Before every trip I’ve ever made to a new country, or a new

state, a new wildlife refuge, a new garbage dump, or just about any other new

place, I’ve always speculated about what the very first bird I’d see would be. I

knew my first Peruvian bird would not be an Andean Cock-of-the-rock, a

Marvelous Spatuletail, or an Andean Condor. It was equally unlikely to be a

toucan or trogon. One of the common hummingbirds wasn’t entirely out of the question, but I

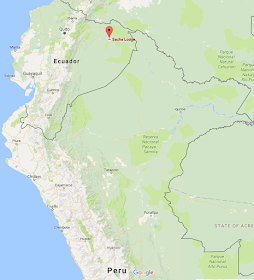

arrived in Lima at midnight, spent that night in a hotel right across the

street from the airport entrance, and had an early morning flight to northern

Peru, so my first bird was obviously going to be an urban species.

Sure enough, the first birds I saw in Peru were on the tarmac at the airport in Lima. They weren’t House Sparrows, Starlings, or Rock Pigeons, the species I most often see at airports, and they also weren’t any of the gulls, though the likely gulls in Lima were species that would have been lifers. No, the very first species I saw in Peru was, appropriately enough, the West Peruvian Dove. I got a quick look before it flew off, so I'm sure that's what I saw—it had a plain back and a distinctive white edge to the wing. A few minutes later we found doves again, and I took some crappy photos through the window as we waited for our flight, but I was thrilled—pictures of my first LIFER in Peru!

Sure enough, the first birds I saw in Peru were on the tarmac at the airport in Lima. They weren’t House Sparrows, Starlings, or Rock Pigeons, the species I most often see at airports, and they also weren’t any of the gulls, though the likely gulls in Lima were species that would have been lifers. No, the very first species I saw in Peru was, appropriately enough, the West Peruvian Dove. I got a quick look before it flew off, so I'm sure that's what I saw—it had a plain back and a distinctive white edge to the wing. A few minutes later we found doves again, and I took some crappy photos through the window as we waited for our flight, but I was thrilled—pictures of my first LIFER in Peru!

Unfortunately, when I got home and studied the pictures, I could clearly see little dark markings on the back and on the face that made the photographed birds Eared Doves—not a lifer at all! I'd already seen that species in Ecuador in 2006. I'm still certain that the first bird I saw at the airport was a West Peruvian Dove, and I saw plenty more later that day and the next, but am both disappointed that I don't have a photo of my lifer and disconcerted that I misidentified the Eared Doves in my photos.

If I’d gone to Peru any time before 1997, the West Peruvian Dove would not have been a lifer—it used to be considered a population of our own White-winged Dove, which I’d first seen in Texas back in the 70s, and have since seen in Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Florida, and Kansas, as well as in Mexico, Guatemala, and Costa Rica.

If I’d gone to Peru any time before 1997, the West Peruvian Dove would not have been a lifer—it used to be considered a population of our own White-winged Dove, which I’d first seen in Texas back in the 70s, and have since seen in Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Florida, and Kansas, as well as in Mexico, Guatemala, and Costa Rica.

The ones in Central America remain in the same species as the White-winged Dove, but those of the Pacific lowlands from southwestern Ecuador south to northern Chile were split into a separate species based on their song, some morphological differences, and mitochondrial DNA. The species is also called the Pacific Dove and, in Peru, the cuculí for its lovely and distinctive song.

Living up to the name, we only saw West Peruvian Doves on our first and second days in Peru, when we were in the lowlands west of the Andes, and our final morning in downtown Lima. Like our White-winged Dove, the West Peruvian Dove has adapted well to urban life, so it was very easy to see right in the city. That final morning, back in Lima after six spectacular and full days of birding, we strolled a quarter mile or so from our downtown hotel to an urban park overlooking the coast. From there, I added nine more lifers—Red-legged Cormorant, Peruvian Pelican, Peruvian Booby, Blackish Oystercatcher, Belcher’s, Gray-hooded, Gray, and Kelp Gulls, and Inca Tern. Those birds were all distant, and it was difficult and frustrating trying to get identifiable photographs of at least some of them in the low morning light. But two other birds, both lifers on our first day—the Scrub Blackbird and West Peruvian Dove—spent the entire time we were there walking about just a few feet from us. I took about 450 photos that morning, but the best ones were of those two nearby birds, and the last bird photos I took in Peru were of that one confiding West Peruvian Dove in downtown Lima.

Information about the species is pretty sparse: the Cornell

Lab of Ornithology’s Neotropical Birds website has nothing at all about its

behavior or much else except noting that it’s expanding its range south thanks

to being so well adapted to agriculture and urbanization, so some individuals are

now being reported as far south as Santiago and some have crossed the Andes to

northwest Argentina. The authors speculate that this dove may spread in arid

zones throughout the southern cone of South America.

Cornell makes it easy for birders and ornithologists to upload information, photos, and recordings about Neotropical birds, as does Wikipedia, but I suspect that most people working or birding in the tropics feel more urgency to focus their attentions in habitats and on species that are more vulnerable. The West Peruvian Dove is common and increasing, so easy to overlook, as even I noticed when I was taking hundreds of pictures of distant lifers but just a handful of the beautiful dove right in front of me—one that had been a lifer just six days before! Even though I did not pay it the attention it deserved, it stuck around me more than I deserved. I’m very grateful that the beautiful little dove that was my first Peruvian bird was also my last.

Cornell makes it easy for birders and ornithologists to upload information, photos, and recordings about Neotropical birds, as does Wikipedia, but I suspect that most people working or birding in the tropics feel more urgency to focus their attentions in habitats and on species that are more vulnerable. The West Peruvian Dove is common and increasing, so easy to overlook, as even I noticed when I was taking hundreds of pictures of distant lifers but just a handful of the beautiful dove right in front of me—one that had been a lifer just six days before! Even though I did not pay it the attention it deserved, it stuck around me more than I deserved. I’m very grateful that the beautiful little dove that was my first Peruvian bird was also my last.