Wednesday, January 31, 2018

The Minnesota Vikings' Curse of the Bird-Killing Glass

On Sunday, the Super Bowl will take place in a tragically flawed new stadium, much of it constructed of bird-killing glass. That is of course why the Minnesota Vikings are not going to be playing in it in the Super Bowl. If there were any question that it was the Curse of the Bird-Killing Glass that doomed the Vikings, the fact that the team was dispatched by Eagles should dispel all doubt.

Dr. Daniel Klem of Muhlenberg College in Pennsylvania has spent his entire career studying the issue of bird collisions with glass, starting in the 1970s when not one conservation organization considered the problem a serious one. After decades of research, when he presented a paper suggesting that his conservative estimate of the number of birds killed at windows annually in the United States was between 500 million and a billion, some prominent ornithologists pooh-poohed his conclusions. But as they finally started doing their own research into the issue, their own studies affirmed Dr. Klem’s numbers and the horrifying magnitude of the problem. Windows and house cats, like heart disease and cancer, are indeed the top outright killers of birds in the United States.

In recent decades, Dr. Klem has been tirelessly working with glass manufacturers to come up with glass that is visible to birds. On the Muhlenberg campus, some of the glass is fritted—cut with a pattern making it visible to birds. Fritted glass has the additional advantage of being significantly more energy conserving than plain glass—both those factors led the Dallas Cowboys to build their new stadium using fritted glass.

Since 2012, all new construction built with public funds in Minnesota is supposed to meet sustainability guidelines, including energy conservation, that fritted glass would have met, but the building plans with energy squandering, bird-killing glass got grandfathered in despite the new requirements. Ever since the plans were first revealed in 2012, the birding and conservation communities tried hard to get the glass changed. My friend Sharon Stiteler, author of 1001 Secrets Every Birder Should Know, who is also known as Birdchick and is a long-time Vikings fan, was quoted by Gwen Pearson in Wired saying, “Holy crap, that’s gonna kill a lot of birds.” Dr. Klem said, “You’re building a bird killer.”

Although conservationists were supposed to be able to study birds killed by the glass, a January 31 article in USA Today pointed out that the 60 dead birds collected this fall were not the only ones killed. There was evidence that birds were disposed of by stadium employees, killed in inaccessible areas of the stadium, and removed by scavengers or the public. Injured birds may have flown off and died of head or spinal injuries away from the stadium complex. And there were days when no one was allowed near the stadium, and days when no volunteers were available to search for carcasses. So the estimate of 360 birds that could be killed by U.S. Bank Stadium in a three-year period “significantly underestimates true mortality,’’ according to the preliminary report.

Ironically, the exact same company that manufactured the glass for the Dallas Cowboys was under contract for the glass for the Vikings, too. Changing the contract when the problem was publicized would have cost about a million dollars more—less than a tenth of one percent of the more than billion dollar price tag. To fix the issue at this late date would cost $10 million. As Josh Peter wrote for USA Today Sports, “Some people will blame the “dumb birds.’’ But it’s the people who failed to address the problem years ago who are the real Dodo birds here.”

It can be prohibitively expensive to replace our windows with bird-safe glass, especially for regular human beings without public funding and a multi-billion dollar football franchise. But Jeff Acopian created Acopian BirdSavers, an affordable and extremely effective way we can treat the windows on our houses to make them genuinely bird safe. I talked to Jeff by phone this week; tomorrow I'll play part of our conversation about his wonderful Zen Wind Curtains.

Tuesday, January 30, 2018

Where Are the Birds?

For quite a few years now, I’ve been getting letters and emails from people wondering why they’re not seeing as many birds as they once did. I received one such email this week. Mike writes:

I feed birds a variety of seed, but have observed an obvious decline in numbers. Not as many Blue Jays, Pine Grosbeaks, and woodpeckers, and for the first time in years the redpolls have not found my nyjer seed feeder. I still see many chickadees and nuthatches. Is there a real reduction in numbers, or is it in my local area, or could it be something that I am not doing?Since it’s the last day of National Blue Jay Awareness Month, I’ll start with Nature’s Perfect Bird. Blue Jays are declining somewhat. Based on Breeding Bird Survey numbers since 1966, their numbers fluctuate here in Minnesota but show no overall decline.

