Two or three decades ago, I came up with an imaginary product, Earth Angel Bird Identification Earrings. Shaped like little parabolas, they collected sounds, sent them via a discreet wire to a teeny tiny microchip sewn into the birder’s wide-brimmed hat, and whispered the correct identification back into the wearer’s ears.

Many years later, a real-life app named Shazam came out—it will identify just about any published recorded music, whether you’re hearing it in a restaurant or on the radio. Shazam’s database is enormous, but the algorithm does not recognize melodies, instruments, or singers’ voices. If you go to a live concert, even if the musicians are duplicating their own recording as closely as possible, Shazam won’t recognize it, much less a hummed or keyboard version of a melody. It identifies only those specific song recordings in its database.

Shazam’s limitations are exactly why bird song identification apps have been so hard to create. Every single song a bird gives is a live performance, and for only a few species is each performance of the song essentially identical to other performances.

To make an algorithm identifying bird songs in the field even trickier, birds do not take turns singing. In spring and early summer, especially at dawn, dozens of songs can be heard simultaneously. Shazam can deal with background noise, but not with two songs playing at once. Experienced birders can tease out the identifications in a dawn chorus, but no one has figured out how to program software to do that.

Despite the difficulties, over the past decade, several groups have developed primitive programs to identify bird songs and calls. One app has come sort of close—Song Sleuth.

One of the country’s top bird illustrators and field guide authors, David Sibley, provided all the artwork, detailed species information, and range maps for Song Sleuth. The company that developed the algorithms for analyzing the songs, Wildlife Acoustics, has a long track record of helping monitor bats, frogs, and whales via acoustics. The trick for Song Sleuth is that there are an order of magnitude more bird species than bat, frog, or whale species, and the vocalizations of many individual bird species are far more variable, too.

On Monday when David Sibley and Michael Collin, another leader in the Song Sleuth team, were in town for a convention, they took me out to test Song Sleuth at one of my favorite local birding spots, the Western Waterfront Trail.

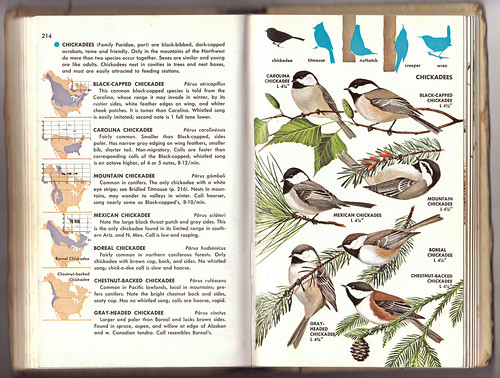

Before we started out, they helped me adjust a few of the settings of my app, and showed me how to use some features—Song Sleuth is one app that probably really does work best when you view the video tutorials first. It uses spectrographs, also called sonograms, extensively. I love that—I’ve used sonograms a lot, from the very start of my birding in 1975, thanks to the ones Chandler Robbins put in the Golden field guide.

|

| The Golden Guide included sonagrams by the range maps for most species. |

The process of using Song Sleuth is fun and easy. When you start the app, you click on the spectrograph icon, “Record and ID,” and Song Sleuth starts listening. Then, when you hear a sound you want to identify, you press the Record button. Sound Sleuth grabs sound starting from a few seconds before you pressed the button, giving you a fairly generous reaction time. When you press the button to stop the recording, the app gives you three choices of likely suspects, and an option to look at the spectrograph you produced. If the sound you want to identify is higher or lower than background noise or other bird songs, you can zoom in and move the spectrograph around so anything above and/or below your bird's sound won't be visible on your screen. You can also press a little scissors icon to cut out the sounds before and after the sound you want. Then when you press the arrow, it’ll base its guesses specifically on the sound you’ve selected.

How did our field test turn out?

First the bad news. It did not correctly identify most of the closest, loudest, clearest birds we heard. Its database includes only about 200 species altogether, many of them not found in Minnesota. A great many birders have found well over 300 species in the state, so there are obviously going to be a lot of bird sounds we hear that are not in Song Sleuth's database. Specifically, it does not have several of the species we most often identify by song on warbler walks at the Western Waterfront trail.

One of the first birds I got a perfect, clear recording of was a very nearby Swamp Sparrow. Unfortunately, none of the choices Song Sleuth provided was the right one. The Swamp Sparrow is a very common bird with a song people often want help with, because it’s so easy to hear but stays hidden in vegetation. Unfortunately, the Swamp Sparrow is one of many species not yet included in the Song Sleuth database. David wrote it down on their to-do list, so in future updates it should be added, but right now Song Sleuth would be worthless for working out that song, or the Marsh Wren, Brown Thrasher, Sora, or Virginia Rails that are often heard along the same trail.

