|

| Can I ask you a question, Mommy? |

When the internet started making it easier to track down information without running to the library, I started spending more and more time on the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s information-rich website. I doubt if a week goes by now that I don’t consult their

Birds of North America Online site at least once or twice.

I’d paid well over a thousand dollars for that amazing series when it was originally published in a paper version in the 1990s—each one of the more than 600 magazine-sized entries covers one species, and I have them all filed away in taxonomic order in my file cabinets. The

Online series provides a lot more information. Except in the world of Harry Potter, we can’t consult paper copies of anything to see videos or hear recordings, and as new information is added, paper copies can’t be magically updated. As a member of the American Ornithological Society, which published the original Birds of North America series, I get to use the online BNA for free, but if I couldn’t, it’s something I’d definitely pay for—anyone who depends on accurate information about birds and uses primary sources can’t do without it. The

BNA Online normally costs $42 for a year’s subscription, but you can get a single-month subscription for $5, and subscribing for two or three years at a time gives you significant savings.

If you don’t need that level of information, Cornell’s

All About Birds provides a lot of info plus sound and video, and it’s absolutely free. When I worked at the Lab, I helped write some of the All About Birds species accounts, and also answered many email and phone questions, as well as fielding such media inquiries as when a

New York Times reporter needed to know how likely is it that a person could get pooped on by a goose.

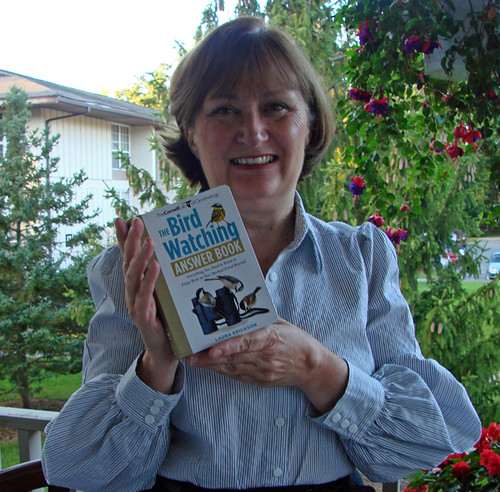

Another of my major assignments at Cornell was to write

The Bird Watching Answer Book, which has been, by far, the best-selling of

all twelve or so books I have written. That book compiled my answers to hundreds of questions I’ve fielded over the years.

After I left Cornell, I helped them by serving as a moderator for the chat room they set up for their Great Blue Heron nest cam—again, my job was primarily to answer questions.

So the truth is, I love to answer questions. One of the dear friends I made back during those heron nest cam days, Meg, asked me a question about geese last week.

Hi, Laura - silly question, but I want to be sure I'm correct before I respond to a statement: a female goose loses her flight feathers while she is on the nest so she can better protect the nest. I've never heard anything so silly but want an expert to say so.

First off, there is no such thing as a silly question. Over the years, people in all sincerity have asked me such questions as:

- Wouldn't it be healthier to use Nutrasweet or other artificial sweeteners than sugar in hummingbird nectar? (Answer: absolutely not!)

- Do hummingbirds really hitchhike on the backs of migrating geese? (Again, absolutely not!)

- Should I set out dryer lint for nesting birds? (Absolutely not!)

- Should I use food coloring in hummingbird sugar water (Again, absolutely not—and please don’t buy commercial hummingbird food that is red—it’s very unhealthy for them).

If I don’t consider those straightforward questions silly or stupid, I certainly don’t consider a question about the timing of molt to be silly.

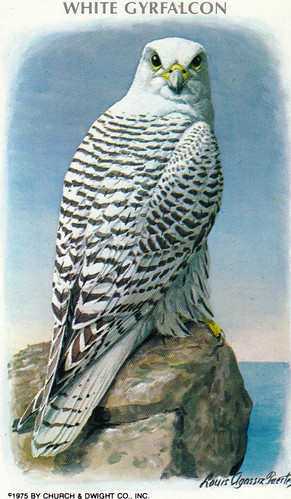

Most birds can afford to lose a few flight feathers at a time during molt without compromising their ability to fly.

|

If you can ignore the fact that this Turkey Vulture is pooping, you can see where

a missing primaryis being replaced by a new one. Most birds can fly, and even soar,

while missing a few feathers. |

Hawks, eagles, vultures, owls, songbirds, hummingbirds, woodpeckers, kingfishers, and a great many other species simply could not get food and water, elude predators, or do much else, if they ever underwent a flightless period after they leave the nest as fledglings. These birds have a large enough wingspan to support their body weight even without several flight feathers.

But water birds need a heavier, more robust body to be able to submerge long enough to get food under the surface. Geese feed a lot on land and virtually never dive underwater, but their heavy body weight is important because they do a lot of grazing; getting nourishment from grass requires a long, heavy digestive system.

|

Canada Geese never stop flapping except when coming in for a landing, and

need all theirflight feathers to support their heavy bodies. |

To be able to dive underwater to chase fish, loons can’t be buoyant or they’ll pop up like corks before they get close to the fish they pursue.

|

Loon wings are narrow with a relatively small surface area, just big enough to support

their heavy bodies.Their wings can be too small to support their weight if they're missing

any flight feathers. |

So in both cases, though for slightly different reasons, these water birds have small wings relative to their body weight, and would both have trouble staying aloft if missing one or two flight feathers; if three were missing during a molt, they might not be able to fly at all.

Loons and geese solve the problem by molting all their flight feathers pretty much simultaneously; if they can’t fly at all during wing feather molt, they might as well minimize their flightless period by getting the molt over with as fast as possible. The trick is timing this molt for when they don’t need to fly.

Loons molt during winter, while they’re out in the great big ocean or Gulf of Mexico. They can dive to elude aerial predators, swim underwater fast to elude swimming predators. When food in one area is scarce, they can swim to new fishing areas.

Geese, on the other hand, have an urgent need to fly during spring and fall, to migrate, but also during the dead of winter, when they feed on fields as well as in water during hunting season.

Meg was right to question whether geese could go through the nesting period without flight—at that point, a predator discovering the nest would force the goose to find a whole new place to start anew, so flying would still be important. It’s after the eggs hatch that geese start molting. They don’t dare fly away from their dependent young, and at this point they won’t be re-nesting if they do face a disaster.

Geese choose a nest site that is close to feeding areas, both on land and in the water, and for a few weeks, the entire family gets about by walking or swimming. The goslings will be ready to take wing as their parents finish up their own molt. The family will stay together through fall migration and winter.

One of the things I love about birds is how each species has its own strategies for survival. Some seem simple and straightforward. But even very simple processes, like keeping plumage fresh by molting feathers, can have some surprising complexities.