|

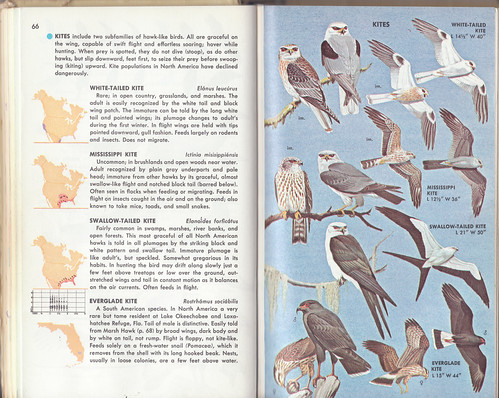

| My original Golden Guide showing the Everglade Kite |

When I started scrutinizing my field guides as a brand new birder, one of the birds I quickly became obsessed with trying to find was the Everglade Kite. I was intrigued with the very idea of calling any raptor a “kite,” so obviously had to look up the etymology: “kite” comes from Middle English, from Old English cȳta; akin to Middle High German kūze for owl. That struck me as especially odd, because owls are rather sedentary or, when they do fly, have a direct flight, while as a verb, one definition of “kite” is, “ to go in a rapid, carefree, or flighty manner.”

That intrigued me, but even so, I doubt if I’d have become obsessed with the Everglade Kite if I hadn’t read the species entries about it. The Golden Guide said that it was very rare but tame—that sounded like a cool combination—and “Feeds solely on a freshwater snail (Pomacea), which it removes from shell with its long hooked beak.” Imagine a beautiful hawk that eats just one thing—a big snail—and has an amazingly curved, sharp bill pretty much worthless for anything except pulling out the snail innards from the shell. Of course I wanted to see one.

The description left me puzzled, too, because it also said of the Everglade Kite, “Flight is floppy, not kite-like.” Since it was a kite, wouldn’t its flight be the very definition of kite-like flight? But I quickly learned that some of the birds called kites, such as the Swallow-tailed Kite, belong to entirely different genera than the Everglade Kite—some authorities even put them in different subfamilies.

I never did see an Everglade Kite before the American Ornithologists’ Union changed its name, in 1983, to the Snail Kite—the name already used for the same species where it lives in the Caribbean and Central and South America.

|

| My son Tommy at the Anhinga Trail in the Everglades in 1988 |

|

| Snail Kite (near the center of the photo) in Mexico |

Then last month Russ and I went down to Florida for a few days. Part of our plan was to get down to the Everglades. I knew that Snail Kites are supposed to be easier to find now, but I intended to take a swing along the Tamiami Trail again for old times sake. Unfortunately, our trip was cut short and we never got out of the Orlando area. We spend the last morning at a little urban park just outside downtown Kissimmee—Brinson Park on Lake Tohopekaliga—to see what we could. Even before the sun had risen, a stunning adult male Snail Kite flew right past us and landed in a nearby tree, close enough that even my little dog Pip took notice.

Like my trusty old Golden Guide said but I’d never before experienced, it really was tame. The low light made for low quality photos, but the close distance almost made up for that. I got to enjoy him for several minutes before he finally took off. Twenty minutes or so later, I spotted one way out in the shallow lake, sitting on a sign.

I spent a lot of time watching Limpkins searching for and eating apple snails—that relative of cranes happens to be another snail specialist.

And suddenly I noticed an adult male Snail Kite, possibly the same one as earlier, on a nearby power line over a sidewalk, with people running and walking along right below it. By now the sun was high enough to provide perfect lighting, and the bird tame enough to let us get close for full frame photos.

|

| My original digiscoped Limpkin photo from 2005 |

South American apple snails entered the ecosystem mainly via the aquarium trade. As with Burmese pythons and other snakes that have become a scourge in the Everglades, some exotic apple snails are released by pet owners who can’t take care of them anymore, but also, as with those snakes, large numbers were flooded out of containers and warehouses at large-scale dealers during Hurricane Andrew and other massive storms.

By 2010, as one South American species of apple snail started appearing in huge numbers in the Everglades, birders and bird conservationists were thrilled that it could serve as an additional source of food for the Snail Kite, which is a federally listed endangered species. After all, Snail Kites of South America, belonging to the same species as ours, feed primarily on those south American apple snails. That's a good thing, right? Sure enough, the kites devoured these snails and their population is now surging. This seemed absolutely wonderful, and has been giving many birders the same delightful encounters I enjoyed last month at Brinson Park. What could possibly be bad about that?

