When I started birding in the 1970s, the scientific consensus was that virtually all bird song is performed by males. Yes, there were a few exceptions, especially among some tropical birds in which pairs perform amazingly coordinated duets, but the rule that males were the main singers stood.

In recent years, more and more studies have revealed that a great many more female birds sing than was ever appreciated. The landmark 2014 study by Karan Odom found that females sing in 71 percent of the surveyed species of 32 families. Her extensive research also established firmly that both sexes almost certainly sang in the common ancestor of all bird species--a radical idea in ornithology. As I read more and more of these new papers about female birds singing, I couldn’t help but notice that not only Karan Odom’s Ph.D. research but also most of the other work has been primarily authored by women.

That observation turned out to be accurate. On August 26, the University of Maryland Baltimore County, where several of these scientists are centered, released a study in Nature Communication revealing that women make up only 44 percent of the first authors on general birdsong papers but 68 percent of the first authors of papers about female birds singing. Without this seminal work, we’d still be following the old, false line of thought that mainly male birds sing.

On the very day that I read about this, I was reading a 1953 paper in The Canadian Field-Naturalist, “Nesting Life and Behavior of the Red-eyed Vireo,” by Louise de Kiriline Lawrence. Red-eyed Vireos happen to be one of the species in which it really is just the males singing, but that’s not why I was looking up the species. I’d been seeing a couple of family groups of Red-eyed Vireos in my yard after not noticing any nests in the close vicinity. I wondered how long the families stay together, and whether this wandering away from the nest site marks the start of their migration. I also wondered whether family units tend to stay together for part of or even all of their fall journey, or whether some of the young stick with the mother, or the father, as the adults go their separate ways. The Red-eyed Vireo entry in Cornell's Birds of the World, written by three male researchers, said this in the section about fledglings associating with their parents:

Little information. Young typically move far from nest site and are difficult to relocate; 3 d after young leave nest, most researchers cannot find adults or young. Lawrence, however, reported following family group for 31 d after young left nest. These young were fed regularly by at least 1 parent for first 15–16 d. Until day 25, they were fed only occasionally, despite frequent begging.

So I looked up Lawrence's paper. Louise de Kiriline Lawrence was a prolific field researcher who, over her career, wrote more than 500 reviews and 17 scientific papers for the American Ornithologists’ Union and 7 books, and was Audubon’s most prolific writer. She also banded 25,000 birds. Her Red-eyed Vireo nesting paper was based on following 9 particular pairs, but she did not band many of those individuals. She wrote:

Since I felt it was more important to observe birds act with as little interference as possible, no banding was attempted at the nests with the exception of some nestlings. Only one adult male was caught by accident and banded. For the recognition of individuals and pairs especially in 1949 and 1950, I relied therefore on the careful, almost daily, search of the territories, census, and the studying of individual traits in song, plumage, or behavior.

Lawrence, born and raised in Sweden, was the daughter of a naturalist/conservationist. She served as a Red Cross nurse stationed in Denmark during World War I, fell in love with and married a Russian officer, and then was captured with him by the Russian revolutionaries. He was killed and she escaped and settled in Canada as a public health nurse in the northern wilderness, where she became the nurse for the world’s first surviving set of quintuplets, the famous Dionne Quintuplets.

Dealing with newborn quints may have been excellent preparation for keeping track of active, virtually identical individual vireos. Regardless of how she came by her skills, she’s been one of the only researchers ever to successfully follow Red-eyed Vireo families for three days, much less a full month, after the young fledged. But she didn’t track them on migration, there not being the kind of tracking technology during her lifetime that there is now. So the answers to my questions about my backyard vireos will go unanswered for now.

But in reading Lawrence’s paper, I saw that not only had she been the only ornithologist to successfully track vireo families; she had also made an important discovery that disproved what prominent ornithologists had always believed—that male Red-eyed Vireos as well as females incubate the eggs. In her paper, she cited what these authorities had written, and then noted:

As I began this study, however, I soon found that this information was not in agreement with my observations, a circumstance which obviously required an especially careful investigation. On the basis thereof, I present my evidence that in the Pimisi Bay region the female Red-eyed Vireo was always found to incubate alone with no assistance from the male.

