Tuesday, February 27, 2018

Olympic Gold and Duluth's Curling Club!

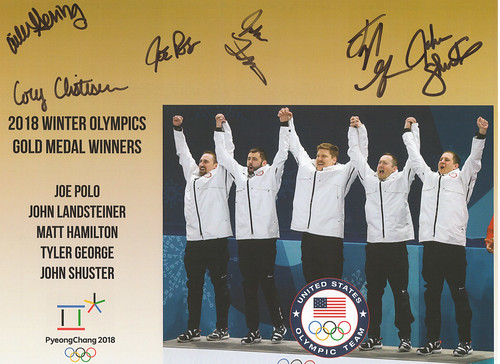

Today the City of Duluth, the City of Superior, the Duluth Entertainment and Convention Center, and the Duluth Curling Club honored the Olympic champions, so Russ and I went to the DECC to see them. It was wonderful fun.

Monday, February 26, 2018

Of Lifer Owls and Extraordinary Sporting Wins

I was still recovering from my heart attack, which had happened just five weeks before, so I wasn’t very active birding that first spring with her, but the day after we got home from Chicago, crows yelling their heads off alerted us to a Great Horned Owl just three doors down. That was the first owl on Pip’s lifelist, and being so close to our yard, it reinforced my commitment to stay with Pip any time she went out after dark. (Now as an adult weighing 9 pounds, Pip weighs almost twice what the heaviest Great Horned Owl on record weighs, and more than twice what one of their favorite prey, snowshoe hares, weigh, but when she was a three-pound puppy, she’d have been easy pickin’s. Even at full weight, she’s small enough that she could be killed easily by a Great Horned Owl, but too heavy for it to carry her off. An owl would have had to eat her on site.)

The week after I brought Pip home, we saw the other large owl that could make an easy meal of her—a Snowy Owl in Superior. It was more than a month before Pip saw another wild owl—an Eastern Screech-Owl in Ohio during the birding festival called the Biggest Week in American Birding. She was already familiar with screech owls because of my little Archimedes, but the Ohio bird was her first in the wild.

|

| I saw this Eastern Screech-Owl at the Magee Marsh the year before Pip was born. But it COULD be the one she saw, too. |

Pip added lots of birders as well as birds to her lifelist in Ohio.

|

| J. Drew Lanham and Pip are good friends! And Pip got to hear his voice this December on the radio when Drew and I were guests on Science Friday! |

Pip and I didn’t see another owl until that September, when a saw-whet was calling and hunting in my backyard one evening. And then we went more than a year before Pip added another owl to her lifelist. That was about one in the morning on November 3, 2016, the night my beloved Chicago Cubs won the World Series. The game was over at 11:47 pm, very late for me, but I was so elated that I couldn’t pull myself away from the TV for over an hour. When I took Pip outside, a Boreal Owl was calling away, and moving from one neighbor’s yard to another to my yard, apparently actively hunting. My education owl Archimedes was trilling in response. Nature itself approved of the Cubs finally winning, and Pip was still wearing her little Cubs jersey as she added this splendid lifer.

That was it for owls on Pip’s lifelist until just this week. On Monday, February 19, exactly the day the Duluth Curling Club, a.k.a. Team U.S.A., started winning games in the lead-up to Olympic Gold, Pip started seeing owls again. That is when we went birding with my friend Susan Szeszol.

... and the great gray flew too quickly...

... but nevertheless they were lifers for both Susan and Pip. Tragically, I forgot all about my practice of serving brownies after seeing owl lifers.

Then on Friday, I heard crows cawing somewhere nearby and took Pip to check it out. We found another Great Gray Owl, this one barely photographable, roosting in the aspens across from St. Michael’s Church. Those noisy crows, intrepid little chickadees, a couple of Downy Woodpeckers, and a Red-bellied Woodpecker bombarded it as it sat tight. I didn't get any photos showing the actual bombardments, but if you look carefully above and to the left of the owl, you can see a Downy Woodpecker raining expletives on the poor bird.

