From the time I was a very little girl, I wondered about bird tongues. Well, actually, I wondered about all tongues. Dog tongues lolled out, dripping with saliva. Cat tongues were scratchy and much drier. My tongue was a big fleshy blob in my mouth and, if I tried paying attention to how it worked, I always ended up biting it. And every time I bit my own tongue, I wondered how birds could possibly

not bite their tongues with those pointy, sharp-edged beaks. As I got older, I started figuring out that their tongue might be narrow—maybe even pointed—to fit into their beak, but it still seemed like it would be awful on the occasions when a bird did bite its tongue.

|

Ruby-throated Hummingbird showing off her tongue.

|

I learned in elementary school science that mammals have taste buds on our tongues. In college, we learned that the tongues of birds are simple structures without the important refinements of mammal tongues, and are virtually devoid of taste buds, so birds have a poorly developed sense of taste, or none at all. Anyone with any insight at all could observe feeding birds making choices based on taste, but they were pooh-poohed by the professionals who could see clearly under the microscope that virtually all bird tongues are, indeed, lacking taste buds. James Rennie wrote, bravely but somewhat hesitatingly, in

The Faculties of Birds in 1835:

These facts and many more of a similar kind... fully authorize us, we think, to conclude, that some birds at least are endowed with the faculty of taste; though this is expressly or partially denied by certain authors distinguished for accuracy of observation.

Rennie was right, though it took a long time to establish how, exactly, birds can taste without taste buds on their tongues. In ducks, large numbers of taste buds are found on the tips of the beak, four clusters on the upper and one on the lower, where the food first comes in contact with the mouth. In many birds, the taste buds appear to be located near the salivary glands. This needs a lot more research, but since this blog post is about the tongue, we'll leave taste out of the equation.

|

| The inner surfaces of Mallard bills have five major clusters of taste buds. |

Tongues of all animals—mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs, and others—are intriguing structures. (I recommend

Wikipedia’s article about them ). The tongue, like an elephant’s trunk and a few other boneless muscular structures that are used to manipulate items or move an animal around, is called a muscular hydrostat. (Check out

Wikipedia’s article about muscular hydrostats ). These intriguing structures work, in large part, by having two or more sets of paired muscles, one along the length of the tongue, one across the width, and sometimes one or two running diagonally. Muscles work by contracting. When a muscle fiber is relaxed, it reaches its full length and narrowest width, and when it’s working, it pulls in to be shorter and thicker. The muscles of a muscular hydrostat work together, contracting and expanding, to give the animal control over the structure.

But a muscular hydrostat isn't enough for a complex organ like a bird tongue. In all higher vertebrates (including us!)

the tongue is supported by a cartilage-and-bone Y-shaped structure called the hyoid apparatus. In birds, that hyoid apparatus is most exquisitely, and weirdly, developed in woodpeckers and hummingbirds, especially those species that stick their tongues out far beyond the tip of their beaks.

Hyoid bones rest inside a sheath that keeps them lubricated and allows them to slide forward somewhat as the tongue is extended. The base of the hyoid bone (the bottom branch of the Y) extends all the way to the tip of the muscular tongue. The Y forks just in front of the throat, where most of the muscles controlling the hyoid attach. The two horns of the hyoid grow backwards from this area toward the base of the skull, and when they are fully grown, the sheath around them fuses with the skull. Special muscles that originated on the lower jaw attach at the fork of the hyoid to control the tongue. The hyoid horns of some species of woodpeckers are amazingly long, and can grow all the way around the back of the skull up to the top and, in some species, even above the eye socket. Some even extend into the nasal cavity!