An actual decline is more noticeable in Wisconsin:

and especially over the whole United States.

Redpolls, siskins, Pine Grosbeaks, and crossbills are "irruptive" species, so we expect big numbers some years and small numbers or even none in other years. But in irruption years, the numbers do seem to be lower than they used to be. This year, redpolls have been pretty abundant at the feeders in the Sax-ZIm Bog up near Meadowlands, but not in my yard. On Monday, Jan 22, about 250 showed up in my yard and remained for a few hours, but they disappeared at about 2 pm and that was it--not a single one since! It used to be that when redpolls were in northern Minnesota in good numbers, I always had at least a few in my yard, but as their overall population decreases, they can stick to more natural habitat without needing to spread into marginal habitat in town. Unfortunately, they breed further north than breeding bird survey road transects extend, so we don’t have data for them in summer.

Pine Grosbeaks are around in pretty good numbers in areas like Isabella and the bog, but I've only had a small group for an hour or so all winter. They don’t breed in the eastern United States. In Canada, their numbers swing wildly, but are trending downward.

|

| Breeding Bird Survey Trend: Pine Grosbeaks in Canada |

Pine Siskins also show wild fluctuations. In their case, especially survey-wide, they’re showing a significant downward trend.

|

| Breeding Bird Survey Trend: Pine Siskins in Minnesota |

|

| Breeding Bird Survey Trend: Pine Siskins in Wisconsin |

|

| Breeding Bird Survey Trend: Pine Siskins in the entire United States |

When flocking birds decline, they may seem as abundant as ever in quality habitat even as they disappear from more marginal habitat. So people in the best habitat are sometimes complacent as the birds decline in places like Duluth. Back in the '90s some listeners pooh-poohed me for complaining about Evening Grosbeaks disappearing, but now they've become rarities everywhere.

|

| Breeding Bird Survey Trend: Evening Grosbeak numbers Survey-wide |

On the other hand, cardinals and Red-bellied Woodpeckers are spreading north, so we can see more of them than we used to in our backyards.

I have had one or two Red-bellied Woodpeckers almost every day this year--they were extremely rare back in the 80s and 90s, but are expanding their range northward. They are more likely to be found in Duluth than in wilder habitat up here, because they mostly focus on hardwood trees, especially in the open habitat of neighborhoods rather than in genuine woodlands, and because one of the factors that helped them become established up here was bird feeding.

|

| Breeding Bird Survey Trend: Red-bellied Woodpeckers in Minnesota |

|

| Breeding Bird Survey Trend: Red-bellied Woodpeckers in Wisconsin |

|

| Breeding Bird Survey Trend: Red-bellied Woodpeckers survey-wide |

Cardinals have also expanded up here, and usually I have one or two at least, but this winter I've only heard them once from my yard--I haven't seen them in my yard at all yet. My desk where I work is set at a window where I can see many of my feeders, so I'm not missing much, but there hasn't been much to miss.

|

| Breeding Bird Survey Trend: Northern Cardinals in Minnesota |

|

| Breeding Bird Survey Trend: Northern Cardinals in Wisconsin |

|

| Breeding Bird Survey Trend: Northern Cardinals Survey-wide |

Except for the day that I had the redpolls, I've had very few regular birds in my yard this winter. But as the snow started falling on January 30, I started seeing more. And as birds deplete natural food resources through February and into March, more winter finches will turn up again, before returning north to breed. Those of us committed to helping birds take joy where we can. And Nature's Perfect Birds the Blue Jays, and our good old chickadees, spread joy no matter what.

Once in a Blue Moon

Just about every month, we have one full moon. Not every single month—this February will not have a full moon at all. To make up for that, January has two. Tonight’s full moon, the second this month, is what many people call a blue moon. And whenever a month has a blue moon, I declare it National Blue Jay Awareness Month.

Why should we be more aware of Blue Jays than of any other bird? This year March happens to have a blue moon, too—though oddly enough, that fourth full moon of the year happens to be called the pink moon. Maybe when the moon is pink, everyone should become more aware of the Pink-headed Warbler of Guatemala and Chiapas, Mexico,

or Lewis’s Woodpecker,

or the Pink-footed Goose,

or the most adorable bird in the universe, the Cuban Tody.