Then on Saturday, Pip and I went to the bog again. This time we got even better looks at a Great Gray Owl, on the power line on our side of Highway 7; after several minutes, it dropped to a lower perch for a while. Pip was fascinated—I think this was her best look at any owl ever except for Archimedes. I was so darned intent on photographing the owl that I didn't even think to take a photo of Pip watching it.

Apparently thanks to the Duluth Curling Club having just won the Olympic Gold Medal at 2 am that very morning, Pip and I also saw a Boreal Owl—a Boreal Owl seems to appear for Pip right after extraordinary achievements of our favorite teams. As with the owl after the Cubbies' win, I couldn't take a photo—too many people had hiked too close to the owl already. This time Pip wasn’t wearing a Duluth Curling Club jersey, but apparently whatever deity arranges these wonderful coincidences knew what was in our hearts. Susan had returned to Chicago with the northern owl trifecta. Pip had two lifers and now yet another acknowledgement that Nature itself approves of our beloved teams. That was a win for all of us.

Tuesday, February 20, 2018

Get a grip!

Birdwatching is like a box of chocolates: you never know what you’re going to get, but it’s certain to be sweet. That’s what I always say, and that was exactly what happened this weekend at the Saz-Zim Bog Winter Birding Festival. I’d brought my little birding dog Pip along because she needed a few lifers that have been appearing now and then, in particular the Great Gray and Northern Hawk Owls. We missed out on them in the bog, but did get one really cool and unexpected treat.

I spent Friday and Saturday nights with my good friends Gail and Chuck Prudhomme in Meadowlands, and headed out Saturday morning with Pip to go birding on our own. But before we even made it to the car, I spotted a Ruffed Grouse in a birch tree. The sun was shining as I aimed my camera toward it and started clicking away. I ended up with a series of detailed photos at close range, showing the grouse eating buds, its feet gripping branches and even small twigs—easily my best Ruffed Grouse photos ever.

Up until Saturday, I’d seen grouse feet at close range only in museum drawers, but those feet are so fascinating in life that I was thrilled to have a close-up view of them in actual use.

Every year in mid-September, long, stiff projections start growing from the scales on the sides of grouse toes. It takes about three weeks for these growths, called pectinations, to reach full size. Those growths fall off in the spring—usually in late April or early May, but sometimes as early as late March.

The stiff pectinations greatly expand the surface area of the grouse’s feet, so are usually explained as “snowshoes,” because they presumably help Ruffed Grouse walk on the surface of deep snow without sinking. Gordon Gullion had another explanation which makes sense, too—he believed that the pectinations help the grouse grip icy branches while feeding on buds.

The two explanations both seem not just plausible but equally important for grouse survival in their range, where winter weather includes both ice storms and deep snows, in the same way that my good winter boots have grippy soles for walking on ice and are high enough for walking in deep snows. It’s nice to have foot coverings that do the job no matter what the weather throws at you.

Like most birds up here, grouse plumage is thicker in winter than in summer—they lose feathers in spring before they start replacing them. The ones up here are well feathered on their tarsi—what we intuitively but not quite accurately call their legs. My photos show that thick feathering, too. They can also take refuge from cold and wind under a literal blanket of snow when that is available.

One of the Ruffed Grouse’s most important winter adaptations isn’t visible on the outside—two blind offshoots where the large and small intestines meet, where our appendix is, called caeca (or ceca), grow enormous in winter. Within the caeca, digestion of aspen and birch buds takes place thanks to anaerobic bacteria that produce an enzyme to break down cellulose in the woody tissue. In spring, when the diet changes to more digestible leaves, fruits, berries, and insects, the caeca shrink.

So surviving winter is, for Ruffed Grouse, a literal as well as figurative matter of intestinal fortitude. It’s hard to say whether their special foot adaptations help them maintain their emotional equilibrium in winter, so I don’t know how well those pectinations help them, in the figurative sense, to get a grip. But sometimes a literal grip is all anyone really needs.

