Whenever Snowy Owls appear in the Lower 48 States, people get excited. Snowy Owls are magnificent—so superlative in every way, and so tied in with popular culture thanks to Harry Potter’s Hedwig—that any report attracts birders, photographers, and a lot of people who otherwise aren’t even interested in birds.

When I started birding and took my first ornithology class in 1975, I learned that Snowy Owls are non-migratory arctic birds that retreat south only when the population of their dietary staple—lemmings—crashes. We were taught as fact that few if any of the ones we see in the south manage to return to the Arctic, and that most or even all of them are starving.

This was probably a fine working hypothesis, but has been thoroughly disproved. David Evans started banding and following Snowy Owls in the Duluth-Superior Harbor in 1973. He is a co-author of the newly revised Snowy Owl entry in the Birds of North America, published by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the American Ornithologists’ Union. David found that Snowy Owls were successful at hunting in our area, and over the years, he learned that some banded individuals returned two, three, or even four years in succession. Results of his work weren’t disseminated far and wide—he started long before social media was in the picture.

Snowy Owls also often appear on airport runways—an expanse of open land visually similar to tundra. Logan International Airport worked out with Massachusetts Audubon and bird banders a project for capturing and removing these owls to safer places. This program has also provided data about the birds’ health and verified that many of them do just fine down here, and some return year after year. But again, word of this didn’t get out with regard to the overall health of Snowy Owls in many years, and people continued to believe that most or all of the Snowy Owls that appear down here are weakened and emaciated.

During the significant Snowy Owl “invasion” during the winter of 2013-14, some researchers banded together to affix GPS transmitters on some Snowy Owls to follow their individual movements in a project they cleverly named Project SNOWstorm. Some of these researchers are well known in both the birding community and the larger world. Any huge research project about such a popular and charismatic species, with such charismatic and media-savvy researchers trying to garner essential funding is going to catch the public eye, and is going to be covered by the news. This has been a Good Thing.

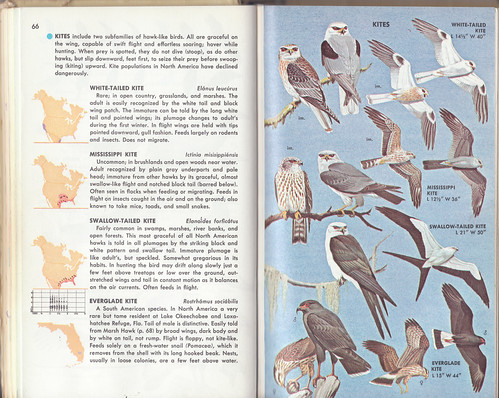

|

| A healthy Snowy Owl being tracked by David Evans in Superior, photographed this January. |

Snowy Owls also often appear on airport runways—an expanse of open land visually similar to tundra. Logan International Airport worked out with Massachusetts Audubon and bird banders a project for capturing and removing these owls to safer places. This program has also provided data about the birds’ health and verified that many of them do just fine down here, and some return year after year. But again, word of this didn’t get out with regard to the overall health of Snowy Owls in many years, and people continued to believe that most or all of the Snowy Owls that appear down here are weakened and emaciated.

During the significant Snowy Owl “invasion” during the winter of 2013-14, some researchers banded together to affix GPS transmitters on some Snowy Owls to follow their individual movements in a project they cleverly named Project SNOWstorm. Some of these researchers are well known in both the birding community and the larger world. Any huge research project about such a popular and charismatic species, with such charismatic and media-savvy researchers trying to garner essential funding is going to catch the public eye, and is going to be covered by the news. This has been a Good Thing.

The trick is that when they got the word out that, during the first two years they were working on this, the birds they were handling were mostly in great shape, the media and many birders jumped to the conclusion that all or most of the Snowy Owls that appear down here from year to year are healthy. Ironically, some self-serving photographers using unethical methods such as baiting Snowy Owls to draw them closer, birders getting too close when chasing down lifers, and bird guides bringing hordes of other people to see them, had long been justifying their actions by claiming that the birds were doomed anyway, so if a bird died as a result of their activities—well, it was going to be dead soon anyway. Now they took a 180-degree turn, saying the birds are perfectly healthy, so there's no reason to worry about disturbing them.

It’s of course true that Snowy Owls need fuel to make such a long, arduous journey in the first place, so they must have had at least some successful hunting along the way, but it’s also true that individual migrants of all kinds of species use up all their physical resources making a long flight, and some end up utterly depleted and dying.

Rehabbers have long known that many or even a majority of the Snowy Owls that are brought to them in some invasion years are significantly below normal weight. Some are, indeed, starving. This can be a secondary result of injury, pesticide exposure, disease, or other problem associated with a long journey and trying to hunt in unfamiliar territory. Once they arrive, some individuals can’t get enough food, sometimes because there isn't enough food available, sometimes because they cannot find a safe place to hunt alone (Peregrine Falcons, ravens and crows, and acquisitive birders and photographers displacing them), and sometimes because the long, arduous journey through unfamiliar areas simply did in a very old or very young bird. But in some years it happens like people used to think it always happened—lemming populations do crash periodically, and those years are, indeed, sometimes associated with both “owl invasions” and a large number of starving owls.