When a baby woodpecker hatches, the hyoid bones are still quite short, not reaching much beyond the base of the skull. A large tongue could get in the way when woodpecker nestlings and young fledglings are being fed by their parents, because they wrap their bill around the parents' bill as the adults regurgitate food into their mouth. I don't have a photo of that, but do have one of me feeding a flicker nestling so you can at least get an idea of how the young woodpecker's mouth works.

|

| At this point, the hyoid apparatus isn't fully developed, when a longer tongue would just get in the way anyway. |

As the hyoid bone grows, the woodpecker can extend the tongue farther and farther out. In flickers, it will eventually be able to protrude VERY far!

|

| Left: The tongue of a short-tongued woodpecker such as a sapsucker, at rest and protruded. Right: The tongue of a long-tongued woodpecker such as a flicker, at rest and protruded. Notice how much longer the branched horns (in red) of the hyoid are in order to allow it to stick the tongue out so far. This is from a great website debunking anti-evolution groups, the TalkOrigins Archive, which has the best explanation of the hyoid apparatus I've ever read. |

A woodpecker or hummingbird’s tongue is as short and wide as it gets when the lateral muscles of the muscle hydrostat are relaxed and the horns of the hyoid bones are pulled all the way into the sheath. That’s when the tongue easily fits within the closed beak, with no risk of the bird biting it.

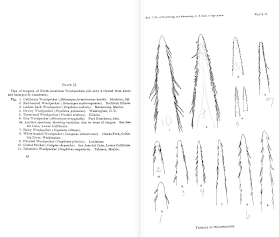

Here are some illustrations of the upper surface of woodpecker tongues (up to where the hyoid apparatus branches) from

F.A. Lucas's1895 monograph, The Tongues of Woodpeckers, for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Division of Ornithology and Mammalogy.

Here is an illustration of the hyoid apparatus (showing just one full branch of the horns each) for an adult and a young flicker and an adult sapsucker. There are also illustrations of the surface of the tongue as it develops in some species.

The tips of many bird tongues have specialized functions, making them even more complex and fascinating. Researchers of one study published in

The Auk (Pascal Villard and Jacques Cuisin, How do woodpeckers extract grubs with their tongues? A study of the Guadeloupe Woodpecker [

Melanerpes herminieri] in the French West Indies. The Auk 121(2):509-514. 2004) found that "the Guadeloupe Woodpecker does not spear grubs with its tongue but instead grabs them with the tongue's horny tip, which is barbed and coated with saliva, and pulls them out of the holes."

Flickers have a sticky tongue with a barb at the tip—when a flicker probes the subterranean tunnels of an anthill, a dozen or more ants may adhere to the surface each time the bird pulls in its tongue thanks to the stickiness. But flickers do not live by ants alone. When one hears an insect in the wood of a tree, it can hammer with its bill to make a hole down to the bug, and not have to widen the hole at all—once it exposes the tasty morsel, it can pull back its head and stick in just the thin little tongue to grab the grub and pull it in. Without that extrusive tongue, it would have to make the hole significantly larger in order to probe it with the bill open like a forceps. The tongue allows it to save time and get a higher percentage of food items, since every minute spent hacking into a tree provides more opportunities for a dangerous situation to force the woodpecker to fly off without the meal. I've never taken a photo of a woodpecker's tongue fully extended, but have a few with the tongue out at least a little:

|

| Northern Flicker (Red-shafted) |

|

| Red-bellied Woodpecker |

|

| Pileated Woodpecker |

As a birder, whenever I got a momentary glimpse at a bird’s tongue, I was thrilled. But it wasn’t until I started taking pictures that I could get more than a quick look. Some tongues are wonderfully cool to see, especially when you understand enough of the bird’s behavior and diet to make sense of how that species’ tongue evolved. Others seem rather simple. Canada Geese have a human-looking tongue, or, really, one like a grazing mammal’s, because geese are also grazers.

|

| This Canada Goose disapproves of photographers |

The serrations on their bill help them to rip into and pull grass. Geese don’t have teeth, of course, so can’t chew a cud to break down the silica-infused cell walls of grasses to make them more digestible, and as flying creatures, they can’t lug around a heavy cow-like stomach. So geese may eat grass but aren’t efficient at digesting it, as the slippery ground anywhere near a goose feeding area can attest. Their tongue, like ours, simply helps get food from the forward parts of the mouth to the throat.

|

| You can see the bill serrations on this preening goose. This photo would also serve to discuss feathered eyelids, but that's for another blog post. |

I’ve not had the luck to ever see or get a photo of a duck’s tongue, but I know that many ducks have extraordinarily bizarre tongues, useful for holding in and swallowing food while straining out water and tiny mud particles.

|

| The huge, bizarre tongue in the middle is that of a Cinnamon Teal! The complex one on the upper right is that of a Red-breasted Merganser. From Leon Gardner's 1925 monograph cited below. |

Fortunately, I at least have illustrations of those thanks to a wonderful monograph about bird tongues that I found at a book sale at an ornithological meeting.