But there are only 12 months in the year, and at most only 13 full moons in a year. It would take almost a millennium to give every bird on earth its own awareness month, and more than 83 years to give just every bird in the United States and Canada its own awareness month.

Maybe instead of a whole month, we could give different birds their own awareness day. On the first day of winter, what Robert Frost called the “darkest evening of the year,” we should all grow more aware of crows, ravens, and other dark birds. Maybe on national holidays we should celebrate the Eastern Bluebird for its red, white, and blue plumage,

or the Painted Bunting because it’s more intensely red and blue even if it’s missing the white.

On Catholic holy days we could try to be more aware of Northern Cardinals, who were given their name for their color, which matches the garb of Roman Catholic cardinals.

If we devoted a single day to each species, it would take almost 28 years to give just our North American species their due. Over the 32 years I’ve produced For the Birds, I’ve archived 3,072 programs, in which I’ve mentioned 785 different species at least once. I’ve talked about Blue Jays, or at least mentioned them, in at least 348 programs, and about Black-capped Chickadees at least 409 times. Even during National Blue Jay Awareness Month, I figure a day without chickadees is a day without sunshine, yet my favorite bird appears in only about 13 percent of my programs.

I wish more of us were aware of more birds, from the common species in our everyday lives to the more secretive or rare ones, like owls, that we thrill at whenever we do luck into seeing one, to the ones that most people haven’t even heard of—the species that eke out their existences in our state, even our city, without most of us ever noticing. This world has so many real treasures, living and breathing gifts of inestimable value even if we get so consumed by materialism that we are blinded to so much that really matters. That’s why I started producing For the Birds in the first place, but also why I decided to create a National Blue Jay Awareness Month. It’s nice to focus a lot of attention on one common species, at least once in a blue moon.

Blue Jays aren’t likely to notice tonight’s full moon, or the lunar eclipse that will begin, at least the penumbral phase, at 4:51 am tomorrow here in Duluth, Minnesota. Unlike nocturnal migrants, Blue Jays tend to sleep through the night year-round. When I rehabbed and through all the years that I had my education Blue Jay Sneakers, I never noticed a jay stirring once it got dark. But if we humans wake up early and there aren’t clouds in the west, we may notice that moon will start turning red as the partial eclipse phase begins, here in Duluth at 5:48 am. Totality won’t start until 6:51, as the sky is brightening, and the maximum eclipse will start at 7:29, just 7 minutes before the moon sets here. People east of us will see even less of it.

Blue Jays will be waking up during the eclipse, but we’ll never know if they noticed. It’s a pretty safe bet they know nothing about blue moons, which are defined by our human calendar and acknowledged by only some of us anyway. Beyond that, we simply do not know what Blue Jays, or any other birds, think about celestial matters. Chickadees, nuthatches, and woodpeckers, sleeping in cavities, don’t see much of the moon at night ever, and I don’t know if they notice the moon in the daytime sky, either. What goes on in birds’ minds is a true mystery to us humans, with all our anthropocentric limitations. Brooks Atkinson wrote:

Although birds coexist with us on this eroded planet, they live independently of us with a self-sufficiency that is almost a rebuke. In the world of birds a symposium on the purpose of life would be inconceivable. They do not need it. We are not that self-reliant. We are the ones who have lost our way.

Thursday, January 25, 2018

Our Far-Flung Correspondents: Owl tragedy

|

| David Bartlam found this poor dead Great Horned Owl in Proctor, off I-35. |

On Tuesday, I talked a bit about the many northern owls turning up in the Duluth area recently. Tragically, not all the owl sightings have been happy. I’ve heard a few accounts of Snowy Owls being struck by cars, and of a Boreal Owl found dead. But perhaps the saddest story was sent to me by David Bartlam, who came upon a dead Great Horned Owl in Proctor along I-35. The poor bird must have been flying with its legs dangling, as owls so often do, and one toe got snagged in a chain link fence. David wrote that it was extremely cold that day, which would certainly have hastened the owl’s death. He returned four hours later, but the owl’s carcass had been removed. He sent the photo above.