It’s of course true that Snowy Owls need fuel to make such a long, arduous journey in the first place, so they must have had at least some successful hunting along the way, but it’s also true that individual migrants of all kinds of species use up all their physical resources making a long flight, and some end up utterly depleted and dying.

Rehabbers have long known that many or even a majority of the Snowy Owls that are brought to them in some invasion years are significantly below normal weight. Some are, indeed, starving. This can be a secondary result of injury, pesticide exposure, disease, or other problem associated with a long journey and trying to hunt in unfamiliar territory. Once they arrive, some individuals can’t get enough food, sometimes because there isn't enough food available, sometimes because they cannot find a safe place to hunt alone (Peregrine Falcons, ravens and crows, and acquisitive birders and photographers displacing them), and sometimes because the long, arduous journey through unfamiliar areas simply did in a very old or very young bird. But in some years it happens like people used to think it always happened—lemming populations do crash periodically, and those years are, indeed, sometimes associated with both “owl invasions” and a large number of starving owls.

This year Snowy Owls are already being reported in big numbers in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. David Evans, the researcher who has been banding them in the Duluth-Superior area for over 40 years, brought one emaciated bird to Peg Farr, director of Duluth’s Wildwoods Wildlife Rehabilitation Center, and told her that in his experience, in years when owls first start appearing in November and December, most of them are healthy, but when they first start appearing in October, he’s long noticed that many of them are stressed, injured, or even starving.

This is the tenth autumn in which Peg has been taking in birds, but just the first October in which she’s had to deal with Snowy Owls—and she’s had three already. As far as she could judge by plumage and size, all were young males. And each weighed less than 900 grams—that’s less than 2 pounds, when healthy males should weigh 3 ½ pounds. Marge Gibson of the Raptor Education Group, Inc., in Antigo, Wisconsin, has received four so far, one dead on arrival. One young male weighed an astonishing 815 grams—only 1.8 pounds. And a young female weighed 1000 grams, or 2.2 pounds, when healthy females should weigh more than double that. Marge had news of seven others that were found dead in fields.

|

| One of the emaciated Snowy Owls at Wildwoods. On the outside, they can appear fit and healthy even when they weigh less than half a healthy weight! |

Marge and Peg post information about the animals they’re treating on their blogs, and Marge also posts on the Wisconsin Birding Facebook page. Instantly, people who have been keeping abreast of developments for Project SNOWstorm were sending these experienced and knowledgeable wildlife rehabilitators cranky and sometimes outright rude messages that it’s a “myth” that owls are starving, even as Marge and Peg could feel in their own hands the atrophied breast muscles and exposed keel bone beneath the feathers of obviously emaciated birds.

These people were parroting a warped interpretation of the great new information Project SNOWstorm has been gathering. Scientists tracking healthy Snowy Owls in the past two years have proven that many of the ones that retreated down here were healthy. Of course, those two years happened to coincide with an abundance of food on the tundra. Project SNOWstorm necropsies on tracked owls that died showed that they'd been killed due to clear factors other than starvation.

The old conventional wisdom that all the Snowy Owls that appear down here are starving has long frustrated me, and I'm glad Project SNOWstorm has had the public forum to clear that up. But the new conventional wisdom—that they’re never starving—is equally incorrect.

The old conventional wisdom that all the Snowy Owls that appear down here are starving has long frustrated me, and I'm glad Project SNOWstorm has had the public forum to clear that up. But the new conventional wisdom—that they’re never starving—is equally incorrect.

There’s an old fable about blindfolded people examining an elephant, each learning a vast amount of information about one tiny part, and each coming to an entirely different conclusion about the entire animal. Rehabbers and field biologists each have specific areas of expertise with little overlap. It will take open sharing of information between them to clear this up.

In my experience, most rehabbers know a lot about wild birds, and are extremely happy to get more information from field people—it helps inform their treatment so they can provide as much of a natural diet and environment as possible. Meanwhile, more and more field biologists are pooh-poohing the work of rehabbers, and ignoring the wealth of information they could be providing. Some field biologists believe that helping individual animals is worthless from a conservation standpoint and takes valuable energy and resources from work that helps whole populations. Others discount the value of individual animals altogether.

My own background as a rehabber certainly gives me a bias, but objectively, rehabbers have furnished invaluable information and services essential in reintroduction programs for endangered species. Their observations about animal behavior and adaptability have helped inform our increasing understanding of avian intelligence. Techniques they refine inform the care given to animals by laboratory biologists. Rehabbers are required to keep statistics about the weight and condition of animals on admission, and what circumstances led to their being admitted. Because they receive so many birds from diverse segments of the general population, their data can furnish a lot of valuable information about “birds in trouble,” providing an important early warning system regarding pesticides and other dangers.

