From my very earliest memories I’ve loved birds. This is connected with my grandmother, whose name was also Laura. She died when I was very little but I remember her, and family lore has it that she loved birds. When my Grandpa gave me The Little Golden Activity Book: Bird Stamps, he told me it was because my Grandma had loved birds just like me.

My Grandpa always kept two canaries in his dining room, but I don't associate him with birds the way I do my Grandma. No, the love he inspired in me was for the Chicago Cubs. He never missed listening to or watching a game on TV unless he was at Wrigley Field seeing it live. When we watched games on Channel 9, he’d tell me about the game itself, but also about the players. He particularly liked Ernie Banks, so of course I did, too. Ernie Banks, the Chicago Cubs, and my Grandpa are inextricably intertwined in my brain and heart. Banks started playing for the Cubs in 1953 while I was still one year old and stayed with the team for the rest of my childhood and my Grandpa’s life. My Grandpa died in 1970, and Ernie Banks retired in 1971, every one of his 19 seasons in the Major Leagues with the Cubs. For a few memorable years, Ernie Banks was my friend on Facebook. Russ gave me a baseball autographed by him for my 70th birthday last year.

Somehow it was always easy to love Ernie Banks and the Cubs even though I never particularly followed a baseball season from start to finish until 2016. I had no idea how well the Cubs were doing—the reason I picked 2016 was simply that January 11 marked my Grandpa’s 120th birthday, so I decided that in his honor, and in honor of Ernie Banks, who had died the year before, I’d get a baseball app and pay attention to every single Cubs game for the entire season. The only week I couldn’t pay attention was in October when I was birding in Cuba, where news from the US was blocked.

I really was planning to follow the Cubs just that one season, but over the course of it, I grew to care about the players. And in the same way that my enjoyment of the games of my childhood centered around first baseman Ernie Banks, I focused in 2016 on first baseman Anthony Rizzo. That year I had a couple of other favorites, too, but the one I’ve followed diligently every year since then, becoming increasingly fond of, is Rizzo. When he comes up to bat, I find myself singing in Maria’s voice, from West Side Story, “Tony, Tony, Tony.” The night the Cubs won the World Series, with an infield grounder fielded by Bryant to Rizzo to make that final out, I was so thrilled that I couldn’t settle down until 1 am. When I took my little dog Pip out before finally heading to bed, a Boreal Owl was calling in my backyard! Clearly, I wasn’t the only one celebrating.

In 2008, while he was still in the minor leagues, Anthony Rizzo had Hodgkin’s lymphoma, the horrible disease that killed one of my cousins back in the 1970s. Fortunately, treatment has improved enormously since then, and Rizzo made a complete recovery. He and his foundation have been tireless advocates for families dealing with cancer and for cancer research. Rizzo grew up in Parkland, Florida, and attended Marjorie Stoneman Douglas High School. After the horrifying school shooting in 2018, he attended vigils for the victims and helped raise large amounts of money for victims, their families, and the school. Rizzo is well known to be an excellent role model for rookies and an essential glue binding his team together. And I loved how in most of his Cubs games, he used eye black, which helps reduce glare in the exact same way that many birds have dark markings below their eyes to reduce reflections in bright light.

|

| A Laughing Falcon with nature's own eye black |

|

| Anthony Rizzo with eye black |

But perhaps the most compelling reason I singled in on Rizzo from the start is that he looks a bit like my son Joe, who lives in Florida where Rizzo came from.

Ernie Banks was always a Cub, from the start of his career in the Major Leagues until the end, so I never had to work out which was more important to me—the team itself or my favorite individual player. Last year I had to figure that out the hard way, when the Cubs traded Rizzo to the New York Yankees. Suddenly, I find myself following every single Yankees game as well as every Cubs game.

