April 20, 2020, was the 10-year anniversary of the explosion of the Deepwater Horizon oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico. I had left my dream job at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology just two weeks before—my 91-year-old mother-in-law was having difficulties living alone in the woods in northern Wisconsin and I was finding it increasingly hard to be away from Russ so much. I wanted to hunker down at home for a while, but the oil spill was so huge, with accurate information about its impact on birds so scarce, that Russ and I decided it would be worth it for me to drive down to Louisiana and Alabama for a few weeks in July and August to get a closer look. Going down there and seeing first-hand what was happening was and remains the single most disillusioning experience of my life.

As I set out on my drive on July 24, even as the news was filled with the continuing gushing oil, the official stance was that the Corexit dispersant BP was spewing over the Gulf was taking care of the most of the oil, and the hot temperatures in the Gulf were making the rest evaporate. This was clearly and obviously magical thinking, like imagining the oil was being Raptured up for all eternity.

Those of us who followed oil spills in the past knew how bad this one would be as millions of gallons of oil kept gushing, day after day after day—the well wasn’t sealed until September 19, five months after the original explosion, with 134–210 million gallons of oil released into the Gulf.

|

Oil on the natural beach at Grand Isle State Park on July 29. This part of the beach wasn't public,

so it wasn't cleaned. Who would know or care? |

The official total of oiled birds was amazingly low—it still stands at an unbelievable 63,000–100,000 birds even as knowledgeable scientists say the real number had to be one or even two orders of magnitude greater than that. As the first numbers came in, I was seriously wondering how they could possibly be accurate. April is the peak of spring migration through the Gulf as well as the start of the local nesting season. Simple common sense said the numbers should be way, way bigger from an oil spill of that magnitude in that unique location.

|

| Drew Wheelan |

On top of my own misgivings, the American Birding Association’s Drew Wheelan was finding evidence that dead birds were being disposed of without being counted, and that many badly oiled birds still clinging to life weren't counted either. Even though Drew was way more credible than the people saying the oil wasn’t a problem, I wanted to see for myself.

When the explosion happened, and as oil started reaching bird nesting islands along the coastline, biologists, photographers, and videographers from Audubon, the Cornell Lab, American Bird Conservancy, and National Geographic were already on the scene, right there on the ground, some specifically studying and documenting nesting colonies that became doomed. They took a lot of photos and videos both before and after the oil reached them, producing horrifying confirmation of how devastating the oil was for nestling and parent birds. Drew recently told me, "At the time, the American Bird Conservancy was really doing all they could to try and influence whoever they could to put pressure on the powers that be to do the right thing."

But BP and the U.S. government insisted on a 5-year moratorium on the publication of ANY studies or videos or photos regarding the impacts on wildlife. They obviously couldn’t silence the news media, Drew Wheelan, nor unaffiliated individuals like me, but could exert plenty of pressure on organizations that depend on cooperative agreements and grants from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other federal agencies to do essential work.

The rationale for the 5-year delay was ostensibly because this information would somehow damage the federal government’s legal case against BP, but BP significantly benefited from keeping the American people and politicians in the dark about the horror. And seriously, how could transparent fact-finding regarding the impact on wildlife have harmed the case against BP?

Disillusionment

When I reached the Gulf, I realized that the oil spill was a horror fully as bad as I expected, and I felt enraged that the corporation was getting away with making it appear much less significant that it was.