Friday, February 16, 2018

Sax-Zim Birding Festival and the Great Backyard Bird Count

This weekend is a big one for me—it’s the Sax-Zim Birding Festival centered in Meadowlands, and I get to be the keynote speaker: I'll be talking about how birds survive winter.

This also means I get to spend the weekend with my good friends Chuck and Gail Prudhomme, who live on the Little Whiteface River. When I was doing regular Big Days, my team used to stay in a lovely cabin on Chuck and Gail’s property. We always started with me getting up, at 2:30 am. I’d head to the outhouse first to try to call in a Barred Owl. Most people are too impatient with owls. I’d call two or three times, then head back in the cabin to get dressed. By the time our team of four was ready to set out, at least one and often a pair of Barred Owls had silently flown in. At that point, we'd call back and forth a bit. Only once did I get a response from the direction of Chuck and Gail’s house, in a voice that sounded suspiciously like Chuck’s. But even that year, the real owls flew in before we left. And even in the dark at 2:45 am we usually heard at least a couple more species before we headed out.

I also rented Chuck and Gail’s cabin once when my daughter was home from college—she and I had a wonderful mother-daughter bonding experience there, just the two of us on a beautiful August evening. I’ve only spent a bit of time at Chuck and Gail's in winter, but I’m looking forward to making sound recordings at their bird feeders this time. And the best thing, of course, will be getting to spend time with them again.

Registration for the festival has been filled for quite a while—Meadowlands is tiny, and so they set maximum registration at 150. The big draw, of course, is winter owls, and this year promises to be good. I always have mixed feelings about that—the Great Grays and Northern Hawk Owls come for the meadow voles in the open boggy habitat; the boreals for our lovely woods where they try to sit with their eyes mostly closed in hopes of being unobserved, or when they’re in desperate straits where they try to hunt without distractions.

But the moment people spot them, all bets are off. For some reason, our species—the one species on the planet that includes rocket scientists and Red Cross nurses—isn’t very smart or kind about wildlife, perhaps especially owls. I’ve talked to several people this winter who saw people walk straight toward owls, which invariably got the owl distressed enough to fly off. I’ve heard even supposedly knowledgeable birders claim that this isn’t harmful—birds fly when they’re stalked by natural predators, too—but there are a heck of a lot more of us than natural predators. Every time we disturb an owl, we make it easier for it to be spotted and harassed by crows or jays, or even chickadees. Chickadees can’t hurt even a tiny saw-whet or boreal owl, but their tiny obscenities do alert larger birds that can harm the owl. Many bird guides do their darnedest to keep their groups at a respectful distance—that’s what spotting scopes are for. Sometimes, of course, even the most respectful birders get very close to an owl, but that depends on the owl flying in, not the birder walking ever closer and closer.

My very best photos of a Boreal Owl ever were taken in Two Harbors. Russ and I had been looking for one, and then Jim Lind spotted us and came down to visit. We were chatting away for several minutes before we looked up and there it was! We watched it as it even caught a shrew. And the sun was behind us, so all my photos show it in perfect or at least pretty good light.

Of course, most of my Boreal Owl photos are of birds with their eyes mostly closed—the way they try to keep their eyes while roosting, because those round yellow eyes are a clear signal of danger to other birds, which will try to drive away the little guy. I see way too many photos of owls looking alarmed, clearly by the photographer.

For me, the first rule of birding is “Above all, do no harm.” With luck, respect and generosity to the birds will prevail at this weekend’s festival.

This late-winter count gets numbers quite different from the early-winter Christmas Bird Count, and uses an entirely different protocol—for the GBBC, you count every bird you see, keeping track of where you saw it. You don’t need to be part of any official group, staying within a specific count circle. The data helps us keep track of bird movements in different winters, which is important for tracking population trends.

