I’m writing this in my daughter’s apartment in the Gowanus neighborhood of Brooklyn. I’ve been spending a week in New York City with Katie and my future son-in-law and their dog Muxy. They’re in a new apartment, and the very first species I saw in their yard was a Northern Cardinal. So far I only have four species here, with Rock Pigeon, European Starling, and House Sparrow making up the balance.

Last year when I came in December, I spent time at the Brooklyn Bridge with Heather Wolf, who wrote Birding at the Bridge: In Search of Every Bird on the Brooklyn Waterfront. This year I was on my own, and most days had something going on with family. But Tuesday I decided to visit the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge. So first thing in the morning, I walked with Katie to the subway. She got on the A train headed for Manhattan where she works; I went down a level and hopped on the A train headed in the opposite direction, toward Far Rockaway in Queens.

It was a nice long ride, much above ground, and I regretted having my binoculars in my backpack for the nice long stretch near JFK Airport, where we passed lots of waterfowl, including Mute Swans and Brants. When I got out at the stop marked “Broad Channel,” I pulled my binocs out of my backpack and took a short stroll through a neighborhood that brought me to the Cross Bay Boulevard, about ¾ mile from refuge headquarters. There’s a nice walking and biking path along there past waterfront houses, with a couple of access points for looking at birds in the water. I was already regretting bringing my more portable 8x32 binoculars instead of my heavier, bulkier 10x42s, and through the day wished I’d had more power for the distant birds.

At the first access point, right when I got on the Boulevard, I walked close to the water and set my backpack down. First I turned on the eBird app on my cell phone. It has a cool new GPS feature that not only keeps track of the time you begin and end, but also exactly where you walk, so all I had to do was mark in the birds I saw and now I have a permanent record of the trip.

Then I pulled out my camera and lens. I had to move slowly, because just a few feet away were a pair of Mute Swans—I wanted some nice face close-ups, so had to be careful not to scare them. There was enough vegetation between us to make it hard to take the perfect photograph, but I didn’t mind. I prefer my photos to show birds as they really are, not as I wish they would pose for me. I saw plenty of Mute Swans from the train, but these were the only ones I saw on the walk.

That first spot was also where I took my best photos of Brant. These saltwater geese are abundant, but not the least bit sociable as far as humans are concerned, so I don’t have any good close-up photos. The photos I took were not just my best Brant photos of the day—they’re the best I’ve ever taken.

The other access spots along the walk weren’t quite as good, but the walk was fun. The Callahead Porta-Potty company’s headquarters are right there, so I saw lots of pumping trucks with such messages as “Number One in Dealing with Number Two.” Road traffic was moderate, but I didn’t pass any pedestrians and only one bicyclist before I got to the refuge headquarters.