Rehabbers and field biologists have both been essential partners in discovering virtually everything we know about lead poisoning—a huge conservation issue for waterfowl, including Trumpeter Swans, and raptors, including Bald Eagles. Rehabbers were in the first line of defense in figuring out which species were most vulnerable to West Nile virus.

And in the peculiarly complicated case of Snowy Owl movements, statistics regarding the differences in the timing and birds’ condition on arriving at rehab centers from year to year can help fill in some of the many holes in our understanding of the birds’ situation in different kinds of invasion years.

Rehabbers and field biologists have both been essential partners in discovering virtually everything we know about lead poisoning—a huge conservation issue for waterfowl, including Trumpeter Swans, and raptors, including Bald Eagles. Rehabbers were in the first line of defense in figuring out which species were most vulnerable to West Nile virus.

And in the peculiarly complicated case of Snowy Owl movements, statistics regarding the differences in the timing and birds’ condition on arriving at rehab centers from year to year can help fill in some of the many holes in our understanding of the birds’ situation in different kinds of invasion years.

And there are, indeed, different kinds of invasion years. In normal years, a Snowy Owl’s clutch size averages 3¬–5. When food is plentiful, it’s 7–11. We get “invasions” when food and production of young owls are abundant, such as in 2013. In those years, many or most of the birds seen by birders are in fine fettle. Young males in particular were probably driven south not by food needs but by territorial adults driving them out of their normal range. But we also get invasions in years after the lemming population crashes, while the Snowy Owl population is still near peak even with low reproduction, when some may indeed be driven south by hunger. That may be happening this year.

And of course, in any kind of year, as field biologists such as David Evans, working the same winter areas year after year, decade after decade, have long known, some individual Snowy Owls migrate to the same wintering areas regularly.

Understanding Snowy Owl movements is also complicated by simple geography. Birds found along the eastern seaboard may have moved a thousand miles or more along fairly open, tundra-like habitat, while those arriving in the Midwest may have crossed a thousand miles of dense boreal forest—an inhospitable habitat for a species adapted to hunting in open country.

So Snowy Owls make for one complicated elephant!

Science is supposed to be about amassing as much information as possible to provide comprehensive and nuanced answers to our questions, not about limiting what questions we're allowed to ask or limiting how we answer them based on what one group of scientists wants to focus on. Some field biologists do stay abreast of what rehabbers are encountering, but many don’t, and some are disturbingly patronizing or even insulting to rehabbers. That must end.

It would be the natural impulse of someone who has spent the past two years handling healthy owls to say the owls going to rehabbers now must have been injured or exposed to pesticides to have reached an emaciated state, and are not truly “starving.” But rehabbers do necropsies, and do not report “starvation” as a cause of death in even a severely emaciated bird if any evidence of a precipitating cause is found. This year, rehabbers are experiencing a different phenomenon than in the past two years. Figuring out the complexity—looking at lemming populations and gathering other data about what's happening on the tundra for example—rather than digging in heels about preliminary findings of what is so far a short-term, 2-season research project, should be our goal.

It would be the natural impulse of someone who has spent the past two years handling healthy owls to say the owls going to rehabbers now must have been injured or exposed to pesticides to have reached an emaciated state, and are not truly “starving.” But rehabbers do necropsies, and do not report “starvation” as a cause of death in even a severely emaciated bird if any evidence of a precipitating cause is found. This year, rehabbers are experiencing a different phenomenon than in the past two years. Figuring out the complexity—looking at lemming populations and gathering other data about what's happening on the tundra for example—rather than digging in heels about preliminary findings of what is so far a short-term, 2-season research project, should be our goal.

When Project SNOWstorm was inaugurated and so successful in tracking birds, it was news to a lot of people that many of the birds trapped were healthy and plump to begin with and stayed so over the season. In getting the word out about this, their news that "Owls aren't starving!" has been as egregiously overstated or misinterpreted as the old myth that "Owls are starving!" With this year’s early appearance of Snowy Owls, Project SNOWstorm has been hoping to get reports of birds that bear their GPS transmitters, and is also hoping to affix some devices to healthy birds to track. Meanwhile, rehabbers are handling unusually large numbers of severely emaciated birds. Just remember: Project SNOWstorm's job is to track healthy owls. REGI, Wildwoods, the Raptor Center, and other rehab facilities have the job of taking care of the owls that aren't doing well. Those of us who are concerned about the birds and interested in their basic natural history should be thrilled to be getting information from both avenues of discovery.

Using data from ALL professional researchers dealing with Snowy Owls, including field biologists and banders here and on their breeding grounds, scientists associated with Project SNOWstorm, and rehabbers, we will eventually tease out what Snowy Owl movements are all about. For those of us who love working out complicated answers to complex puzzles, this is good news. For those who love sound bytes or have an emotional response against bird research in one form or another, this isn’t such good news. Writing click bait headlines on internet sites (Owls are starving! Owls aren’t starving!) is a profoundly anti-science impulse—something all of us who trust science and want complete answers to our questions should firmly squelch.