|

| Hiking in the Chiricahuas |

In 1982, Russ and I took our 6-month-old baby Joey to Arizona. One of the highlights for me was a long hike in the

Chiricahua Mountains, where I saw my lifer

Mexican Chickadee.

This species isn’t particularly rare within its range, but only reaches the United States in a few places. The most accessible area, where most birders add it to their lifelist, is along the trails near the Rustler Park campground; sure enough, that’s exactly where we saw it. The hike was so fun that the day remains one of my favorite memories—that was the day we even came upon a Gila Monster. I can’t remember the exact moment I saw my lifer Mexican Chickadee—it was just one of many lovely experiences that day. So as thrilled as I was to have finally seen the last of all the chickadees that breed in the Lower-48, I’m afraid it didn't qualify as a “Best Bird EVER!”

Then, in 2013 I did a Lower-48 Big Year, and one of my goals was to see every chickadee in that one year. That meant I had to head back to the Chiricahuas to see the Mexican Chickadee again.

Unfortunately, my Big Year plans had to be abbreviated, in terms of both time and money, and I didn’t get to the Chiricahuas until November 23. I’d made arrangements to stay for two nights at the legendary

Cave Creek Ranch so I’d have a whole day to enjoy the high elevations where the chickadee would be. I reached the entrance to the ranch at mid-afternoon, when we were getting a few snow flurries. The dirt road in had a warning sign, “SERIOUS BUMP,” but with due diligence, I got my low-carriage Prius through it just fine.

While planning my trip to the extreme south, close to the Mexican border, it never occurred to me that I might need winter boots, a shovel, and sand or kitty litter, much less snow tires on my car. I had plenty of warm clothes but had not thought to prepare for winter driving, which was especially shortsighted because I'd be driving all the way home to northern Minnesota as Thanksgiving approached, when snow is just about always expected. There were a few small bits of snow here and there in the vegetation as I drove to Cave Creek Ranch, and a more thorough dusting covering the ground at the ranch, but I figured that was the most I’d see down there. I didn’t have enough time to get up into the mountains that day, and so I spent the rest of the afternoon reveling in and photographing feeder birds and javelinas, also called collared peccaries, at the ranch.

When it got dark, I had a wonderful dinner and went to bed early. I had an exciting full day of birding ahead.

I woke at first light to two or three inches of snow on the ground, as beautiful as it was disconcerting. My car could easily handle that even without snow tires if I took it slow and easy, but I knew that the snow depth would increase as I went up the mountain, and I needed to be at a much higher elevation to see the chickadee. To be on the safe side, I waited a couple hours before I set out, in hopes that the road up the mountain would get plowed out. Meanwhile, I looked at an assortment of birds I’d always associated with hot, dry Arizona—it was unsettling to see them in snow, but of course it snows in winter, at least sometimes, even down in Arizona and Mexico.

|

| Painted Redstart |

|

| Pyrrhuloxia |

|

| Mexican Jay |

|

| Blue-throated Hummingbird |

When I finally set out, the roads hadn’t been touched by plows or other vehicles. It was easy to stay on the road, but sure enough, the snow got deeper and deeper as I climbed. I’ve done plenty of driving in snow over the years, and for a few miles worked my way slow but steadily up the road. I passed the Southwestern Research Station—closed to visitors for the season—and made it a total of about seven miles. I didn't get quite to Paradise Road, and still was a full six or seven miles short of where Russ and I had seen Mexican Chickadees before, up in Rustler Park. I'd crept along as the snow got deeper and deeper, until at last it was up to my front bumper and my car couldn’t go any farther.

It was time to give up. I had to leave the Chiricahuas the next morning, so I was giving up on my one and only shot at Mexican Chickadee for the year.

I didn’t have leisure to feel sorry for myself—I still had to figure out how to turn my car around in the deep snow to head back down the mountain. All I could do without a shovel was to kick away a path through the snow in front of all four tires, wearing my hiking boots, and then get back in the car and try to inch it around in a U-turn. I managed to move the car a couple of feet before I got mired again. I got out, again kicked away snow to make another short path, and again worked the car a couple of feet further. The morning was silent, the thick snow beautiful even if it was creating a worst-case scenario for birding. There was no wind and it wasn’t all that cold—probably low- to mid-20s—but there were also no birds calling. I was just as glad about that because I was focused on kicking away snow. I wasn’t all that upset—when I’m alone, with no one else depending on me, I can be surprisingly Zen-like in dealing with setbacks.

It took three or four more kicking-snow-and-inching-my-car-forward episodes to get my car perpendicular to the road. I had to kick out the snow from in front of my tires and inch the car forward another five or six times before it was finally facing the right direction, down the mountain instead of up. I’d spent more than 45 minutes at it, and despite my warm coat, hat, and gloves, I was chilled to the bone, my feet frozen. I cleared out enough snow ahead of my tires to get a three or four-foot start in hopes that I could stay in motion going straight down—at least now I could drive in the tracks I'd made going up.

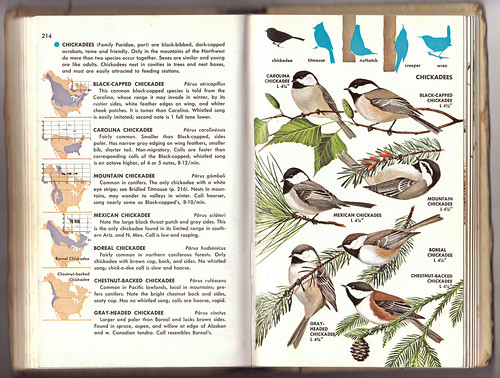

I had just opened the car door to get in for the last time when suddenly I heard the rapid chickadee calls of a Mexican Chickadee! I thought it was my imagination—how could it not be? But no, there in a conifer next to the road was a chickadee staring at me. I’d kept my binoculars on while driving and then while shoveling, so I got a clear look at the extensive black bib and distinctive gray wash on the sides. A Mexican Chickadee!

Like other chickadees, Mexican Chickadees tend to move about in winter flocks, but as hard as I looked and listened, I could not find another chickadee, or any other bird for that matter. I'd been pretty quiet with my kicking and inching my car, a hybrid without any engine start-up noise, but birds have keen hearing. Perhaps this little guy heard an odd sound and flew down the mountain to check it out, or perhaps it took pity on a poor, wayfaring stranger a’traveling through that world of woe. I’ll never know what impulse brought it to me or made it call at quite literally the last possible second before I started down the road. It flew away before I could even think to get my camera out of the car. But for one brief, shining moment, which was all I really needed, there it was. That Mexican Chickadee was surely my best bird EVER.