One of the most peculiar of all the birds in the world is also

one of the coolest. The pheasant-sized Hoatzin, a bird of the swamps, riparian

forests, and mangroves of the Amazon and the Orinoco Delta in South America, is

the only species in the family Opisthocomidae, named for the Greek, “Wearing

long hair behind,” referring to the long feathers that form its funky, loose

crest.

But where this unique family falls in relation to other

birds is still disputed. Right now, the checklist the Cornell Lab of

Ornithology uses places it in the order with cuckoos and roadrunners, but all

kinds of factors, including DNA, keep this under dispute. Some taxonomists

place it as the only member of a unique order, but even they aren’t sure where

to place that order in relation to other orders. It may be somewhat related to

those cuckoos, or to cranes, or to shorebirds, or to doves. The more evidence

we gather about Hoatzins, the more it contradicts evidence we already had, and

the more confused ornithologists grow.

Hoatzins are unique in several ways. Unlike virtually all

birds, they efficiently digest leaves, which comprise over 80 percent of their

total diet. Leaves are far more difficult to digest than just about anything, including

fruits and seeds, thanks to the cell walls that distinguish leafy plant cells

from animal cells.

Cell walls make leaves, by their very nature, harder to digest

than fruits or, once you get through the outer coating or shell, seeds, or any

part of animals. Mammals that digest grasses or other leaves have

specializations. Those rodents that feed on grasses have special grinding

molars; larger mammals that feed on this plant matter digest it through

fermentation. Ruminants such as cows, sheep, goats, deer, and giraffes do this

in their foregut, continually regurgitating portions of food called cud that

they chew all over again. Ruminants have a four-chambered stomach.

Hippopotamuses have a three-chambered stomach. Horses, rabbits, and

rhinoceroses have a single-chambered stomach, but an enlarged and

well-developed cecum—an offshoot of the intestines—where fermentation digests

the cellulose. Then the food returns to the intestines to be digested all over

again.

To allow flight, birds require a light digestive system both

in terms of their internal digestive equipment and in terms of passing all

indigestible food out of their systems as quickly as possible. Only a very few

birds, such as turkeys, chickens, and grouse, have well-developed caeca where fermentation

of leafy matter or woody buds takes place, and these birds have large bodies

and fairly limited, short-distance flight. Nighthawks and their relatives also

have well-developed ceca to help them digest the chitin in insect exoskeletons,

but most of the insect matter they eat is more digestible. The anaerobic

bacteria in any bird caeca make droppings that include caecal wastes extremely

smelly.

Geese feed on grass as well as all manner of more easily

digested plant and animal material. But they aren’t specialized for digesting

grass, so most of it goes in one end and comes out the other, which is why

goose droppings are so very noticeable wherever geese are found. People don’t

realize how lucky we are that geese aren’t specialized for digesting all that

grass, or those copious, slippery droppings would also be horrifically smelly.

|

| Baby geese can already digest some leaves, but eat more high-protein bugs at first. |

Unlike all other birds, Hoatzins are specialized for

digesting leaves in their foregut by fermentation, in a way fairly similar to

that of mammalian ruminants. Instead of a multi-chambered stomach, Hoatzins

have an unusually large crop, folded in two chambers, and a large,

multi-chambered lower oesophagus. Their stomach chamber and gizzard are much

smaller than in other birds, but their crop is so large that it displaces the

flight muscles and keel of the sternum, making them extremely poor fliers. Fermentation

in that oversized crop is smelly, giving Hoatzins their nickname, the

stinkbird.

When I was working on my ill-fated Ph.D. studying nighthawk

digestion, I took an avian physiology class in the University of Minnesota’s

College of Veterinary Medicine taught by one of the world authorities in avian

digestion, Gary Duke. Our midterm included a few essay questions, one about

bird digestion. In a bolt of whimsy, I titled my answer, “Alimentary, my dear

Hoatzin,” which tickled Gary’s fancy, so he gave me extra credit, making the Hoatzin even dearer to my heart.

If their digestive system weren’t enough to make Hoatzins

exceptional, they are famous for the two claws that young birds sport on each

wing. These well-developed claws help the awkward youngsters scramble through

trees until they get more coordinated. The claws atrophy and disappear as the

young birds mature.

In the tropics, most slow-flying birds the size of Hoatzins

are endangered thanks to excessive hunting, but Hoatzins have a longstanding

reputation for having bad-tasting meat due to the offensive odor of their

digestive system. They also benefit from living in such wet

habitat—deforestation in their range occurs in upland forests that can support

heavy logging equipment, not the wetlands along the Amazon and its tributaries.

So unlike many tropical birds in their range, Hoatzin numbers remain fairly

strong.

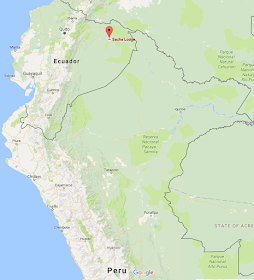

Before this month, I’d seen Hoatzins three times, all in

the area around Sacha Lodge in eastern Ecuador along the Rio Napo, back in February

2006. Hoatzins concentrate in the vegetation overhanging rivers, so we saw them

only from boats. The huge birds stayed within the foliage, and in the unsteady

boats, my only photos turned out to be exceptionally poor.

I was extremely hopeful about seeing Hoatzins in Peru, but we

didn’t get out into any rivers by boat, and were only in Amazonia for one day,

at the very end of the long dry season. Everywhere we were, the water levels

were so low that the shorelines had retreated far from the vegetation. A half-hour

before sunset on our final day, as we rode in our bus back to our lodge after

our final birding spot, our guide explained why we hadn’t seen them on this

trip. We were of course disappointed, but I was still basking in the thrill of

having seen a Marvelous Spatuletail and one species we hadn’t expected but that

I’d desperately wanted to see, the Andean Cock-of-the-rock. I reminded myself that it wasn't like the Hoatzin would have been a lifer. We were talking

about how tricky birder expectations are when one birder glancing out the window saw not just one but a whole flock of Hoatzins!

This was a narrow two-lane road,

but our driver managed to turn the bus around and we piled out. And in the subdued

lighting just before our final sunset in Peru, there they were—at least 20

Hoatzins who didn’t seem to mind getting their photos taken at all! What a

magical way to end the final evening of a magical trip.