|

| Flaco, the escaped Eurasian Eagle-Owl in Central Park, NY. Photo by Rhododendrites, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons |

I recently received an email from podcast listener David McArthur from New York, who writes:

As you may have heard, a Eurasian Owl named Flaco has escaped into Central Park. He is now living wild in the woods across from my house. I saw him yesterday and I am wondering whether it would be legitimate to include him on my life list. Thank you in advance for your expert adjudication.

I guess I AM sort of an expert in what is “countable” or not, because in 2013 I did a Big Year for the Lower 48, trying to see as many birds as possible during that calendar year. The American Birding Association sets the official rules for Big Year totals so any birder’s Big Year numbers can be fairly compared to anyone else’s. The final total of species I saw in the wild was 604, but only 593 of them were “countable” by ABA rules at the time. I'm perfectly happy telling people I saw over 600 species that year, but always with the explanation that that was my personal total, and that my ABA total—the one that counts for any fair comparison with anyone else's total—is just 593.

Nine of the "uncountable" species I saw in 2013 were introduced species that hadn't yet established a naturalized population as defined by various state ornithological societies. Two were native endangered species that had been reintroduced but still required active intervention. Even now people are monitoring California Condors, providing safe food sources, and occasionally recapturing birds who show signs of lead poisoning. In 2013, people were still providing nest platforms for Aplomado Falcons in south Texas.

But that rule was changed a year or two later to this:

An individual of a reintroduced indigenous species may be counted if it is part of a population that has successfully hatched young in the wild or when it is not possible to reasonably separate the reintroduced individual from a wild-born individual.

That rule was retroactive as far as state and life lists go, and since both condors and Aplomado Falcons were breeding successfully in the wild in 2013, they're on my official ABA life list, but rule changes are not retroactive as far as Big Year totals go. Those numbers only have meaning if everyone doing a Big Year follows the same rules. I made a special effort to see condors and Aplomado Falcons because of my personal focus on conservation. From a competitive birding standpoint, it wouldn’t be fair if my total for the year jumped with the rule change when other people doing Big Years in 2013 had no reason to look for what were uncountable birds.

ABA rules allow us to count birds only if they're on the official checklist where we saw the bird. Vagrants, such as the Rufous-necked Wood-Rail I saw at Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge during that Big Year, may not be on an official list yet when birders flock to see it, but as soon as that state’s records committee makes the determination that the bird almost certainly got there on its own, that bird does become countable retroactively. So those of us who did a Big Year in 2013 and went to Bosque at the right time listed the wood-rail “provisionally” until it became official when the New Mexico records committee voted in favor of it the following year.

Rules for Big Year and ABA lists are strict, but there are no rules for counting whatever we want on our personal lists, including our life list. eBird reports of the Central Park Eurasian Eagle-Owl are flagged “exotic escapee." If I lived near New York, I’d still do my best to see and photograph it and report it on eBird in the same way I put Chukar on my eBird list after seeing a group in my own neighborhood. Like the eagle owl, the Chukars apparently escaped from a game farm and are not countable on any official Minnesota list, but it's still worth keeping track of escaped birds just in case some eventually do end up breeding in the Upper Midwest, as they already do in the West.

A few years ago, David McArthur saw a little flock of Helmeted Guineafowl on a country road in Upstate New York. Like my Chukars, those had clearly escaped from captivity. I’ve got Helmeted Guineafowl on my own life list because I saw them in the wild in Uganda in 2016.

They’re native to Africa, but they’ve also been introduced in the West Indies, Brazil, Australia and southern France. They’ve never been introduced in America, though many aviculturists keep them in aviaries and on game farms. I saw and photographed a small flock in Port Wing, Wisconsin, in 2021, but did not list them on eBird—even though they weren't in any enclosure, they belonged to people who have a lot of exotic animals, and seeing them didn't feel all that exciting. If I see them again, especially if they wander to another property, I'll list them on eBird, not that they'd be “countable,” but like my Chukars, reports could provide valuable datapoints if escaped birds ever do start breeding in the U.S.

The likelihood of David’s Eurasian Eagle-Owl starting a naturalized population is not just remote—it's impossible without any eagle owls in the wild to mate with. But if the species ever did become established anywhere in North America, or if the New York City owl mated with a Great Horned Owl and produced hybrid young, it would be valuable to know when the first individuals appeared. More important in the here and now, keeping track of this individual is essential for all kinds of conservation reasons in a city where rat poison and many other urban dangers are so prevalent.

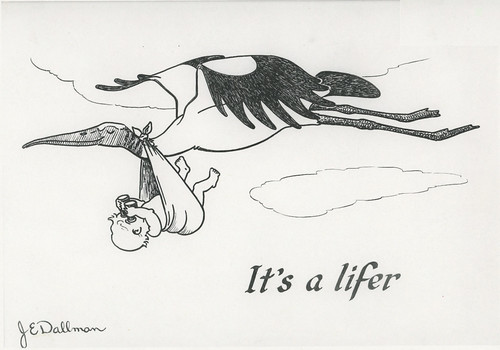

Beyond that, I'd relish a chance to see the species that delivered all those sweets to Draco Malfoy his first year at Hogwarts. If I saw Flaco, the memory would be more vivid and exciting than the memory of a lot of my countable lifers. He may not be a legitimate twitch on anyone's "official" lists, but based on the number of people thrilled to be seeing him right now, Flaco has earned an honored place on a lot of people's life lists of avian treasures. And isn't that what a life list is all about?