Good fences may make good neighbors in Robert Frost’s world, but not in the world of owls. Flying in the dark as they do, they know how to recognize and avoid dangerous obstructions in their airspace such as trees and buildings, and know from experience that just about everything at fence height—grasses, weeds, and the twigs in the upper parts of shrubs—is invariably yielding. The first time they hit a fence is usually the last. In December 2010, I got a heartbreaking message from Mary-Ellen Holmes, on her farm south of Superior. She’d found a Great Horned Owl electrocuted and frozen solid on her electric fence. It was stunningly beautiful and so lifelike except for being dead. She sent the poor thing to a nature center for education.

When I went to the visitor center at the Wheeler National Wildlife Refuge in Alabama, someone had just delivered a Barn Owl that had collided with a barbed wire fence. It was impossible to safely extricate the bird from some of the wires, so the person who rescued it cut the wires in place. Refuge personnel were going to send the bird to rehab, but I’m not sure it was going to make it. It’s important for our own peace of mind as human beings to do what we can to help our fellow creatures on this little planet, even when it may well be futile, if we want to preserve our own humanity.

Fortunately, not all owl-fence collisions are fatal, but when an owl is entangled, time is of the essence. In 2010, the Duluth News-Tribune reported that Kathy Paquette of West Duluth had found a Northern Saw-whet Owl ensnared in the mesh fence surrounding her garden. Fortunately, she found it while it was still doing well, untangled it, and brought it to an area rehabber. This bird was held for observation overnight, and released at Paquette’s place the next day. The paper quoted her, “Oh, my god,” she said. “That was a dream come true for me. I love animals. I like to save animals… I was in tears, I was so happy I found him before he was dead,” she said.

I was with a birding group in Arizona back in the 1990s when we came upon a Barn Owl whose leg had been snagged in a barb on a fence. We couldn’t tell how long it had been there, but it was early in the morning on a day that ended up being very hot. It took both Kim Eckert and I, who had both handled lots of raptors, to free the poor bird. It had a couple of serious gash wounds and was going into shock. Luckily we were in time, and the rehabbers were able to release it where we’d found it several days later.

Collisions with fences are the number one cause of death for female prairie grouse, and certainly a significant cause of death for owls. When fences are providing an important function, they obviously need to be kept in place, but when that function is over, it’s time to take them down. David Bartlam wrote, “I can't tell you how many times I have been with a dog that is running through the woods and crashes into an obscured fence, so I am sure it takes its toll on other wild creatures. The problem is the longevity of steel fences.” My own golden retriever, Bunter, got badly injured on an old barbed wire fence that had been discarded and rolled down a ravine long before. Removing and properly disposing of unnecessary fencing is work, but it’s also the duty of responsible landowners. Even in Robert Frost’s universe, it’s only good fences that make good neighbors.

Wednesday, January 24, 2018

Happy 99th Birthday to My Mother-in-Law

Ninety-nine years ago today, my mother-in-law, Helen, was born in Andersonville, the Swedish neighborhood in Chicago. Her mother, an immigrant from Sweden, died just four days after Helen was born, while Helen’s father was fighting in World War I, so one of her mother’s friends took care of her. When Helen’s father returned from the war, he wasn’t in a position to care for a small child, so she remained with her foster mother for several years. When her father married, Helen didn’t want to leave the only mother figure she’d ever known, so she stayed put until her foster mother died. Then she moved in with her father, stepmother, two half-brothers, and half-sister. During the Depression, the children often spent their summers with relatives in Port Wing, Wisconsin, where Helen met my father-in-law. They wrote to each other during World War II, and married after the war.

