Today is the 50th anniversary of Russ’s and my first date. Our courtship was rather Canada Goose-like, in that we were still dependent young in high school when we started dating. Every fall, Canada Goose families join other families in large flocks of related and unrelated birds, and rather like high school, the young start noticing one another and little by little pair off, sometimes hanging out for a bit before breaking that relationship off and starting a new one. When they do finally make a permanent selection, they stick together through thick and thin, year-round. Goose marriages virtually always last as long as both birds survive, though considering that the oldest Canada Goose known to science lived only 33 years and 3 months, the chance of two birds selecting each other when young and each one living over half a century to make it to their golden anniversary is pretty remote.

The one wild bird known to be even older than me, Wisdom the Laysan Albatross, has had at least two different mates just since 2011 or so, when a curious Chandler Robbins started going back through the non-computerized banding data, painstakingly tracing back the band numbers to her original banding in 1956. Her mate wasn’t banded in 1956, nor at any other point until she got so much international attention as the world’s oldest known wild bird, so we can’t know whether any of her relationships have lasted as long as Russ’s and mine.

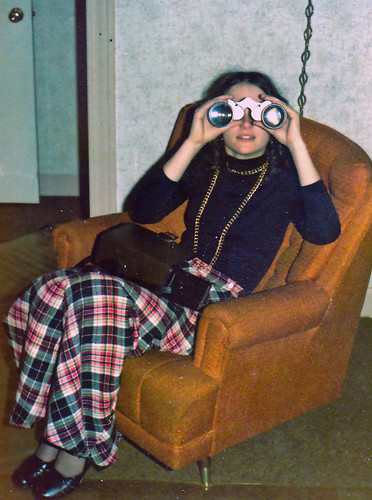

I wasn’t a birder in 1968 when Russ and I first went out. I didn’t become one until almost three years after we got married—Russ told his mom to give me binoculars and a field guide for Christmas in 1974. We went up to Port Wing, Wisconsin, for a few days before classes started in 1975—my first time ever birding up here—and I added lots of lifers and spent lots of time studying fall warblers for the first time. So I always associate the end of August and Labor Day weekend with big warbler migrations. And yesterday was one of those days. I was busy and had to spend most of the day indoors, but when I did get out for a few minutes with my new camera lens, I had a field day. The warblers were so thick, and so close, that I actually had to step back several times to be able to focus and to get a whole bird in the frame.

The most abundant species was the American Redstart.

The most cooperative for photos was the Chestnut-sided Warbler.

One Magnolia Warbler spent an inordinate amount of time in my neighbor’s tamarack tree, peeking out for several photos.

And a Cape May Warbler in my own front yard spruce tree gave me lots of photos from my porch—that one was probably a young female, very beautiful in a subtle, quiet way, missing all the gaudy field marks that so distinguish spring males.

Today, to celebrate our anniversary, Russ and I will be driving up the shore for a few hikes. I’ll be more focused on him than on migration, but I’ll certainly have my binoculars and probably my camera, just in case. I don’t know if the warblers will be as thick as yesterday—migration is like a box of chocolates: you never know what you’re going to get, but it’s certain to be sweet, just like two high school kids sharing their very first good-night kiss.