|

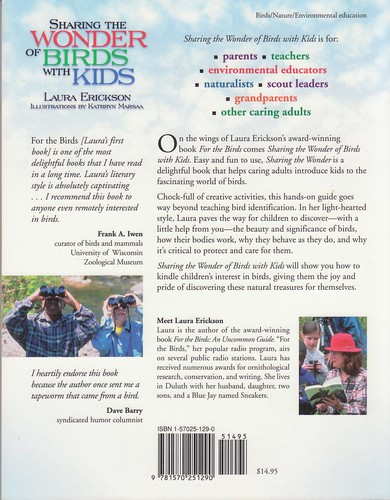

"Dad," the male Great Blue Heron who nested in Sapsucker Woods every year from 2009-2014.

This is the last photo I took of him, in 2015.

|

In 2009, during the time I worked at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, a pair of Great Blue Herons built a nest in a long-dead white oak in Sapsucker Woods Pond, and successfully reared 4 chicks. That January, I’d bought my first DSLR camera, so I was spending all my breaks and lunches walking around the pond taking photos. I got hundreds of photos of one extremely cooperative heron as he preened, fished, and stood stock still as if posing for me. One of my favorite photos, though also one of the most tragic, shows an adorable little fish in its last moment of existence, mid-air between the heron’s huge mandibles.

I started being able to verify that virtually all these photos were of the same individual, because he was missing a hind toe and a front claw. When I started photographing the nesting herons, I realized the male was the very heron I’d photographed so often. I grew inordinately fond of him.

Watching the heron nest from even the best vantage points in the building or outside, we couldn’t see how many eggs were in it, if any, and had no clue when they hatched until we saw a tiny fuzzy chick head. A day or two later, we saw two at the same time, and then three. They all had to be standing tall at the same time for us to get a count, and it was over a week more before we saw all four. After they were big, we could easily count the four of them until they fledged. After that, we could still check up on them because the parents fed them only in the nest. It took a while for them to learn to find their own food, so one or two might fly up to the nest occasionally in the daytime, and all four gathered before nightfall to sleep up there. I started walking to the Lab from my apartment every evening, only able to sleep well after I’d made sure all “my” babies were accounted for.

Visitors and contributors to the Lab were enthralled with the photos of the Sapsucker Pond Great Blues, so I suggested they put a nest cam there before the next season—this was at the peak of popularity for the Decorah Eagle cam, and no one had ever set up a cam for a really close look at nesting herons before. The guy in charge of managing such things mansplained to me why that was utterly impossible, but of course in 2012 when the Lab did construct a nest cam, he got all the credit. So it goes.

Having that wonderful up-close and personal look at the parents and chicks gave me so much understanding and appreciation for how herons raise their young. Each parent spent a lot of time away from the nest fishing. When the chicks were first hatched, often the parent returning to the nest would brood them or just sit on a big branch, taking up to an hour to digest before regurgitating a pile of stomach contents into the nest. As the chicks got older and more capable of doing their own digesting, the parents regurgitated the food more quickly, and some of the fish even became identifiable. One time a large gold carp was still alive when the male vomited it up—whenever one of the baby herons touched it, it thrashed for a few seconds. Somehow my brain turned off my empathy switch regarding the poor fish because the moment it moved, the almost-full-sized baby herons were so shocked that they all lurched back and stared in amazement. It had clearly never, ever occurred to them that food could be alive.

But virtually the only animals in the regurgitated pile of baby food that the parent herons brought back were fish. A quite dead vole did appear in the pile once, but the suspicious babies would not swallow it, and finally one of them tossed it out of the nest.

Meanwhile, the Lab had also placed a nest cam on a Red-tailed Hawk nest on campus. I didn’t like watching that one—it was one thing to watch herons regurgitating fish, quite another to see what the hawks brought home, which included a lot of chipmunks and rabbits, occasionally still alive. I’m just too fond of little mammals to watch that.

As one of the monitors in Cornell's Heron Cam Chat Room who also fielded a lot of questions sent to the Lab, I started hearing people claim that some Great Blue Herons specialize on chipmunks. I had misgivings the first time someone told me a heron was coming and taking the chipmunks at her feeder, but after hearing more than a dozen accounts, I had to accept these accounts as truthful oddities.

Then this week, Heidi Holtan at KAXE forwarded me an email from Lynn Hanske in Baxter, Minnesota, who wrote:

Thought you might be interested to see this video I took in my backyard of a Great Blue Heron last Friday. This was the 4th chipmunk in about 25 minutes. S/He has been back every day since and we’ve seen him catch and consume 12 so far! Once he gets one, he walks it quickly down to the lake, shaking it the whole time, then dunks it in the lake and swallows it in one gulp.

Lynn kindly gave me permission to post the video on my blog. Tragically, Blogger says it's too large of a video file, but I can at least provide

a link to the .mov file.

I got nervous when I watched the start, with the heron walking directly toward a chipmunk eating some breakfast, but the little guy noticed and hightailed it out of there in time. When the heron got that one or another, the worst of it was hidden behind some ferns. It’s interesting, so if you aren’t too enamored of chipmunks, check it out.

Then Lynn sent another, longer video wherein the first chipmunk the heron grabbed managed to get away; the video kept going, and the heron did get that chipmunk or another. Who knew the lives of chipmunks were so fraught with danger? (

Here's the link to that .mov file.)

One of my friends, Christina, mentioned that the herons at Point Reyes in California seem to feed mostly on rodents, and since the years of the heron cam at Cornell, I’ve heard so many other accounts of herons taking various rodents that it no longer surprises me, even though Lynn’s videos disconcerted me. Much as I love Great Blue Herons, especially since growing so very enamored of that one individual at Cornell, chipmunks are the adorable little guys who live in my own backyard. Predation is an important part of nature, and I’m appreciative of whatever Great Blue Herons do to thrive, but sometimes my best strategy is simply to avert my eyes.

By the way, Lynn Hanske is also seeing a family of Wood Ducks visiting her feeders, including one odd little duckling. Apparently a Hooded Merganser lost her own nest and had no other place to lay an egg ready to pop out, so she deposited it in the Wood Duck nest. That one little Hooded Merganser duckling has no clue what to do at a feeder. Unlike Wood Ducks, who eat acorns and other terrestrial food items, mergansers eat fish and aquatic insects pretty much exclusively. We’re hoping the little guy is getting plenty enough food when the mother takes the ducklings to the lake, and stays out of the striking zone of a certain Great Blue Heron. Lynn will try to keep track of how the little one fares.