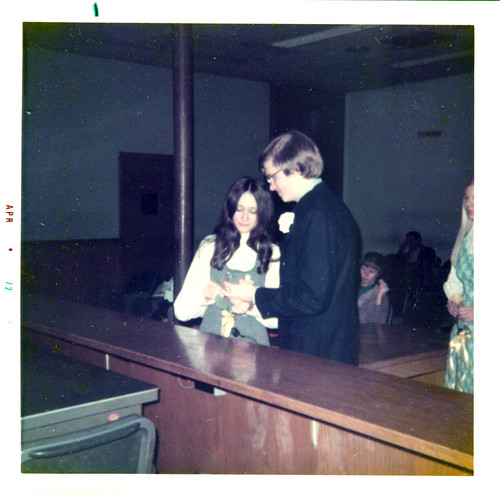

Russ and I started dating the summer before our senior year in high school, and from the very start, his parents made me feel like a part of the family. We started out at different colleges—Russ at Michigan State and me at the University of Illinois—but I switched to MSU when we decided to get married during our junior year. I was on my own at 19 anyway, so my parents didn’t figure into the decision, but nevertheless, getting married so young was more impulsive than we realized. Russ’s parents gently tried to talk him out of it, but 20-year-olds always feel wise beyond their years, and his parents handled it all gracefully and generously. Russ’s mom loved the trappings of beautiful weddings; our cheap, simple wedding before a judge, with just twelve people present counting us and the judge, seemed inexplicable to her. But she never once criticized our choices.

I made my own simple jumper and Russ’s trousers with the same blue denim knit fabric—about as far from traditional wedding garb as one could go. If Russ's parents came to the obvious but erroneous conclusion that we were rushing things because I was pregnant, they never voiced the thought; our first baby didn’t come along for almost ten years.

Russ told his mom to buy me binoculars and a field guide for Christmas in 1974, but she did much more than just that to get me started birding. She took me to lots of birding spots in Chicago, such as the Morton Arboretum, the Little Red Schoolhouse and Crabtree Nature Centers, Baker’s Lake, and various forest preserves. She never kept a life list of her own birds, but she was wonderfully happy whenever I got a lifer. After she and Russ’s dad bought their place in Port Wing, during the time they were fixing it up and then after they moved there, I’d come visit to take long walks through the best habitats, and she was always ready to sit down and hear about the birds I’d seen and heard. She also kept me apprised of all the birds she was getting at her feeders.

From the moment I started producing "For the Birds" in 1986, Helen was my most faithful listener. She especially enjoyed when I referred on the air to my father-in-law as the president of the Port Wing Blue Jay Haters. She continued listening every morning on KUMD until just a few years ago, when her poor hearing made it too frustrating.

I was never a very good day-to-day cook, so for the most part, Russ took over that responsibility. I very clearly didn’t fit his mom’s idea of a housewife, but she never seemed to expect me to be one. Indeed, one time when she and I went to lunch at her friend's house, Helen carried in a bunch of stuff and handed me the container with her freshly-baked cookies. Her friend took them at the door and said they looked wonderful. "Did you bake them, Laura?" Before I could say a word, Helen jumped in and said, "Of course not! Laura has too many important things to do with her life than sit around baking cookies!"

As far as domestic skills go, she considered me her adorably ditzy daughter-in-law, and over the years, I could sometimes see a little smile on her face when I messed up some simple homey task. I probably had that same smile on my face when she misidentified a bird. We were wonderfully well suited, fond of each other not despite one another’s shortcomings, but somehow because of them.

|

| Helen and me in 2014 at the Port Wing Fall Festival |

Russ’s dad died in 1992; Helen continued to live in her house in Port Wing until 2012. During the time she was on her own, she was the most self-sufficient person I’ve ever known. I stayed with her 24-7 at a few points while she was in her 80s and early 90s when she was sick, and when she had a crippling case of bursitis in 2012. That time I spent one full day away doing a Big Day fundraiser starting and ending in Washburn. I got back to her house after 10 pm, when she’d normally be heading to bed, but as I came in the door, she went straight to the kitchen and cooked me up a dinner. I tried to convince her that I was perfectly capable of making my own meal, but despite the pain she was in and her inability to stand straight, she smiled with that familiar twinkle in her eye. I’d spent my day in my own milieu, but now I was on her turf, back to being her ditzy daughter-in-law.

Little by little, her body was growing more frail and dementia was setting in, so we brought her to live with us in Duluth in December 2012. Over these past years, she’s lost more and more memories and become increasingly detached from some of her old interests. She hardly ever looks out at the birds in our feeders anymore, but she can still play and win at Uno when our family gathers at Christmas, and she still figures out some of the Wheel of Fortune puzzles before I do. She reads and does crossword puzzles and jigsaw puzzles every day, makes her own breakfast and lunch (though we have to make sure she remembers), empties the dishwasher, and sets the table. I do physical therapy exercises with her each afternoon, and watch various movies and TV shows with her every evening.