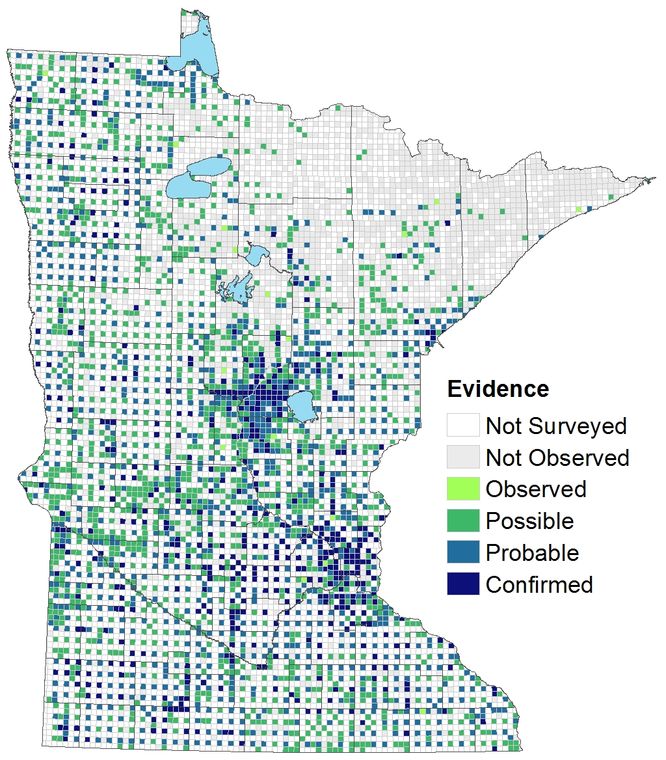

I didn’t have the refuge entirely to myself—as I walked the 1.7 mile loop around the East Pond, I passed three couples. One woman wore binoculars, and we had the kind of quick, friendly exchange birders always do when they’re having fun but aren’t seeing many birds. Most of the water birds were too far away for great photos, and there weren’t all that many songbirds—I came upon one flock of robins, and two collections of skittish, photo-shy Yellow-rumped Warblers with some sparrows, but didn’t see a single chickadee. There were a few thick conifers near the path that I checked thoroughly just in case a Saw-whet Owl might be hidden within.

I saw 30 species on the walk—fewer than I’d hoped for, but I took a lot of joy in seeing each one. Finding moments of real solitude in view of Manhattan seems improbable.

With the current push toward privatizing parks and refuges, this kind of urban wildness adventure may soon be a luxury of the past, but I relished every moment. New York New York IS a wonderful town.

|

| The Bronx is up and the Battery's down. |

Here are my eBird lists. This first one is from where I started walking along the Cross Bay Boulevard up to reaching the refuge headquarters.

Broad Channel, south of JBWR HQ, Queens, New York, US

Dec 19, 2017 11:05 AM - 11:33 AM

Protocol: Traveling

0.688 mile(s)

20 species (+3 other taxa)

Snow Goose (Anser caerulescens) 2

Brant (Branta bernicla) 300

Canada Goose (Branta canadensis) 27

Mute Swan (Cygnus olor) 2

Gadwall (Mareca strepera) 10

Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) 12

American Black Duck (Anas rubripes) 10

Greater/Lesser Scaup (Aythya marila/affinis) 2

Bufflehead (Bucephala albeola) 4

Ruddy Duck (Oxyura jamaicensis) 4

Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) 1

Ring-billed Gull (Larus delawarensis) 2

Herring Gull (Larus argentatus) 8

Great Black-backed Gull (Larus marinus) 1

gull sp. (Larinae sp.) 10

Rock Pigeon (Feral Pigeon) (Columba livia (Feral Pigeon)) 50

Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura) 2

crow sp. (Corvus sp. (crow sp.)) 1

Ruby-crowned Kinglet (Regulus calendula) 1

European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) 55

Song Sparrow (Melospiza melodia) 2

House Finch (Haemorhous mexicanus) 1

House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) 15

The second checklist is from my walk around the East Pond at the refuge.

Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, Queens, New York, US

Dec 19, 2017 11:41 AM - 12:52 PM

Protocol: Traveling

1.713 mile(s)

23 species (+1 other taxa)

Snow Goose (Anser caerulescens) 10

Brant (Branta bernicla) 2000

Canada Goose (Branta canadensis) 200

Wood Duck (Aix sponsa) 1

Northern Shoveler (Spatula clypeata) 8

Gadwall (Mareca strepera) 2

Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) 30

American Black Duck (Anas rubripes) 18

Bufflehead (Bucephala albeola) 4

Ruddy Duck (Oxyura jamaicensis) 6

cormorant sp. (Phalacrocoracidae sp.) 10

Ring-billed Gull (Larus delawarensis) 1

Herring Gull (Larus argentatus) 30

Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura) 22

Belted Kingfisher (Megaceryle alcyon) 1

Downy Woodpecker (Picoides pubescens) 1

Northern Flicker (Yellow-shafted) (Colaptes auratus auratus/luteus) 2

American Robin (Turdus migratorius) 11

European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) 45

Yellow-rumped Warbler (Setophaga coronata) 20

American Tree Sparrow (Spizelloides arborea) 1

Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis) 1

White-throated Sparrow (Zonotrichia albicollis) 2

Song Sparrow (Melospiza melodia) 5