All you have to do is go to eBird.org or birdcount.org to participate. If you’re reading this after the weekend is over, you can still submit the birds you saw this weekend at eBird.org. When you register, which is free, you can opt out of receiving emails from Cornell or Audubon. I support both organizations because they provide so much valuable information for the general public as well as for scientists and conservationists, but you don’t have to give them money or read their emails to get to use their valuable services.

The cool thing about eBird is that it will keep track of your birds for you, so once you’ve submitted data, you can then use it to effortlessly keep track of your lifelist, year list, backyard list, and county lists. And on top of that, the data helps scientists protect those very birds. If you’re not using eBird, this weekend is a great time to start. If you’re going out to see birds, great! If you’re stuck indoors, you can report just what you see looking out the window. It’s fun, it’s valuable for both scientists and the birds they study, and it’s the right thing to do.

Tuesday, February 6, 2018

Superb Owl Sunday, and Mass vs. Volume

The first Sunday of February tends to coincide with important annual rituals for many Americans. I spent the day, which I call Superb Owl Sunday, birding with my friend Lisa trying to find a superb owl, or even a standard one. Many more Americans call that day of the year Super Bowl Sunday and watch a football game rather than spending the day in nature looking for owls. Based on what we saw, we could have predicted the football game’s outcome: we encountered several Bald Eagles but not a single person who we could be sure was a patriot.

Unfortunately, we did not spot any owls. I’m afraid an owl tragedy earlier in the week may have caused our bad luck. My friend Erik Bruhnke, who has been staying with us this winter, came upon a dead Great Gray Owl on a roadside a bit northeast of Duluth. The poor bird’s body was in excellent condition except for being dead—it was presumably killed in a car collision. Erik salvaged it for an educational institution, but had to keep it at our house until he worked out a time to drop it off.

We took a few photos of it—there are some extraordinary features of owls that living birds hate to show off. I could tell that my little education owl Archimedes did not like me to show his ears to people, so I don’t approve of bird banders or other people pulling the facial disk forward to show the ears of a banded or education bird—I think the gush of air into the ear must hurt. When I want to show what owl ears look like, I use photos I took back after the infamous Halloween snowstorm of 1991. There was no way migratory owls could get food under that heavy, deep cover, and so people were finding dead owls, especially Long-eared Owls, as they shoveled out. So I photographed the ears, behind the facial disks, of an owl on its way to the Bell Museum.

I am dismayed to report that I didn’t even think to photograph this poor dead Great Gray Owl’s ears—that would have been truly fascinating, because their ears are humongous.

I did photograph the primary wing feathers, and got pretty good close-ups of the leading edge of the outermost one. That feather is responsible for the absolute silence of the owl’s flight—the rather stiff edge looks like a comb, the tiny teeth breaking up each wing’s whoosh into more than a hundred tiny whooshes.

I don’t think any bad Karma could be associated with those photos. The bad Karma that kept me from seeing a single owl on Superb Owl Sunday was because of another photo I got. The owl was huge—roughly 2 ½ feet long with a five-foot wingspan. That prompted me to weigh it—it weighed merely 3 pounds, which is on the heavy, well-fed side for a Great Gray. These birds are just feathers and spirit, and not a whole lot else.

I couldn’t help but compare that huge yet featherweight body with my dog Pip. She’s a tiny, fluffy dog, easy for me to pick up and carry with one hand; Pip weighs about 9 pounds. That gave me the idea to set her on the floor next to the owl for a size comparison. She did not like the idea, though she cooperated and was respectful of the poor owl, who was beyond caring. Sure enough, Pip is noticeably smaller than the owl, yet she weighs three times as much!

This all set me to wondering why the word “massive” is usually used to describe things of large volume, not mass. I’ve often read that the Great Gray Owl is massive, while no one larger than the tiniest mouse would ever describe Pip as massive—even our backyard squirrels laugh at her. Yet she’s fully three times more massive, in literal mass, than the largest owl in North America. Now I have a photo demonstrating the difference between mass and density, but it came at the cost of being punished on Superb Owl Sunday. With the Minnesota Vikings, all I can say is, “Maybe next year.”

