|

When I was in Bar Harbor, ME, in the presence of all kinds of cool birds,

I couldn't help but photograph this little guy! |

When I was a small child, long before

The Waltons was on television, I used to pretend that I belonged to a happy little family that lived in my neighborhood. Every evening at bedtime, as it grew dark outside, I’d listen to them sharing their stories about their day’s adventures and saying good night to each other. I couldn’t make out their exact words, and they often talked over each other, but I could discern how friendly they were and how jolly their stories were.

My little family was a flock of House Sparrows that roosted in the hedges around our two-flat apartment in Chicago. If I knelt backward on the sofa, I could look out the front room window and see the top of the dense row of bushes. When a sparrow flew in, the bush actually seemed to swallow it whole—one moment the bird was flying fast directly toward the hedge, and a split second later it had completely disappeared, no rustling or shaking of branches or anything. It seemed like genuine magic, which perhaps is why I thought this magical family was half human, half avian, and a hundred percent fairy sprites.

We moved to a working class suburb, Northlake, when I was four. Northlake was all lawns and small Cape Cod houses—no grimy alleys and postage stamp lawns and two-flats and warehouses anywhere I could see. The one factory in town, Automatic Electric, was gigantic, but surrounded by acres of grounds, with manicured lawns and huge trees, and Addison Creek (highly polluted, but we little kids didn't know that!) flowed through it. That factory employed much of Northlake’s population, and was the whole reason our little suburb was built in the first place. And Northlake was noisy, because we were under a flight pattern for O’Hare Airport. But my dad called Northlake “the country,” and it looked like an entirely different world from “the city.”

We had a juniper hedge against our house that the abundant House Sparrows roosted in, so from the day we moved in, I felt a warm sense of familiarity and homeyness. Now at bedtime their little voices seemed to be directly welcoming me into their happy family.

One of the first McDonalds restaurants opened in our neighborhood in the 60s, and I loved going there to feed the House Sparrows. I loved how they looked up at me hopefully, and so enjoyed French fries. One female would come within millimeters of my fingers repeatedly. She wasn’t trusting of me enough to actually alight on my hand, like Briar Rose’s woodland friends in

Sleeping Beauty, but that felt pretty close.

|

| House Sparrows eat fries wherever they find them, including at New York's Central Park Zoo. |

House Sparrow cheepings provided an essential and beloved, ever pervasive element in the soundtrack of my childhood. When I started birding in 1975, after I saw my first chickadee on March 2, all it took was a visit to the East Lansing McDonalds to see the Number 4 species on my lifelist.

That summer, when I took my first field ornithology class, I was overwhelmed by the ornithological treasures I’d never even imagined were all around me—Great Blue Herons, Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, Purple Martins, Scarlet Tanagers, Rose-breasted Grosbeaks. I wrote my final paper in that class, the first scientific paper I ever wrote, comparing the foraging behavior of House Sparrows in two different habitats: the outside picnic table area at a McDonalds restaurant and the area surrounding a picnic table in a back yard. I got an A, but my professor expressed surprise and even some disappointment that of all the birds we’d seen in the course, I chose to write about House Sparrows. But how could this blue collar girl not? I was plagued with a vague fear of abandoning my working class roots and becoming snooty if I abandoned my treasured little sparrows.

|

In a country with Cuban Todies and myriad other amazing birds,

House Sparrows still drew my camera's focus. |

We learned in that class that House Sparrows had been introduced here in America, in multiple introductions for many reasons, including that they were mentioned in the Bible and that people hoped they’d help clean up the horse manure on city streets before Henry Ford came up with a "better idea." I don’t think we learned about the ecological problems they posed, specifically for native cavity-nesting birds because the House Sparrows so aggressively appropriated their nest holes, until I took another ornithology course the next year.

Over time, as I talked to people trying to help Purple Martins and three species of bluebirds, all in dire trouble, I realized House Sparrows really are a horrible problem. But as much as I tried to assume an air of scientific detachment, I couldn’t stifle my warm feelings toward them, at least within the urban environments where bluebirds and Purple Martins are in short supply for a whole variety of reasons that don’t involve House Sparrows. But expressing those warm feelings near anyone involved with protecting native species could just not be done.

Last week I was texting with one of our good family friends about House Sparrows. Scott Melamed, a city kid like me, has grown fascinated with House Sparrows. He wrote:

I really loved seeing them around, in the grass or by homes or wherever. They seemed like a sign of health - that there was this abundance of birds just woven into the city neighborhoods. And it was only in reading about them that I learned about their wild history of invasiveness! ... But they certainly have endured.

I grew up in Plymouth, a suburb of Minneapolis, with lots of birds. I saw far fewer in NYC and DC, but it felt like there was better air when I'd be be out on a walk and see all these sparrows come up from the ground as they do… I still like them, and it's nice to hear you do, too.

Scott’s views are actually mirrored at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, where a wonderful program called

Celebrate Urban Birds (CUBs) is designed to help people living in even the most urban areas to notice and enjoy the birds around them, everywhere from green parks to city sidewalks and apartment balconies and fire escapes.

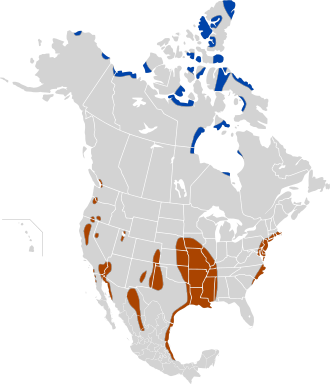

Unfortunately, by the time CUBs was launching around the time I worked at Cornell, House Sparrows were in trouble. Their numbers have been declining for decades in the U.K. and Europe.

When I went to Europe in 2014, I hardly saw any, though Eurasian Tree Sparrows were quite easy to find, and I saw very few in Uganda last month. American ornithologists aren’t quite prepared to say any decline in House Sparrows poses a problem, at least on this side of the Atlantic, but even here their numbers have dropped precipitously according to Breeding Bird Survey data.

These lowly little sparrows evolved with the earliest humans and have been part and parcel of our civilized world from the very start. Right now we are growing so polarized and fragmented that some of the very underpinnings of civilization, including the scientific method and the very nature of facts and truth, are unraveling before our eyes. It’s obviously a coincidence, yet unsettlingly ironic, that this companionable little bird, the species most associated with human civilization throughout our long history, would be disappearing right now. It’s almost as if they're abandoning ship.