After making her case based on the individuals she tracked, she also noted:

[Margaret Morse] Nice found the female Red-eyed Vireo alone incubating at a nest in Jackson Park [in Chicago], and in 1949 she wrote to me: “I’ve never known of a dependable instance of the male Red-eye incubating…” Kathryn Ann Graves said in the abstract of a paper which she was to have given at the 67th Stated Meeting of the A.O.U., October 1949: “My conclusion that incubation is performed by the female Red-eyed Vireo alone is based on three lines of evidence: 1) the behavior patterns of the adult birds at six nests during the incubation period; 2) observations of a pair the sexes of which could be distinguished with absolute certainty owing to the distinct marking of the female’s feathers with black indelible ink; 3) analysis of the incubation rhythms of the females on four nests, and a comparison of these rhythms with those of 23 other passerine birds.”

It seems significant if odd that the discovery that only female Red-eyed Vireos incubate the eggs, and the more recent discovery that so very many female birds sing, were made by women. Is it that my sex is more likely to keep an open mind about female sex roles and division of labor in bird pairs? Or was there another reason why the vast majority of ornithologists, most of them male, clung unquestioningly to the conventional wisdom about the greater importance of male birds for so long?

Margaret Morse Nice, who had also noted that only the female Red-eyed Vireo incubates, was the author of most of the seminal work on the Song Sparrow. She of course conducted a major literature search to find out what was already known about the bird she would study for decades. She found the details reported for Song Sparrows “meager enough information and all of it wrong.” The literature was so rife with errors regarding easily verifiable details, such as clutch size and incubation times, that she started looking into the accuracy of that kind of information in other species. Apparently many species accounts weren’t based on any actual firsthand observations of the birds. For example, she discovered that the reported but inaccurate incubation times for American birds had been carried forward from author to author over the decades without anyone bothering to actually find and keep track of a few nests to verify. When she tracked down the original source, she found that he’d never observed the incubation times of birds he was reporting on himself, but had simply inferred them from observations and speculations of the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle!

A year or two ago I was leading a field trip on Hog Island in Maine. My co-leader was a prominent ornithologist whom I genuinely like a lot and don't consider particularly sexist, but I was gobsmacked when we came upon a singing Red-eyed Vireo and I mentioned that a Red-eye had once been followed for a full day as it sang 22,197 songs. He laughed and said that the woman who counted those songs clearly had “too much time on her hands.”

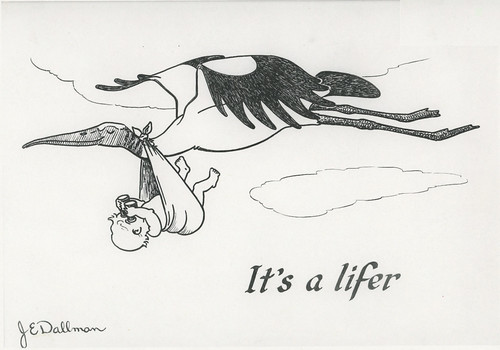

But that woman was hardly the stereotypical bored housewife of his imagination; she was Louise de Keriline Lawrence herself. When acclaimed British ornithologist Noble Rollin suggested people devote a whole day to one special bird activity, she accepted the challenge by following one Red-eyed Vireo from 3 am through his heading to roost before sunset. She didn’t just keep a running tally of the bird’s songs as she followed him throughout his 3-acre territory; she kept track of his behaviors, minute by minute and hour by hour, and noted what else was happening, as well. The article she wrote about that day is rich and lyrical, transcending simple enumeration to give us a lovely portrait of one bird, all because she was a meticulous, clear-eyed scientist with more substantial work to her credit than any ornithologist I know today. She wrote an article for Audubon in 1954 about that memorable day, “Voluble Singer of the Tree-Tops,” which is well worth reading in its entirety. (I can't find an online copy of the article and it's probably still copyrighted, but it was included in her 1980 book, To Whom the Wilderness Speaks (available on Kindle) and also appeared in the 1999 book, Bright Stars, Dark Trees, Clear Water: Nature Writings from North of the Border, edited by Wayne Grady.)

Too much time on her hands? No. Louise de Kiriline Lawrence was doing the painstaking and meticulous but richly satisfying work of an excellent field ornithologist. The days of ornithological societies excluding women are over, but apparently not the days of dismissing solid research done by women. This is why diversity and inclusiveness in any field is so important. Eyes looking at questions from different angles help find the actual truth.