Rizzo, a left-handed slugger, has always hugged the plate, a time-honored strategy for hitting that put him on the All-Star team three times and made him an MVP almost 50 times so far during his career. He’s hit 32 home runs this year, placing him in 12th place in the major leagues this season, at least as of today. But his strategy for hitting also places him in jeopardy for getting hit by pitches. He’s not crazy—he stays in the batter’s box, never crossing into the strike zone where the pitchers are ostensibly aiming. He’s not trying to get hit, but he is fearless, knowing he has a better chance of making a solid connection where he stands than a little further from the plate. So his slugging record comes at the expense of getting hit by pitches more than most players. Indeed, in three of the seasons he’s played, he’s led the major leagues in the number of times he’s been hit by a pitch.

On Thursday night, while I was at Hawk Ridge Bird Observatory's 50th anniversary banquet, I had to track the Yankees-Red Sox game on my friend Erik Bruhnke’s phone because I’d forgotten mine. And that night, Rizzo got hit by a pitch for the 19th time this season. (Well, actually, the 20th. On August 15, he got hit hard on his thigh but umpire DJ Reyburn claimed he’d leaned into it. I was listening to the game and watched replays, and the pitch was behind Rizzo, way, way out of the strike zone—where was Rizzo supposed to go?! But the umpire'a ridiculous claim was a non-reviewable call.) The hit-by-pitch Thursday was the 197th official one in Rizzo’s career—the one I’d been looking forward to for a long time, because it placed Rizzo in 10th place in the all-time Major League Baseball standings for hits-by-pitches, tying with Minnie Minoso (if you count the times Minoso was hit by pitches in the Negro leagues, which of course belong in the stats). Then, on Monday the 26th, he got hit again, so with 198 hit-by-pitches, Anthony Rizzo is now tied with Frank Robinson for 9th place.

Being hit by any pitch is dangerous as well as painful. In 1920, Ray Chapman, playing for Cleveland, was hit in the head by a ball thrown by Yankee pitcher Carl Mays. Blood gushed out of his ear and he died 12 hours later. That led to a rule change that pitchers could no longer throw spitballs or coat baseballs with dirt, licorice, tobacco, tar, or other substances that made the ball go more erratically and also made it harder for the batter to see. You’d think it would also have led to a rule requiring batters to wear protective helmets at the plate, but that didn’t come about until more than 30 years, and a lot more injuries, later.

In 1936, while playing for the Negro leagues, Willie Wells got hit by a pitch that knocked him unconscious. He insisted on playing the next day, this time wearing a helmet lined with cork. The next year, Mickey Cochrane’s career with the Detroit Tigers ended when he suffered a near-fatal skull fracture on a pitch by Yankees' Bump Hadley. Finally there was a strong call for batter helmets, but players and most teams resisted. Batters said they couldn’t see the ball as well wearing a helmet, and the issue wasn’t settled through the 30s or 40s. In 1954, Joe Adcock, a first baseman for the Milwaukee Braves, was struck by a pitch on his head while wearing a helmet. Taken off the field on a stretcher, he was uninjured; his helmet was visibly dented. (This reminds me of when a car in the right lane made a left turn right into my son Joe on his motorcycle. Joe's arm was broken in seven places and the rest of his body battered, but his head was fine. His helmet? Not so much.)

First the National and then the American Leagues started recommending helmets and making them sort of mandatory, but it wasn’t until December 1970 that MLB set a strictly enforced helmet mandate. Even then, older players who didn’t want to wear one were allowed to play without it. The last Major League player to bat helmetless was the Red Sox’s Bob Montgomery in 1979, a time well within my memory but before any active players of today had been born.

Hit-by-pitch injuries on two of my other favorite Cubs—Ron Santo getting his cheek fractured in 1966 and Jason Heyward getting a broken jaw in 2013—explain why protective ear flaps and then the C-flap were developed, to protect more of the head and face. Rizzo of course wears protection when batting. Indeed, the Rizzo bobblehead on my desk near my signed Ernie Banks baseball depicts Rizzo wearing his Yankees batter’s helmet.