The Adaptive Modifications and the Taxonomic Value of the Tongue in Birds, by Leon Gardner of the United States Army Medical Corps, was published as part of

The Proceedings of the United States Museum in 1925, back when the U.S. government was sincerely focused on science. I managed to get a copy, discarded from the University of British Columbia library, at an AOU meeting back in the 90s. In Gardner’s introduction, he writes:

As is well known the tongue is an exceptionally variable organ in the Class Aves, as is to be expected from the fact that it is so intimately related with the birds’ most important problem, that of obtaining food. For this function it must serve as a probe or spear (woodpeckers and nuthatches), a sieve (ducks), a capillary tube (sunbirds and hummers), a brush (Trichoglossidae [a former taxonomic group for the honey parrots, or lorikeets]), a rasp (vultures, hawks, and owls), as a barbed organ to hold slippery prey (penguins), as a finger (parrots and sparrows), and perhaps as a tactile organ in long-billed birds, such as sandpipers, herons, and the like.

Many of the unique differences among bird tongues have to do with special adaptations of the tip. Woodpeckers, except sapsuckers, have a stiffened barb at the tip. Birds that drink nectar tend to have brushy tips to increase the amount of nectar they can take in.

Hummingbird tongues pull in the fluid in two different ways. Capillary action, the fluid drawn up in grooves along the narrow tongue structure, enhanced by the way the tip of the tongue is split, broadened, and brushy, is probably the less important. The simple act of lapping up the fluid (as well as gulping!) probably brings in a lot more. While feeding, the tongue extends and contracts rapidly—up to 13 times per second. And the two tips sort of cup up to maximize the amount of fluid in each gulp. Even though some hummingbird tongues are partly rolled, rather like a microscopic coffee stirrer, the hummer never “sucks” up the fluid. Russ Thompson's amazing YouTube video shows hummingbird tongue action as well as you're ever going to see it.

Sapsuckers, like hummingbirds, specialize on fluids, and the brushy tip to the tongue allows them to collect more fluid each time their tongue protrudes into a sap well. Cape May Warblers also feed on fluids, visiting sapsucker drill holes and also sometimes bird feeders with jelly or sugar water. And sure enough, unlike most warblers, their tongue has a brushy tip.

|

| Yes! My brushy tongue does help me lap up sugar water! |

|

| The tongues of six nectar or fruit-eating birds. 1. American Robin. 2. Cape May Warbler. 3. Venezuelan Troupial (same genus as many of our orioles).4. Green Honeycreeper. 5. Bananaquit. 6. Micronesian Myzomela (a honeyeater). |

When I became a bird rehabber, I got my first opportunities to look carefully into the mouths of living birds. When I fed baby Blue Jays and robins, I could see that the tip of their tongue—what looks to us like the main surface—is shaped like an arrow, allowing it to neatly rest on the floor of the lower bill. That tip rests on the muscular hydrostat--the main tongue, which looks like a muscular stalk rooted to the floor of the mouth. That stalk controls the tongue to manipulate food items and then, when swallowing a large item such as a fruit, the bird can lift the widened back part of the arrow-like tip to help it pull the food item to the back of the mouth and down the hatch.

I took the following photos at the Reifel Migratory Bird Sanctuary in Vancouver this fall, on a dim, rainy day, so the photos are very grainy and poor, but oh, well. You can see the "arrowhead" tongue tip, and a bit of the supporting "stalk" (the main, muscular part of the tongue) below. The tiny spines on the surface of the roof of the mouth point in, helping keep the berry or crabapple from moving forward.

|

| Here you can see the flat "arrowhead" tongue tip. Where it rests on the main, muscular tongue is a little obscure but visible. |

|

| See the spiny roof of the mouth that keeps the fruit from moving forward as the robin works it down. |

|

| Now you can see the whole "arrowhead" |

|

| From this angle you can see the muscular tongue holding up the arrowhead. The wide part of the tongue tip, along with the muscular base, pushes the fruit down the hatch. |

|

| Keep pushing! |

|

| Almost down the hatch! |

|

| Yum! |

Waxwings swallow fruit in the same way.