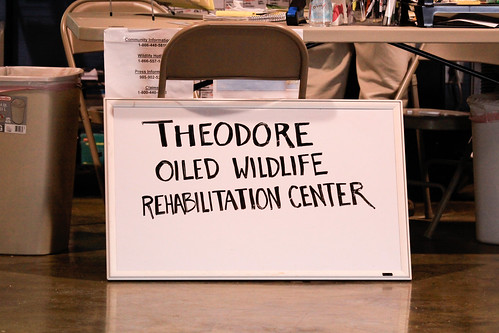

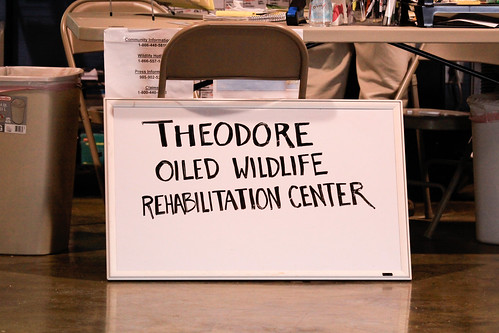

The International Bird Rescue Research Center was selected to do the rehab work, and I got to see their work at the Theodore Oiled Wildlife Rehabilitation Center. They did a great job of treating the oiled wildlife they were brought, but they were prohibited from actually collecting oiled birds themselves. Absolutely NO professional rehabbers trained in recovering oiled birds were sent to the Gulf or allowed to go there on their own to recover wildlife. Several licensed, professional wildlife rehabbers with specific training in retrieving and rehabbing oiled birds told me that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had told them they'd lose their rehab license if they went to the Gulf.

I saw quite a few oiled birds, including one drenched Black-crowned Night-Heron standing on an oiled boom near the shore of Cat Island when I was on a boat trip.

Our boat captain agreed to approach the boom to try to net the heron to bring for rehab, and we'd have succeeded except that as the boat got near, the poor bird opened its wings. It was too badly oiled to take off, dropping into the shallow water and awkwardly waddling and thrashing to shore, but the fact that it had opened its wings at all meant that it was "flighted" by BP's definition. The captain told us he could lose his license if he tried to capture a flighted bird.

Why were the rules so ridiculously and cruelly stringent? I couldn't wrap my head around it until I realized that the only birds being included on the official count, which would determine BP's liability, were ones that were physically retrieved, dead or alive, and this rule about "flighted" birds lowered the numbers even more. In previous oil spills, the count always included field observations by qualified birders, biologists, and other knowledgeable people. BP managed to sneak these rule changes in under the radar of almost everyone. This drenched and doomed heron did not meet the new criteria for oiled wildlife and would never be counted.

The September-October 2010 issue of Audubon came out a few weeks after I returned home, while oil was still spewing, with the cover story about the spill. (They've pulled that article off their website now, but I quote extensively from it on this blog post from back then.) The article seemed to be about an entirely different oil spill than the one I had just seen and smelled with my own eyes and nose. The article attacked Drew Wheelan by name so strongly, unfairly, and personally that I quit the organization. That’s also when I renewed my lapsed membership in the American Birding Association.

The article promoted BP’s absurdly false claim that this oil was unique:

Deepwater Horizon oil is different. It is highly volatile, and nearly half evaporates immediately. In the intense heat, bacteria consume other fractions. Also, the leak is almost 50 miles at sea, giving dispersion and natural breakdown processes more time to kick in.

The surface water in the Gulf, especially near shore, is indeed quite warm, but temperatures at the depths of the well are much colder than at the surface, and I personally saw plenty of oil that had reached shore. The article also claimed that the low-tech booms encircling most of the islands were protecting them from oil. "Finally, much has been learned about boom laying and skimming, and operations are massive and intense." But much of that boom hadn't been anchored in place and washed ashore with the oil.

Drew Wheelan tried to drum up public concern about the oiled nesting colonies, but the environmental organizations that were getting photographs of them (some of those photos are in Cornell's current article, "Ten Years Later," in Living Bird), stayed distressingly quiet about it at the time. One Cornell staffer commented on my blog post about the 2010 Audubon cover story, “I respect Drew Wheelan's commitment to write about this disaster, but he has mainly served as a voice of outrage rather than as a source of information.” This seemed ironic because Cornell was one of the organizations sitting on photos, videos, and other information that could have confirmed everything Drew was saying. Information was hard to come by after virtually all of the oiled islands and coast were closed off, ostensibly for public safety.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service continued to prohibit anyone from rescuing oiled birds in the nesting colonies, even after 100 percent of the nestlings on some islands had been oiled, claiming nesting could be "disrupted." In other years, they’ve allowed banders to capture birds in those colonies, and that very year they'd allowed organizations to send people onto the islands to get photographs and video.

