When I started birding in 1975, my only optical equipment was a pair of Bushnell 7x50 binoculars. The next year, I got a Bushnell Spacemaster spotting scope. Russ and I were college students and there was no way we could afford film and developing, much less a long lens, for me to photograph birds. I was entirely satisfied watching birds without capturing them on film.

|

| Here is a Kirtland's Warbler I photographed in 2011. By this time I was more likely to be carrying a camera than binoculars! |

I got my first digital camera in 2000. It had two or three megapixels and a bit of a zoom. I took a few photos of close birds in Costa Rica and when visiting my aunt in Florida, but used the camera mainly for people and scenery, and more often than not, left it home when I was birding.

|

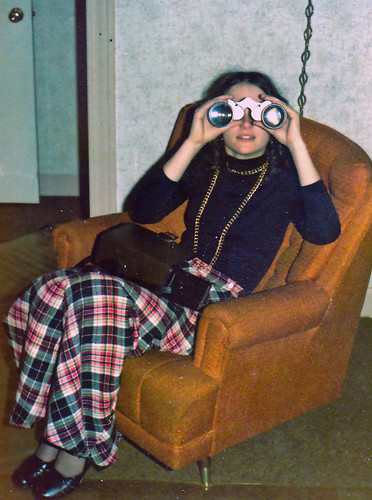

| I took this photo in Costa Rica in 2001. Very few photos of birds, but quite a few of my daughter Katie! |

|

| I digiscoped this Le Conte's Sparrow in June 2005, using a Canon PowerShot SD 500 and my Zeiss spotting scope. It's still one of my favorite photos ever. |

|

| Birders looking at this Ivory Gull in Duluth in 2016 spent more time photographing it than looking at it with binoculars. |

I’ve adapted with the times. In January 2009, when I was working at the Cornell Lab, I bought a good DSLR camera and a 100-400 mm lens. Now if I have to leave some of my optical equipment at home, it’s more often my binoculars than my camera, which I take everywhere.

I consider myself a birdwatcher who takes pictures rather than a nature photographer. It’s not that I don’t take myself seriously enough because I’m a woman, though I do think most people, male and female alike, take ourselves way too seriously. In this case, though, it’s that I invest my time and effort into learning more about birds rather than the principles of photography. Many of my photos have been published in magazines, and National Geographic even included one in my Pocket Guide to the Birds of North America.

|

| I photographed this Yellow-rumped Warbler with a small Canon point-and-shoot camera in 2006. This is the photo National Geographic used in my Pocket Guide to the Birds of North America. |

Ironically, sometimes people ask me to teach photography workshops, though I honestly have only one piece of advice for people who want to take bird photos: No matter how cheap or expensive your equipment may be, get out there and take as many bird photos as you can. Little by little, you’ll improve, and from the very start will get a few splendid photos.

I pretty quickly figured out that when a bird is backlit, it’s important to overexpose it.

It took way longer for me to figure out that when a bird is lurking in dark shadows, it’s important to underexpose it.

After years of using Photoshop and Lightroom, I’ve also grown better at tweaking my photos without over-tweaking them. But I’ve never learned photography systematically, so wouldn’t have a clue how to teach it the way I do it, by trial and error and just taking a whole lot of photos so I’ll have a little wheat here and there in the chaff.

Over the years, I’m finding that my percentage of good photos is improving, but I have the right kind of personality for my lackadaisical approach, in that I don’t get frustrated or upset when my photos turn out awful. People who put in the time and effort to learn how to take consistently good photos are the “real” photographers. I’m still just a birder who takes pictures. Real photographers get frustrated when their pictures don’t turn out, and when they take what looks like a genuinely perfect shot, they pay closest attention to what they could have done even better. Me—when I take even a marginally good shot, I’m overwhelmed with delight.

I’ll never be able to make a living as a photographer, but I probably derive at least as much fun and joy from my photos as most professional photographers do. My approach to bird photography is clearly not better on any objective scale, but it’s exactly the right way for me.