Our old house, with its small rooms, narrow hallways, and tight corners, can’t be negotiated with a wheel chair or even a good walker, so we’re dreading a future when she can’t get by with a cane anymore. But for now, we’re managing surprisingly well.

It’s been very hard for this supremely self-sufficient woman to find herself being taken care of, which makes me sad. But she hasn’t entirely lost her spark of independence. Russ had to go out of town a couple of times in the past couple of months, which meant I cooked our dinners every night. When she sat down, waiting for me to serve, she got that familiar twinkle in her eye, just knowing her ditzy daughter-in-law would do something wrong. And sure enough, I’d forget her toast or her margarine, or overcook the vegetables, or mess up somehow. It doesn’t take much to make her happy. Helen may be 99 years old today, but one thing she will always be able to count on is her ditzy daughter-in-law.

Tuesday, January 23, 2018

Owls!

If there is a month during which we should not be seeing owls all over the place, it’s National Blue Jay Awareness Month. Blue Jays do not approve of owls in any way, shape, or form, with good reason. Owls as small as Eastern Screech-Owls eat Blue Jays, so when a Blue Jay discovers any owl, it voices its disapproval loud enough to alert jays and other critters, far and wide.

Since the start of National Blue Jay Awareness Month, I’ve seen only a single Blue Jay on two occasions—one visiting my feeder briefly on January 3, and then that one or another on January 22. I’m glad they’ve been few and far between this year, because we’ve been seeing lot of owls. I’ve seen Snowy Owls a few times in Canal Park, and one magnificent adult male along the Western Waterfront Trail—three crows, close Blue Jay relatives, were chasing that one.

Northern Hawk Owls and Great Gray Owls are being seen at the Sax-Zim Bog and here and there up the shore a ways. They are easiest to find on cloudy days, but birding is like a box of chocolates—even on a sunny day you never know what you’re going to get.

The most sought-after owl in northern Minnesota, and also the one most likely to eat Blue Jays, is the Boreal Owl. A few have been seen in and near Duluth this winter. One hung around Hartley Nature Center on and off for a couple of weeks. I was lucky enough to see that one late one cloudy afternoon when she was actively hunting,

and earlier one sunny afternoon when she was roosting.

A Boreal Owl may appear almost anywhere—they’re most often seen roosting along the North Shore but you never know when one is going to turn up in someone’s backyard. They’re most often noticed by tracking down swearing chickadees or Blue Jays. It’s important not to disturb them when they’re roosting: if chickadees notice their open eyes, they start piping out tiny obscenities that alert larger, more dangerous birds to attack. So the owls are safest when allowed to sit tight with their eyes barely open.

Last week I went to Hartley with a small group in hopes of spotting the Boreal Owl. That day it was supposed to be near the bird feeders by the building, and there was a sign on the gate entrance to that area asking people to keep their distance if they saw it. We stepped in and walked pretty close to one feeder—that’s when I got my best photos of Black-capped Chickadees and Red-breasted Nuthatches for the day.

We scanned the trees all around, and then started back to the gate. That’s when Erik Bruhnke spotted the Boreal Owl—not only had it been in view all along, if only we’d looked on the right branch, but it was sitting directly above where we’d walked in! Of course, we weren’t the only ones who had missed it—the chickadees and nuthatches were zipping right past it, some just inches away, without missing a beat.

To leave the feeding area, we had to get closer to the owl than I like, but there was no other way out. We took photos with each step as we worked our way out. Too many birders can’t help but make squeaking sounds or get even closer in hopes of eyes-open photos, but making them open their eyes for our entertainment is the height of rudeness.

Barred and Great Horned Owls are presumably around in normal numbers, but I haven’t lucked into seeing either one yet. There could be a Northern Saw-whet Owl somewhere, too, but I’ll wait to start searching seriously for them in April when they’ll be calling. Meanwhile, even during National Blue Jay Awareness Month, there are plenty of other owls out there. And despite them, maybe even a Blue Jay or two.

Subscribe to:

Comments

(

Atom

)