In November 1988 when my children were still little, Russ had a meeting in Washington, D.C., so we planned a family adventure around it, using up Russ's vacation time to drive to D.C. and then, after the meeting, going on to Florida. That trip is still brought up in family lore—we visited the National Zoo and a lot of the memorials and museums in D.C., went to Disney World and Sea World, and camped for a few nights in the Florida Everglades.

When we got home, the very first stories the kids poured out to Grandma and Grandpa weren’t about theme parks or pandas or touching a piece of the moon—their most vivid memories were our adventures in nature—Thanksgiving dinner cooked on a campfire and eaten in our tent in the Everglades, the frogs and toad in the campground bathroom, and the birds and alligators we saw along the Anhinga Trail. They told about playing and swimming with Daddy on Cocoa Beach while Mommy spent the entire time looking out on the ocean through a spotting scope—that’s when I saw my lifer Northern Gannets. I’d been an avid birder for over a decade before that trip, but added several other lifers, too, including my first Wood Stork, Limpkin, and Mangrove Cuckoo.

While we were planning the trip, one of the things we hoped to do was bring the kids to see my mother in Fort Lauderdale. I called her ahead of time to say we were coming and would love to see her and take her out to dinner—she hadn’t seen the kids since Joey was a toddler and Katie was a baby, and she hadn’t even seen Tommy yet—but she hung up on me. I was devastated, and Russ called the little ones over and explained that my mother was not a kind person, but that our real family—Grandma and Grandpa and Auntie Jeanie and Muncle Mike—loved them very much. Tommy was too little to understand, but 7-year-old Joey cried because his "other Grandma" didn’t want to see him. Katie focused on something else—she came running to me and threw her arms around my neck and said (and this is an exact quote), “Oh, my dear sweet Mommy. How did you learn to be a kind mommy when you didn’t have a kind mommy to teach you?”

That was an astonishing thing for a four-year-old to say, and at the time, all I could do was hug her. But when I think about it, I realize there was a very simple answer to her question. Everything I knew about being a kind mommy I learned from Fred Rogers.

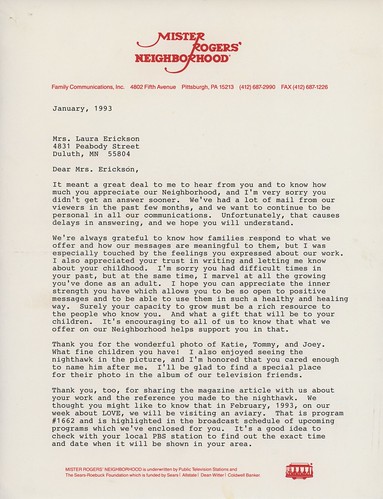

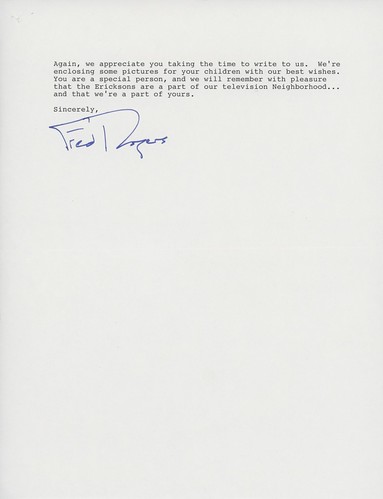

From the time Joey was a baby, I’d been watching Mr. Rogers' Neighborhood every day. His warm and calming demeanor was balm to my soul, and little by little he brought light and fresh air into the darker regions of my heart and healed the bruises I didn’t realize were still there from my battered childhood. One of my most treasured belongings is a personal letter he sent me back in 1993.

I’ve been thinking about Mr. Rogers a lot lately, thanks to a recent documentary and an upcoming film about him. And of course people post his words in the aftermath of hurricanes and other natural disasters. But his words appeared on Facebook and other social media even more than usual after last week’s three horrifying white supremacist terrorism attacks. People all over the internet were quoting Mr. Rogers’s famous line, “Look for the helpers.” Rogers wrote:

When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, "Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping." To this day, especially in times of "disaster," I remember my mother's words and I am always comforted by realizing that there are still so many helpers – so many caring people in this world.Rogers's words were not written to comfort adults—he was telling us how to explain scary things to children. He said that children “need to hear very clearly that their parents are doing all they can to take care of them and to keep them safe.”