|

| You can see the supporting "stalk" or muscular part of the tongue supporting the tip. |

|

| Same thing from another angle |

Not all birds need to manipulate their food with a tongue, and for some of them, any normal tongue would get in the way. Swallows and nightjars fly into most food items at high speed, their food going straight down the hatch. Swallows use their tongue for manipulating nest materials and, in some cases, eating other items, so although it’s somewhat reduced, their tongue is still functional. But nightjars use their feet to scrape out a little nest spot on the ground, and eat nothing more than flying insects. Their tongue is nothing more than a tiny vestigial flap in the back of the mouth.

|

| "Fred the education nighthawk" His tongue is just a tiny flap that you can't see from this angle. |

Birds that gulp fish down whole, such as loons, herons, and pelicans, need their tongue to get out of the way while swallowing.

|

| The tongue is just that thickened blob at the base of the throat--the rest is all pouch! |

|

| The gray tip of the tongue and pink fleshier area with side "horns" is the forward part of the tongue, attached to the most muscular area. The little processes that we can see are not related to the hyoid, but are simply part of the complex tongue shape that allows it to use the tongue for manipulating nesting materials and manipulating fish to swallow them head first. |

Most birds that carry fish back to the nest to feed their young use their feet to carry one fish at a time (like Bald Eagles and Osprey), or eat the fish first and regurgitate them to their young (like herons). Herons can regurgitate a dozen fish or more onto the nest floor for their young to grab. Terns can easily carry one small fish at a time back to the nest. They usually nest on the shoreline fairly close to good fishing areas.

Puffins pursue fish many miles from the nest. They don’t regurgitate food, and can’t manage very large fish, so in order to provide enough food for their young, they must carry as many fish at a time as possible. The normal catch is about a dozen fish per trip, but Audubon’s Project Puffin website cites a record-breaking puffin carrying 62 fish in Great Britain! (I wish I had a photo of a puffin carrying fish.)

It’s fascinating to see puffins flying with so many fish, and even more thrilling to realize that they caught them one by one. How is it possible to catch a fish when you already have 5 or 10 in your beak? Puffins have several important mouth adaptations to accomplish this amazing feat. First, the soft gape where the upper and lower mandibles join is stretchable, allowing the edges of the bill to be parallel even when holding fish. The ability to hold the bill edges parallel and the strong hook at the front of the bill keep fish from getting sliced or falling out. When a puffin catches the first fish, it holds its specially adapted, slightly spiny muscular tongue against the roof of the mouth, which bears longer spines pointed backward to hold the fish in place as it catches the second, and then the third, and on and on. That muscular tongue is just the right tool, working with the specialized bill and the perfectly appointed roof of the mouth.

|

| The perfectly appointed puffin! |

Here are some random photos of other bird tongues:

|

| Condors use their muscular, somewhat raspy tongue to shovel blobs of dead animals down the hatch. In other words, they use their tongue much as we humans use ours. |

|

| Gray Jays have amazing salivary glands that can coat meat that they cache with a gluey saliva, protecting it from decaying. Their tongue helps them swallow food, push food into their throat pouch, or retrieve the food out of that pouch. |

|

| Nuthatches use the noticeably barbed tip of the tongue to probe into tree crevices. |

I got my greatest insights into bird tongues, in a most visceral sense, when I rehabbed a fledgling Pileated Woodpecker. That's when I learned not just how long their tongue is, but how they use it to probe about in tunnels, feeling their way where bugs might be. I do not know a single person who got the inside scoop on Pileated Woodpecker tongues the way I did, but this was in the 1990s before I was doing much photography, so you'll have to take my word on this. My little Gepetto liked to sit on my arm, his beak inches from my ear, and stick his tongue right in, running it around every fold. I don’t know if he was optimistically rooting around for grubs, curious about ears that stick out so bizarrely and un-aerodynamically, practicing his tongue technique, or what, but I’m still the only person I’ve ever known who was French-kissed in the ear by a Pileated Woodpecker.

|

| Even young boys know better than to let a Pileated Woodpecker within reach of their ears. This is Gepetto, but my son Tommy is wisely keeping his distance. |