked out so far, at least weather-wise, but didn’t have much time. This time, when we worked our way back to where the birds were supposed to be, voila! Erik got a great photo of one pretty much out in the open.

|

| Photo by Erik Bruhnke, Copyright 2023 by Erik Bruhnke. |

I saw but couldn’t get my camera on that one, so my own best shots were from an entirely different vantage point, of one of the birds tucked in a white-cedar.

We quickly spotted a second bird deeper in the tree, and as we watched for 5 or 10 minutes, we finally got glimpses of the third, staying even deeper in the tree. Two of the birds moved lower and flitted out a couple of times to grab morsels at a feeder close to an owl decoy.

Now it was clearly time to head home. We made it back just before the serious snow started falling.

Seeing these birds was ever so satisfying, far beyond being additions to our birding lists and photo collections. I’ll treasure my photos, but even more the picture in my mind’s eye of these plucky little outliers, so lovely, fluffed out against the wind, dealing so beautifully with this exceptionally long winter. I don’t know how long they’ll remain in Superior, or whether a breeding pair might form and stick around, but spending a little time with them just before the oncoming blizzard was the perfect way to warm our hearts.