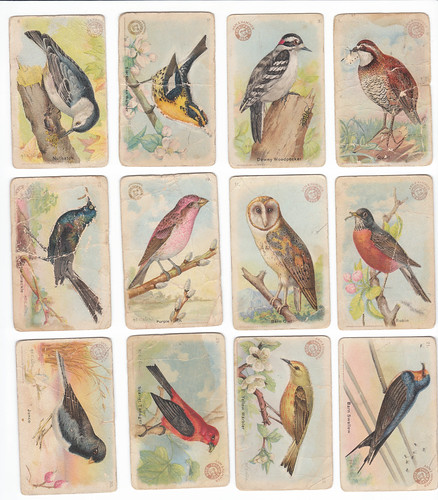

Last week some wonderful people who were along on most of our spring warbler walks, Don and Lynn Watson, sent me an unexpected gift—a little package of 51 bird trading cards. Most were from the Dwight & Church Company—the cards had been placed in packages of Arm & Hammer Baking Soda produced in New York..

The moment I saw them, oddly enough, I thought of Carrol Henderson’s wonderful book,

Oology and Ralph’s Talking Eggs: Bird Conservation Comes Out of Its Shell, a superb book about the history of bird conservation that Henderson wrote after he spent time with a family friend examining the egg collection of the friend’s great-grandfather, an Iowa farmer named, Ralph Handsaker. I couldn’t remember why these trading cards made me think of a book about a very old egg collection, so I pulled out the book, and voila! In Chapter 3:

Many egg clutches preserved in Ralph Handsaker’s egg collection contained an Arm and Hammer trading card for that species of bird. There were lots of those cards. Ralph must have gone through a lot of baking soda.

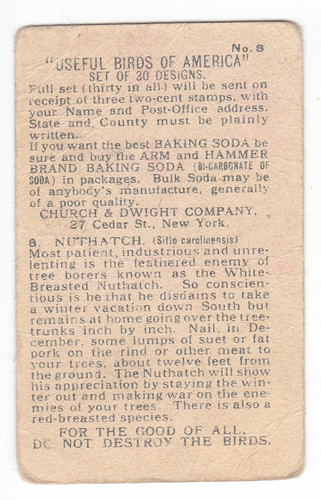

In the 1880s, the Church and Dwight Company of New York began a corporate tradition that lasted nearly ninety years—bird trading cards. These colorful cards originally came in Arm and Hammer Baking Soda boxes, and later they could be ordered by mail. At a time when many wild birds were being killed for their meat and feathers, the Church and Dwight bird cards featured the theme of “Useful Birds of America” and a simple message: For the Good of All, Do Not Destroy the Birds.” Each card carried a short, interesting paragraph about the natural history of the bird portrayed. The account for the Blue Jay in the New Series of Birds (number 5) in 1910 states: “This naughty bird has a fondness for eggs and nestlings, but his jaunty reckless air does much to make men overlook his shortcomings.”

The first series of cards in the 1880s included sixty “Beautiful Bird” cards. This series was followed by nearly twenty-four sets of cards that included from fifteen to thirty cards, each from 1904 to 1976. They featured game birds, songbirds, shorebirds, and birds of prey. These cards were coveted both by children and adult bird enthusiasts. Across the country, they served both as collector cards and as America’s first handy references for identifying wild birds.

The Church and Dwight Company commissioned one of the greatest bird artists of all time to paint ninety species for use on some of their cards—Louis Agassiz Fuertes. … Interestingly, Fuertes’s paintings of birds of prey were placed in a vault and not published because of the negative views held by the public for birds of prey in the early 1900s. As a way of commemorating the nation’s bicentennial, the Church and Dwight Company published one last set of cards in 1976—a stunning selection of ten hawks, owls, and the Bald Eagle by Fuertes.

(I happen to have bought that set that year: the set of ten beautiful cards cost 35 cents and a box top from Arm & Hammer baking soda.)

Henderson mentions some other companies inspired by the Church and Dwight Company to create their own sets of bird cards. Starting in 1898, the Singer Sewing Machine Company started producing large format cards portraying songbirds with an inset of a life-size drawing of each species’ egg. The back of each card gave some natural history information about the bird as well as promotional information about Singer’s sewing products. Carrol Henderson also discusses some companies that produced similar bird cards outside America, including the Red Rose Tea and Coffee Company in Montreal—the set of bird cards Don and Lynn sent me included three of those, produced between 1951 and 1955. The National Wildlife Federation was involved in production of those, and they were illustrated by Roger Tory Peterson.

My dear neighbors Bob and Mary Tonkin gave me a very old card from the Arm & Hammer series, a “Crested Titmouse” (either our Tufted Titmouse or the Black-crested Titmouse). It doesn’t have a date on it, but the layout style was different and seems older than the ones from Don and Lynn. The artist signature seems to read “Bufford.”