Even though Song Sleuth's database does include the Song Sparrow, it misidentified just about every song produced by a nearby Song Sparrow, usually not even having the Song Sparrow as one of the three possibilities. This song is variable between populations, between individuals, and even within a single individual’s repertoire, which explains why David Sibley got the right result for one song but not for others sung by the same bird in the same spot. If the algorithm can’t work out this common species with a fairly straightforward song more consistently, I don’t see how it’s going to get other, more variable species consistently right.

Species that are in the database but are not listed as possibilities for Minnesota in summer even though they breed in our neck of the woods include Dark-eyed Junco, Pine Siskin, Golden-crowned Kinglet, Brown Creeper, Blue-headed Vireo, Connecticut Warbler, and Northern Waterthrush. Species in the database that aren’t listed as possibilities for Minnesota in summer even though they breed in the south include Tufted Titmouse and Eastern Screech-Owl For large states, it might be better eventually to be able to fine-tune the state filters by region.

Due to health reasons, I haven’t done a lot of birding this year, but of the 175 species, mostly common birds, that I have seen in St. Louis and Lake Counties since January, 75 are not included in Song Sleuth's database—that’s over 42 percent. Some of them are species we don’t normally hear vocalizing anyway, but some have distinctive calls or songs that can be important for detecting or identifying them: Trumpeter Swan, Ring-necked Pheasant, Ruffed Grouse, Common Loon, Pied-billed Grebe, Sora, Wilson’s Snipe, Common Nighthawk, Eastern Whip-poor-will, Alder and Yellow-bellied Flycatcher, Marsh and Sedge Wren, Swainson’s Thrush, Northern Mockingbird, Brown Thrasher, Rusty Blackbird, White-winged and Red Crossbill, and Evening Grosbeak. Song Sleuth has a long way to go to have the ability to identify bird songs with the accuracy that Cornell’s Merlin app achieves with photos.

One irritation for me that most users wouldn't be bothered by: Scrolling through the list of birds in Song Sleuth is not easy if you’re used to seeing birds in a logical order, either taxonomically or alphabetically. As far as I could tell, we’re not given an option to list them any way except the default, which is alphabetically by an inconsistent combination of arbitrary family and order names. The Osprey, belonging to the same order but a separate family from hawks and eagles, was put under the Os, far away from the H’s where "Hawks and Eagles" are listed, but the Barn Owl is in with the other owls even though it belongs to a different family. To find the warblers, don’t look under W for “Warblers” or “Wood-Warblers”—they’re under N, for “New World Warblers.” The Gray Catbird is listed under M for "Mockingbirds and Thrashers," even though the database includes no mockingbirds or thrashers. The blackbirds are listed under O for "Orioles and Blackbirds." The Olive Warbler, now separated from the wood-warbler family, is in its own category under O for “Olive Warbler,” but a common bird in California, the Wrentit, which is the only regularly occurring member of its family in North America, is mystifyingly listed under S for “Sylviid Babblers.”

Within each family, species are arranged alphabetically, but not by the common name, as the families are arranged. They've put the scientific names in alphabetical order, which completely baffled me. I wish there were an option to list them in taxonomic order, or even in alphabetical order by common name. I found their arrangement awkward and counterintuitive. Of course, most people won’t be scrolling through the entire bird list, and there is a search box so you can type in the name of a species you’re trying to look up, so this may be nothing more than a minor personal issue.

David Sibley added the Swamp Sparrow to his to-do list, and the number of species Song Sleuth can identify will grow, but right now it simply does not have a big enough database to help with a sizable proportion of the birds you’ll hear, and unless you already know bird song identification well enough to not need Song Sleuth, you won’t know whether the bird you’re hearing is in the database or not. It always gives three choices, and if you don’t know any better, you’re likely to assume your bird is one of them. It never even occurred to me until we looked for it that a common bird like Swamp Sparrow, much less Brown Thrasher or mockingbird, wouldn’t be in the database at all. And in both my test use on Monday and in pulling it out a few times since, I've had very inconsistent results with common species that are in the database.

The more people buy Song Sleuth, which costs $9.99, the more Wildlife Acoustics will be able to afford to invest in improving the program, but I’m still not convinced it’s even possible, with the current size of processors in smart phones or even laptop computers, to create an app that can actually identify all the bird sounds of any single place, just like Shazam will never be able to recognize a tune except as a published recording in its database.

I’ll enjoy watching Song Sleuth continue to make improvements, and I'll love if they prove me wrong about whether it's truly possible to "turn your iPhone or iPad into an automatic bird song identifier," but for now, Song Sleuth is not an app I’ll be using.

If you want to learn bird songs, you'll be better off using Cornell's Merlin app, the Sibley eGuide to Birds app, Cornell's All About Birds website, their All About Birds bird song tutorial, or any of dozens of other ways of accessing bird songs. At least for now.