Batters are not the only ones who can be hit by a pitch. Among human beings, catchers and umpires are also in the line of fire. But oddly enough, non-humans are also at risk. On March 24, 2001, during a spring training game, Diamondback pitcher Randy Johnson threw a 100-103 mph ball that made it about ¾ of the way to the plate when suddenly the ball disappeared in an explosion of feathers—somehow a hapless bird had flown by at precisely the wrong moment. The umpire, catcher, and batter were stunned. When they figured out what happened, it was ruled a no pitch because there is no official rule that covers that bizarre scenario.

Ornithologists interviewed by Newsweek at the time said the bird was most likely a Mourning Dove, but I am at least somewhat skeptical because I can’t find evidence that the carcass was retrieved to be accurately identified. One of the articles about it uses a photo of a Eurasian Collared-Dove to illustrate the Mourning Dove, which tells you how important ornithological accuracy is in the sporting world.

|

| Mourning Dove |

|

| Eurasian Collared-Dove. There is a difference! |

That same year, Johnson was named co-MVP of the World Series when the Diamondbacks beat the Yankees, but to this day, he says that people ask him more about hitting the dove than they do about his critical role in Arizona’s first World Series win ever or anything else in his storied career.

After retiring from baseball, be started a photography business. The exquisite wildlife photos on Randy Johnson's website provide solid proof that he cares about wildlife conservation. His photos run heavily to mammals, with stunning pictures of elephants, lions, leopards, and gorillas. There’s one gorgeous shot of a Blue-footed Booby, but the only other bird currently depicted on his website is within his logo: a songbird lying flat on its back with feathers flying. The astronomical improbability of hitting a flying bird with a pitch juxtaposes genuine tragedy with slapstick humor.

It was obvious at the time that Johnson felt bad about it, but his webpage makes it clear that he’s mustered a sense of humor about how that single unforeseen and freakish moment has overshadowed his long Hall of Fame career.

The only other time in baseball history that a pitcher hit a bird, as far as I can find, is from 2014, in a Class A minor league game when John Maciel hit a bird that wasn’t identified. Someone calculated that in the Major Leagues, almost 6.5 million pitches were thrown just between 2008 and 2016, and during that time frame, zero of them, and zero pitches in the millions thrown since, has hit a bird.

Those two bizarre incidents were accidents. But in 1983, Yankees outfielder Dave Winfield killed a gull—I’d guess a Ring-bill—in Toronto with a warmup throw. It sounds like the bird was sitting, not flying, and the throw appears to have been intentional. The Ontario police charged him with animal cruelty, although that was later dropped.

All in all, I’m very glad that Anthony Rizzo is sturdier than a bird.

Rizzo must have noticed birds during his childhood, and one would hope that his education at the high school named for one of the most important environmental writers in Florida’s history included information about some of Florida’s bird life. I don’t know if he ever noticed a Peregrine Falcon flying over Wrigley Field as I once did, or if he ever walked past the Picasso at Chicago’s Civic Center when clouds of pigeons took off, or if he’s ever taken a stroll through Green Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn and noticed the Monk Parakeets. I know if I were a baseball player, I’d spend at least part of my down time on road trips checking out the local bird life, but I doubt that real professional baseball players have much time to notice birds except in the event of a freak accident.

So far, I don’t think any baseball announcers or news reporters have noticed that Rizzo just made it to the all-time Top Ten in MLB history for being hit by pitches, and I've never heard anyone ask him about the birds in his life. But it sure would be fun to know what my favorite baseball player’s favorite bird is.

