|

| The original Li'l Darlin' |

At least two or three times every year, my high school jazz band played a song that I grew to love. It was probably listed in a program or two, but I never noticed what its name was. I last heard it the year I graduated, in 1969, but it’s been stuck in my head ever since as my most beloved and persistent earworm.

My son Tom was in Duluth East High School’s jazz band, but I never heard them play it and it didn’t occur to me to ask Tom if they ever played it in a practice, which was too bad—when I hummed it eight years after he graduated, he immediately recognized it, but he couldn’t remember the name. At least I finally had confirmation that my earworm was an actual song that my brain hadn’t made up whole cloth.

That was ten years ago. And last week, like a lightning bolt out of a clear blue sky, Tom sent me an email with no subject line or text—just a link to a YouTube video. I clicked on it, and there it was—a full 57 years after I first heard the song and 53 years after I last heard it, Count Basie’s orchestra was playing “Li’l Darlin’,” written by Neal Hefti for Basie’s 1958 album, The Atomic Mr. Basie. Note for note, it sounded exactly as I remembered it. How thrilling to hear it again, and to know what it is!

I asked Tom how on earth he’d found it, and he told me that now there are apps that specifically identify songs by humming the tune, and a search on Google can do the same thing when you click the microphone. I was impressed and touched that he remembered the song and how badly I wanted to find out what it was.

An app called Spotify, which has been available since 2006, can identify any recorded song in their database, which has millions of recordings. But if a group does a cover of their own song, with the exact same voices, melody, and instrumentation, Spotify can't identify it unless that exact same version is also in the database.

The algorithms in newer apps such as SoundHound or Google itself not only have a huge database of melodies but can recognize them in perhaps an almost infinite number of combinations of tempos, pitches, and tones, from whistling and humming to scat. Even so, some parts of a song may be more recognizable than others—my son didn’t get a response when he hummed the first two lines of “Li’l Darlin’.” It was only in the next two lines that Google came up with the answer.

As with human dialects, bird songs can vary regionally, and individual birds may sing their own personal tunes. Some species are famous for how many different songs they sing—a single Brown Thrasher is known to have sung 2,400 distinct songs.

To confound bird song ID even more, thrashers, mockingbirds, and starlings very often mimic the songs and calls of other species. And at a given moment, several birds can be singing along with assorted insects, frogs, mammals, and human-generated sounds. If it was tricky for me in my 20s, with excellent hearing, to pinpoint each bird song within the entire surrounding soundtrack, it’s trickier for an app in a cellphone with only a single omnidirectional microphone.

As someone who spent decades desperate to identify a single song, and who spent a lifetime studying bird songs, I appreciate not just how frustrating it is when we don’t recognize something, but how satisfying it is when we do figure it out. Unfortunately, describing bird songs with human words is very hard. If someone uses the word “spiraling” in their description of a northwoods bird, they are usually describing a Veery, and if they whistle a White-throated Sparrow or Black-capped Chickadee song, I can give them the answer just like that, but few bird songs are that easy. Now people often send me recordings made with their cell phone to identify, which would have been very easy before I lost my high frequency hearing, but background noise and the distance between the phone and the calling bird make even some low register songs difficult for me.

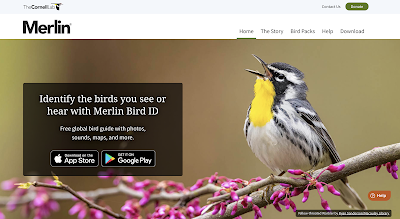

Fortunately, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology has come up with a wonderful bird identification app called Merlin that anyone can use to figure out what birds they’re hearing. Merlin started out identifying birds by description, giving the most likely possibilities for the date and location when you answered a few questions. Then it rose to the next level, identifying bird photos, too, again when it knows the date and location. And now Merlin can also identify birds by sound. When you’re out walking and hear something interesting, you can turn on the app and it will identify, with surprising accuracy, all the birds singing and calling around you. If you’re trying to figure out a Blackburnian Warbler as a robin sings nearby, that doesn’t confound Merlin—it lists them both. Merlin is free, and you can integrate it with eBird so that your sightings will not only satisfy your own curiosity but contribute to the body of citizen science data Cornell is famous for.

So now we can find out what the name of that song is whether it’s produced by a 50s-era big band or an elusive bird singing right that moment, thanks to the wonders of modern technology. From Count Basie to Merlin, how times do change. And, at least in this case, for the better.

|

| Low-tech Merlin |