Friday, February 2, 2018

Stop Bird Collisions with Zen Wind Curtains

The Vikings’ US Bank Stadium was built with bird-killing glass despite how many of us tried to persuade them to build it of a safer, more energy-efficient material, such as the glass in the new Dallas Cowboys’ stadium. A lot of our own houses are also built with bird-killing glass windows, but it would be prohibitively expensive to put in all new windows. This week I talked with Jeff Acopian, a Pennsylvania engineer who invented a reasonably inexpensive yet very effective solution for protecting birds from window collisions, researched and endorsed by the one scientist who has been focusing on window kills his entire career, Dr. Daniel Klem. Jeff told me more about his Acopian BirdSavers, which he nicknamed Zen Curtains.

|

| Jeff Acopian |

J: Hi, Laura! We actually call them Zen Wind Curtains, because when they blow in the wind, it has kind of a calming effect on people.

L: That's even cooler! Did you have any personal experiences with bird collisions that made you motivated to do something about the problem?

J: Yes. Back in the early 1980s, we had birds that were hitting our house—our home in Pennsylvania. And it was really very distressing to us. It seemed like a lot of the birds we saw dead were interesting species as well, which was even more distressing. The rarest bird we ever saw was a Yellow-billed Cuckoo. I never even knew they existed here. This was when I was in my teens. We saw this dead bird--it looked so strange because we'd never seen one alive.

J: And we've also had thrushes, juncos, and cardinals...just typical—any bird that flies around. We figured we wanted to fix this problem. I don't know if you remember back in those days, they had these beaded curtains that people would hang in their doorways?

L: Oh, yes--Rhoda had those on the Mary Tyler Moore Show.

J: Right. So what we did was take those beaded curtains apart and we hung each of those strips of beads about 4 inches apart on the windows outside, and that worked! It stopped birds from hitting the windows.

J: So those beads lasted for many years, and finally they started to deteriorate, and we couldn't find those beads anymore so we hung thin bamboo poles. And that worked as well, but it looked horrible. And finally I got the idea to hang para-cord, which is parachute cord. And that works very good, and looks very good, and it's easy to do.

L: I'm curious how you even thought of parachute cord. Do you have experience with parachutes?

J: Well, actually, yes. Back in the '60s my dad used to parachute. He was one of the first people to do sport parachute jumping. All I know is I wanted to put something there that would replicate the beads and replicate the bamboo poles, and it seemed like parachute cord would be good if it worked, because it's supple, it lasts long, and it looks good.

J: People who haven't actually seen BirdSavers, they see the words cords on the window and they think, "Oh, boy! That's gonna look horrible!" But then when they actually see BirdSavers on a window, their opinion changes, because they look so good and they don't really obstruct the view. And people can do it themselves if they want to. We actually give DIY instructions on the BirdSavers website on how to do that, but I know a lot of people won't want to make them, so we will make them for people. But, really, the idea is just to get the message out there that this can be done easily.

L: Describe what's involved—how close together are they, how long are they, how do you suspend them from the window?

J: We put them about 4 inches apart. Four inches is a good number. The ones that we make stop about an inch and a half or so above the glass, so it looks nice—you can see the bottom of the cords. And there's various ways to attach them at the top, and various ways to attach each individual cord.

J: I actually know someone who wrote me an email from Sweden. They made BirdSavers but they put curtain fixtures on the outside of the window, so at certain times they would roll them back just like a curtain. So they did that with BirdSavers.

L: I have a link to BirdSavers on my blog along with windows with Zen Wind Curtains. I asked Jeff what he most wanted us to remember.

J: There's a lot of people who don't care if they kill birds at their windows. That I know. But I also know there's a lot of people who do care. I really want people to know about BirdSavers. It's such a simple, elegant, aesthetically pleasing, inexpensive solution to a major problem. I just don't know of any other solution like that.