Few people seem to realize that the underlying context is that the adults are supposed to BE the helpers. My daughter grasped that concept and assumed the helper role herself when she was four years old, but more and more of the problems we’re facing right now, from that horrifying rise in white supremacy to the climate change that is exacerbating storms, are not being addressed by adults.

Indeed, right now it’s children who are stepping up to the plate more than adults to be the helpers with regard to climate change. In a lawsuit filed in 2015 during the Obama administration, 21 children and adults, aged 11 to 22, accused the federal government of violating their due process rights by knowing for decades that carbon pollution poisons the environment, but doing nothing about it. They’re seeking various environmental remedies, all of which would improve air and water quality even beyond climate effects.

Their lawsuit, titled Juliana v. U.S., had been scheduled to begin in U.S. District Court in Oregon on Monday before it was temporarily blocked from proceeding by the Supreme Court on Oct. 18. The Department of Justice contends that letting the case proceed would be too burdensome, unconstitutionally pit the courts against the executive branch, and require improper “agency decision-making” by forcing officials to answer questions about climate change. The Justice Department also argues there is no right to “a climate system capable of sustaining human life.” The Supreme Court said it would rule on whether the case could proceed in the lower court after it received responses from the plaintiffs and the lower court to the Department of Justice's objections.

I’m 66 years old, so can’t expect at most more than 2 or 3 more decades on this planet (and with my family health history, less than 1!). But I have children. It’s my job as an adult to be one of those helpers, trying my best to make disasters less likely in the future. Some of us have expertise and life experiences that qualify us to focus on specific issues, but all of us American citizens are human beings who were given a system that at least aspires to “liberty and justice for all,” and a government whose stated aim is to “form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity.” Our system and government have always fallen short of these well articulated ideals, but it’s our job as adults to roll up our sleeves and make that system and government better.

Captain Sully Sullenberger, who like Mr. Rogers was a lifelong Republican, became famous for that “Miracle on the Hudson.” He wrote in today’s Washington Post:

As captain, I ultimately was responsible for everything that happened. Had even one person not survived, I would have considered it a tragic failure that I would have felt deeply for the rest of my life. To navigate complex challenges, all leaders must take responsibility and have a moral compass grounded in competence, integrity and concern for the greater good.

I am often told how calm I sounded speaking to passengers, crew and air traffic control during the emergency. In every situation, but especially challenging ones, a leader sets the tone and must create an environment in which all can do their best. You get what you project. Whether it is calm and confidence — or fear, anger and hatred — people will respond in kind. Courage can be contagious.

Today, tragically, too many people in power are projecting the worst. Many are cowardly, complicit enablers, acting against the interests of the United States, our allies and democracy; encouraging extremists at home and emboldening our adversaries abroad; and threatening the livability of our planet. Many do not respect the offices they hold; they lack — or disregard — a basic knowledge of history, science and leadership; and they act impulsively, worsening a toxic political environment.

As a result, we are in a struggle for who and what we are as a people. We have lost what in the military we call unit cohesion. The fabric of our nation is under attack, while shame — a timeless beacon of right and wrong — seems dead.We need to be stepping up to the plate to restore American values—the ones that safeguard our air and water, an essential part of that “general welfare” our Constitution calls for, and that safeguard every one of our citizens against ugly, genuinely evil forces that would divide us, when our government’s existence was created to form a more perfect union, establish justice, and insure domestic tranquility.

As the children in the lawsuit know, and as an army of legitimate scientists have told us, the changes in climate endanger everyone in America as well as throughout the world. My precious daughter lives in New York, a coastal city, and my precious son Joey in Florida—it’s my job to be a helper protecting them as much as possible at this late date from the effects of climate change and the horrifying rampages of white supremacists.

We are facing a big choice next week, one that will decide whether the leaders we follow are like Captain Sullenberger and Fred Rogers, or ones that will keep leading us down this dark tunnel. As Sullenberger concluded in today’s op-ed:

Our ideals, shared facts and common humanity are what bind us together as a nation and a people. Not one of these values is a political issue, but the lack of them is.

This current absence of civic virtues is not normal, and we must not allow it to become normal. We must rededicate ourselves to the ideals, values and norms that unite us and upon which our democracy depends… We cannot wait for someone to save us. We must do it ourselves. This Election Day is a crucial opportunity to again demonstrate the best in each of us by doing our duty and voting for leaders who are committed to the values that will unite and protect us. Years from now, when our grandchildren learn about this critical time in our nation’s history, they may ask if we got involved, if we made our voices heard. I know what my answer will be. I hope yours will be “yes.”