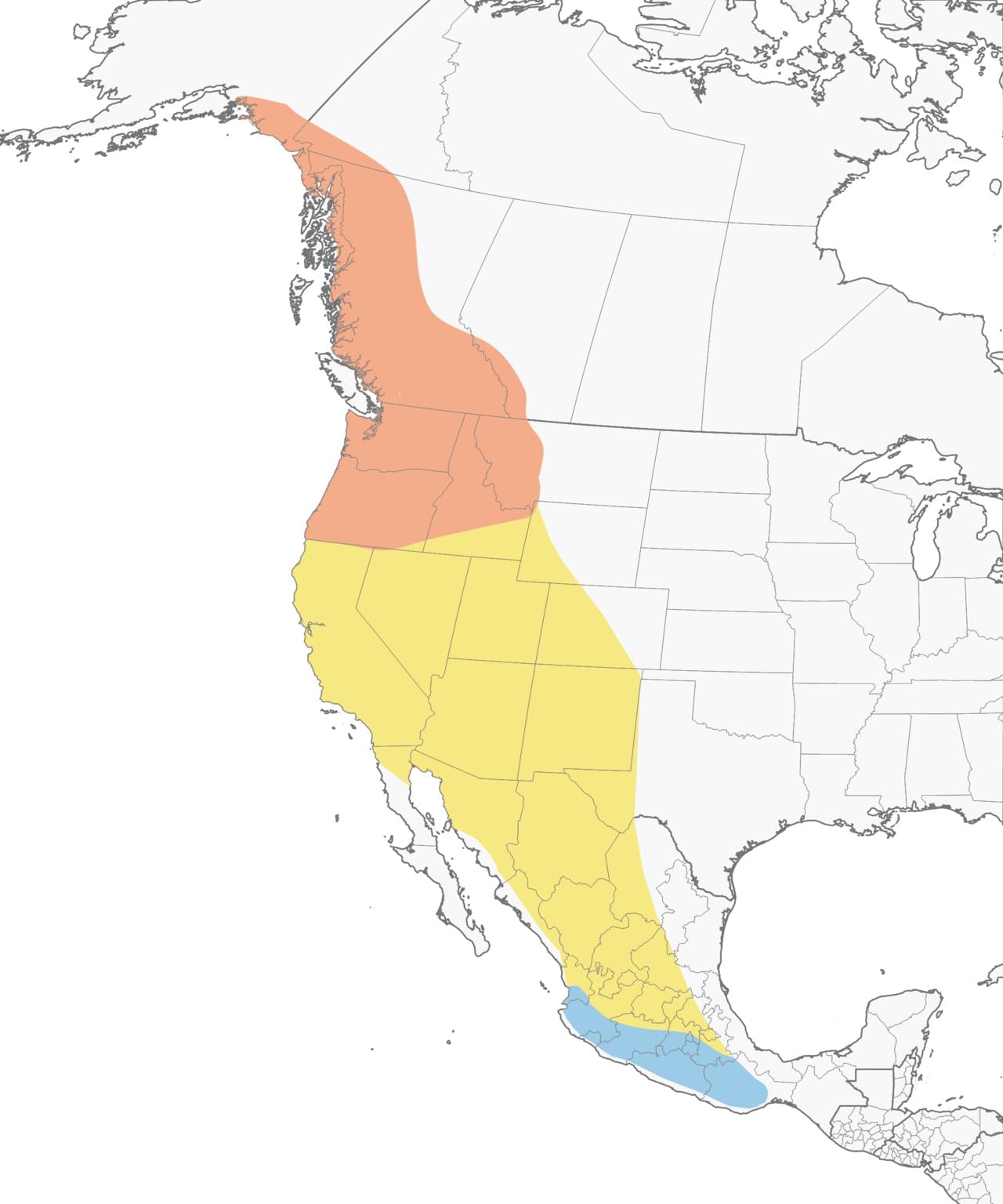

|

| My favorite ball player with my favorite bird |

Addendum: On Tuesday, September 27 (the day this was published), Rizzo got hit by yet another pitch! Now he holds 9th place alone, with 199 career hit-by-pitches.

Addendum: On Wednesday, September 28, Rizzo was the Yankees' acting manager when Aaron Judge hit his 61st home run of the season. I love that!

Addendum: On Saturday, October 1, Rizzo got hit by a pitch yet again. #200!!!!! Four to go and he'll tie Chase Utley for 8th place. Plus, as Suzyn Waldman (my favorite baseball announcer of all time) pointed on out WFAN Saturday, he's one of only FOUR players ever to have at least 200 homers and 200 hit-by-pitches in their career!!!