The back of the original card reads:

This handsome Bird Card though designated by a number has no connection with any lottery and does not draw any prize. The perfect quality of the Arm and Hammer Brand of Soda and Saleratus is sufficient inducement for all intelligent consumers to buy ONLY that Brand.

A set of these cards (SIXTY in all) accumulated in the ordinary course of buying housekeeping supplies will form an interesting collection. The enormous expense of putting a card in each package of our Soda and Saleratus prevents our furnishing each one of the many thousand applicants with an entire set free. Should all the cards be desired immediately a dime or five two cent postage stamps will about pay the cost and postage and upon its receipt with your Post Office address we shall be pleased to mail a complete set of the cards.

Your truly,

Church & Co.

The one that appears to be the next oldest vintage, the one called “White Bellied Swallow,” (probably our Tree Swallow) has neither a date nor an artist’s name. Now the company asks for six two-cent stamps for a set. It adds a new advertising text:

IMPORTANT REASONS why housekeepers should be package soda in preference to bulk soda weighed and wrapped by the dealer. The retail price of the Arm and Hammer Brand of soda in packages is the same as for inferior package soda. Consumers gain nothing by buying unknown and inferior soda, they simply put more money into the merchants’ pockets. Package soda like Church & Co’s Arm & Hammer Brand has the guarantee of a responsible manufacturer. Bulk soda may be of anybody’s manufacture and generally of a poor quality.

The next batch also lack a series number, but these all have a copyright inscription below the drawing—I think they all read 1915. This is where the company name changes from Church & Co. to Church & Dwight Co. I could read just a few with a magnifying glass, but when I scanned them at the highest resolution my trusty old scanner can do, 600 dots per inch, and zoomed in, I could read most of them pretty clearly. The artist signature is of M.E.Eaton.

M.E. Eaton also did a set of these cards called “The Second Series” bearing a 1918 date and “The Third Series,” from 1922.

I didn’t have a clue who that could be, so I googled the name. She is Mary Emily Eaton, born in the U.K. in 1873 and best known as a botanical illustrator. She came to New York to work for the New York Botanical Garden in 1911. In the several articles I found about her, I didn’t see any reference to her illustrating these Arm and Hammer cards, which were all produced during her time in New York. Her gorgeous plant illustrations, produced in much larger formats, were what she was famous for. She lost her job at the botanical garden in 1932 during the Depression, and had a horrible time finding enough work to support herself, especially due to the severe paper shortages during the war. She returned to the UK in 1947.

Starting with the Second Series, the backs of the cards started including basic information about the bird depicted.

On the one titled "Nuthatch," showing the White-breasted Nuthatch, the card reads:

Most patient, industrious and unrelenting is the feathered enemy of tree borers known as the White-Breasted Nuthatch. So conscientious is he that he disdains to take a winter vacation down South but remains at home going over the tree trunks inch by inch. Nail, in December, some lumps of suet or fat pork on the rind or other meat to your trees, about twelve feet from the ground. The Nuthatch will show his appreciation by staying the winter out and making war on the enemies of your trees. There is also a red-breasted species.

So far I haven’t been able to find out who contributed the bird information for the cards, but starting with this series, every card I have from then on also includes the message, “FOR THE GOOD OF ALL, DO NOT DESTROY THE BIRDS.”

I showed all these oldest cards to my 98-year-old mother-in-law, who loved seeing things that are all older than she is.

The ninth and tenth series cards were illustrated by Louis Agassiz Fuertes. These don’t have a copyright date. According to the Birds of Prey cards released in 1975, Charles T. Church, a naturalist in his own right as well as being a senior member of the board of Church & Dwight, commissioned Fuertes in the early 20s to produce the artwork for 30 songbird and 30 game bird species—those cards were published at various times through 1964. Fuertes also produced 30 more, including the 10 Birds of Prey cards released in 1975, all before he died in a car crash in 1927.

Back in the 1970s, when the public was very concerned about environmental issues and Carol Burnett ended almost every one of her programs with a little anti-pollution message, McDonald's produced an amazing set of teaching materials, including overhead projector transparencies, ditto masters, and other media to give teachers a solid teaching unit about basic principles of ecology. I got the set for free and used it a lot when teaching junior high science. Lots of other corporations were also capitalizing on such widespread support for protecting the environment. Sometimes it felt hypocritical, but in the case of those Birds of Prey cards, Church & Dwight had a very long and honorable history of providing wonderful educational materials. I don't know if there is another brand of baking soda, because I'd never ever consider buying anything but Arm & Hammer. And now I have even more reasons for brand loyalty.