It was vastly in BP’s interest to minimize the number of birds captured for rehab. Audubon was responsible for coordinating volunteers, and bears some responsibility for keeping licensed, professional rehabbers from helping save birds’s lives and more fully documenting the number of oiled birds. Perhaps Audubon's staffers were unaware of how much this helped BP limit its liability. The cover story quoted Audubon’s Melanie Driscoll:

"If we do nothing, they could die,” said Driscoll. “They’re at risk of overheating and sunburn, hypothermia if they get wet. But if we evacuate them, they won’t be taught to fend for themselves, and they’ll probably die, too. The thought is that now that they’re close to molting they’ll drop their oiled feathers and a few will make it. I don’t know if that’s a good theory, but we’re in a situation where there’s no good decision. The best decision is not to have an oil spill.”

Rehabbers keep developing better techniques for helping injured, orphaned, and oiled birds learn to "fend for themselves" to survive in the wild. It's absurd to think that giving them at least a chance in this case was a worse option than leaving them to die coated in oil. And there were several oiled colonies. If it was truly an issue of not knowing whether recovering and rehabbing them or leaving them was better, why couldn’t they have rehabbed at least one colony to get comparison data? Leaving every one of them out there to die horrible deaths was better for BP's bottom line.

When Does Pragmatism Become Complicity?

When I became a birder in 1975, Russ and I were both students living on part-time jobs and graduate assistantships with virtually no discretionary income, yet I immediately joined Michigan Audubon, Lansing’s Capital Area Audubon Society, and National Audubon. I learned a lot about birds from the local and state groups, and a lot about protecting birds from all three. And the day I identified the very first bird on my lifelist, that Black-capped Chickadee I talk about endlessly, I became a major fan of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology—their recording of bird vocalizations at the Michigan State University library clinched my very first bird identification. I joined the American Bird Conservancy as soon as it started in 1995. I continue to support these important organizations today, though I did take a hiatus from Audubon after they published that cover story about the BP spill.

None of these organizations were explicitly colluding with BP, but they sure were helping BP by keeping silent about just how bad the oil spill and the response to it were and by never acknowledging the enormous change in how the official count of oiled birds was made, much less how by keeping the numbers so low BP was minimizing its legal liability. (Again, though, Drew Wheelan said he knew at the time that the American Bird Conservancy was doing what they could.) Audubon and Cornell never challenged the attacks on bird rehabilitation suddenly popping up in the media, conveniently for BP, claiming that rehabbing birds is a waste of conservation dollars and that rehabbed birds are essentially doomed anyway. Ironically, one of the photos in Cornell's current Living Bird is of a healthy banded Brown Pelican photographed in 2020, a bird that had been rescued and rehabbed during the BP spill.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service made things much worse by threatening to rescind rehab licenses from any rehabbers who turned up in the Gulf to help retrieve oiled wildlife. Audubon’s cover story ridiculed the very idea of capturing oiled birds, writing about a television interview Drew Wheelan did:

He and Anderson Cooper spoke of “experts” who supposedly possess the power to pluck birds from the firmament, a feat impossible for any human save Harry Potter.

I’m still gobsmacked about that tripe. It's as if the writer had never observed a bird banding operation or ever gone out with bird rescuers after other oil spills. The Cornell staffer's comment on my blogpost included this:

It's easy to say that rehabbers ‘know how to catch birds’ and quite another thing to have them do it from a barren stretch of oiled sand with a thousand invisible nests underfoot, or from within the oiled tangles of a mangrove rookery.

But the biologists documenting those nesting colonies, including the ones who took the photos in the current Living Bird article, were working right there along that “barren stretch of oiled sand” at the time. And rehabbers who specialize in retrieving oiled birds have worked on other coastal island spills during nesting season. Of course it wasn't possible to save every oiled bird, but a great many could have been saved if only it didn't impact that all-important total count that set BP's liability.