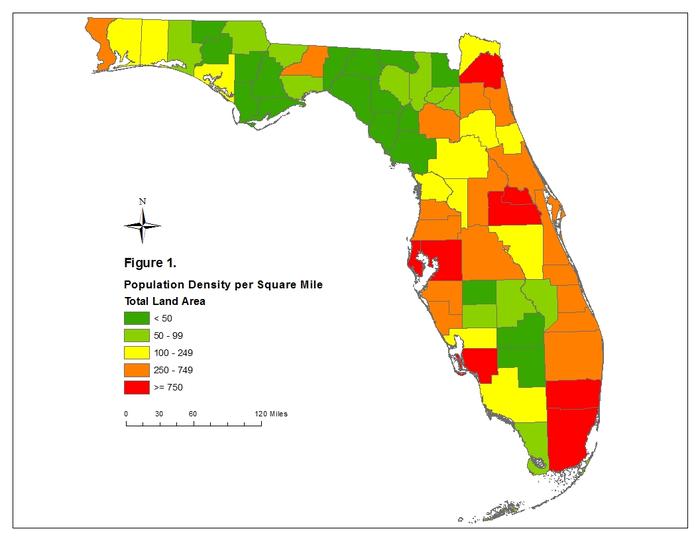

Back in 1988 when I lucked into seeing my first Snail Kite, my family took a tram ride tour of the Everglades with a superb National Parks guide. We got to touch sawgrass—the basis of much of the unique and vulnerable ecosystem of the Everglades—and we learned how all the nutrient discharge—from agriculture, golf courses, lawn fertilizers, and sewage from swelling cities and theme parks—flowed directly into the Everglades, fostering algal blooms and excessive growth of certain plants, like cattails, at the expense of the native sawgrass and the species specially adapted to the unique Everglades habitat. It all sounded very depressing—Florida's ever-growing human population seemed to mean certain death to the Everglades, sooner rather than later.

|

| Florida's growing human population |

There have been lots of news stories in the past decade about finally finding a strategy to reduce the discharge of all that sewage and fertilizer into the Everglades. The new plan has been to develop special marshes with plants chosen to absorb the nutrients before they can flow into the Everglades.

Now suddenly all that hopeful work is in jeopardy, and all because of those South American apple snails. One might think that all the apple snails belonging to Pomacea would be pretty much alike, and that seems to be the opinion of the Snail Kite and Limpkin.

But it turns out that the South American apple snails devour rooted plants rather than loose material and scum. Even as their presence has dramatically boosted numbers of Florida’s Snail Kites and Limpkins, they’ve exacted a huge toll on the overall health of the ecosystem. In 2014, hordes of them devoured much of the vegetation in a 750-acre man-made marsh designed to filter phosphorous out of the Everglades. At this pace, they pose a serious threat to the rest of the 57,000 acres of marshes built at a cost of $2 billion to rid the fragile wetland of agricultural and sewage runoff. Because of those exotic apple snails, the Everglades are in as much jeopardy as ever.

In 2010, Florida Audubon successfully lobbied the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission to hold off reducing the exotic snails in order to help the Snail Kite. The Everglade Snail Kite is still listed as endangered in the U.S. even as it’s doing just fine in the rest of its range.

The apple snails native to South and Central America are in balance with the natural vegetation there, and snails and kites are thriving. But that’s an entirely different ecosystem than our unique and precious Everglades, which are so dependent on our native sawgrass. It’s quite possible that our natural population of Snail Kites was always limited in our system. Now that we know the horrible impact exotic snails are having on the Everglades ecosystem, we need to work together, not pitting bird lovers against ecosystem conservationists. We must find long-term solutions that can protect our unique River of Grass and keep our precious Snail Kite at healthy, even if once-again smaller, numbers.

Meanwhile, as we try to find effective but safe ways of curbing the snail numbers, Limpkins and Snail Kites are doing their part by pigging out on the South American snails. If we solve the problem, their numbers will inevitably shrink as they return to their more limited natural food supply.

I only hope we birders can keep the long view, understanding the natural systems at play here and how very much is at stake. It was so thrilling for me to spend such quality time with two of my favorite birds—the two species that relish apple snails. I very much want other birders to get to enjoy that, too. But I hope and pray that this kind of pleasure for us doesn’t get in the way of protecting the very habitat that brought Snail Kites to Florida in the first place.