I went to the Gulf as an unaffiliated individual, paying my own way for everything, subsidized by no one except my husband, my treasured friend Kathy Hermes who supplied me with a bazillion quarters for parking and vending machines, and the KUMD radio station in Duluth, which didn't provide any financial support but gave me a press pass in case I needed it. I posted my accounts, with photos and video, on my personal blog, and produced a few “For the Birds” programs on the road during the trip.

I did my level best to verify and document everything I wrote and to be fair. And I did my best to control my Irish temper. But I was about as smalltime a reporter as one could be. My work hardly went viral, but Anderson Cooper’s fact checkers from CNN came across it and called and emailed a few questions.

Smalltime or not, my work caught the attention of a few conservation big guns. I received one anonymous email from a hotmail account reminding me that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had the power to rescind my permit to keep my education owl, Archimedes, if I wasn't "careful." I had worked as science editor at Cornell for over two years, and apparently that connection was well-enough known that I got a couple of phone calls from the Lab asking me to tone down my posts about the spill. I said I’d be more than happy to correct any and every error, but I was not representing myself as anything but the unaffiliated individual I was, and nothing I’d written was untrue.

The current Living Bird article discusses how various conservation groups and state agencies are using their share of the $20.8 billon that BP paid to settle all civil and criminal claims. Some are restoring islands in the Gulf that are once again hosting plenty of nesting birds, though those restoration projects are also intended to benefit property owners and corporations on shore, serving as buffers in storms and as water levels rise. Meanwhile, some other islands have been lost completely—plant root systems are what form and hold these islands in place, and when they are killed, the island disappears. And other islands, not a high enough priority for the people working with limited settlement money, are still in horrible condition.

The Minnesota DNR, in part funded by settlement money, is studying how badly our own loon population, which mostly winters in the Gulf, was impacted by the spill. It’s a heck of a lot of money for even the largest non-profits, and the government agencies, universities, and organizations doing these studies and this restoration work badly need these funds to accomplish their important work. That is the simple truth, and it’s why I continue my support of Cornell, and after a few years renewed my membership in Audubon.

But somehow, I can’t forget that $20.8 billion isn’t even a tenth of BP’s income of $278.4 billion from 2019 alone, and more like 1 percent of their total revenue in the decade since the spill, nor can I forget that $20.8 billion is nowhere near enough to restore all the islands damaged by the spill. Aren't penalties supposed to serve as a deterrent to prevent future wrongdoing, not just a minor expense of doing business?

I cannot forget how long BP fought against even this insufficient settlement and then how long it took them to pay out any of the funds. And I cannot forget how they minimized that final amount by insisting that the official bird kill total, which determined their liability, would include, for the first time ever, only birds physically retrieved rather than counted in the field by qualified experts. And exacerbating that, they even managed to limit which badly oiled birds could be rescued, dooming thousands that could have been saved.

"Ten Years Later" in the current Living Bird is an important article, published by an important ornithological organization, but it must not be the final word. Environmentalists and bird conservationists need to reckon with how we weigh honesty, transparency, and trust vs. quietly allowing companies responsible for disasters to call the shots, "going along to get along." The organizations and agencies partaking of that $20.8 billion settlement are indeed doing valuable work with it, but much more valuable work should have and could have been done, if only all the witnesses from all the organizations and agencies had spoken out in concert, loudly, clearly, and truthfully. Then the final settlement almost certainly would have been set to mitigate a more accurate total number of oiled wildlife, more fairly reflecting the magnitude of the damage.

Non-profits sitting on their own data about the spill for five years, especially as they discredited and squelched the forthright testimony of truthful witnesses while the spill was happening and birds were dying, left a stain that won't wash away. We environmentalists, both as individuals and as organizations, must thoroughly examine the mistakes that were made in 2010 so the next time there's a huge oil spill, and there will be a next one, we may do better.