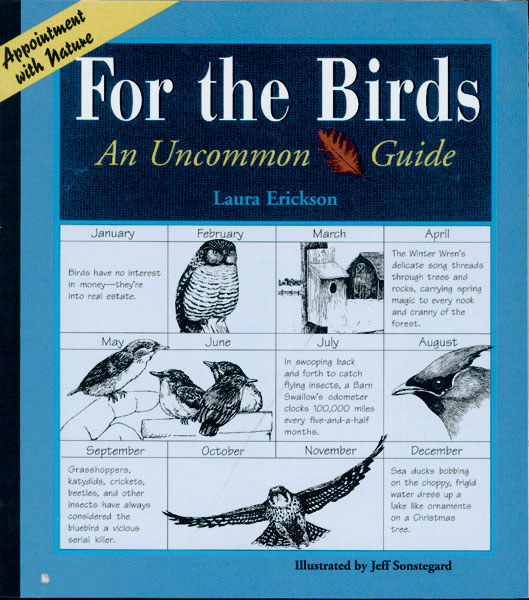

In the fall of 1992, I got a request from Don and Nancy Tubesing, owners of Pfeifer-Hamilton Publishers, a small Duluth company, to write a book based on my radio program. It would be their second book in a series they were calling “Appointment with Nature”; this one would be titled

For the Birds: An Uncommon Guide. What they wanted was very specific—365 short essays, each with a sidebar, one for each day of the year. And they wanted it

fast—I signed the contract in November and they wanted the completed manuscript by the first day of spring.

It wasn’t quite as rushed as it sounds. I’d been doing my radio program, “

For the Birds,” for more than six years by then, which is why they knew of me and knew I had the kind of material they wanted.

About a third of the book was drawn directly from whittled down program transcripts, another third involved significantly revised scripts, and a third was written from scratch. I had to stay focused and on task every single day for four months, averaging slightly more than 3 polished entries a day, in order to finish in time.

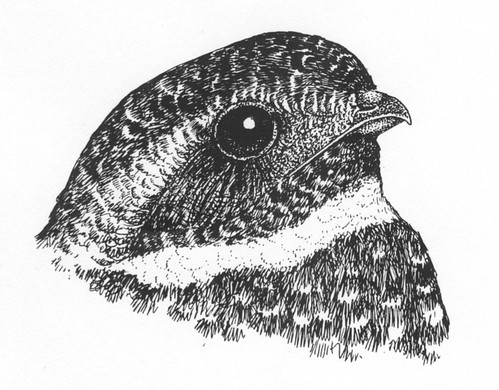

But before I could even start writing, I had a lot of organizational tasks. Every page was going to have a small drawing by the late Jeff Sonstegard, who needed to know what every page topic was going to be early on.

|

| Of all the drawings Jeff Sonstegard did for the book, this was my favorite of all: Fred, my education nighthawk. |

Jeff also would be producing a dozen larger drawings to go on the opening page for each month.

Those drawings would also be printed in paler form at the bottom of each daily entry.

Jeff needed to finish the large format drawings by January, and all the rest of them by early April, which was a major endeavor. So I needed first to settle on appropriate themes and species for each month, and then plotted out the topics of all 365 essays so he had them early on.

To accomplish this, I got a loose-leaf notebook and drew into each two-page spread a generic month calendar, each day’s square sized to fit a post-it note. I put in some obvious date-related topics first. I wanted to start the year with the Black-capped Chickadee. For Russ’s and my children’s birthday entries, I wrote about their favorite birds. I didn't write the book in order, but could mark each of the 365 post-it notes as I finished each essay/sidebar, so I never lost track of what still needed to be done.

|

| Of all the essays I wrote for "For the Birds," this one about the Snowy Owl, placed on Russ's birthday, was the one I was most asked for at readings. |

Oddly enough, even though I'd specifically put Russ's and my kids' favorite birds on their birthdays, it never occurred to me that a great many people looking it over in bookstores would immediately turn to

their birthdays. I once received an email from a man with a February 18 birthday who was delighted that his birthday entry was about plastic lawn flamingos.

I can't remember anyone with a November 3 birthday telling me about their reaction to the topic on that day--tapeworms!

I wrote about the Passenger Pigeon on September 1, the anniversary date of the death of Martha, which marked the species’ extinction. I wrote the April Fools Day entry as if Big Bird were a real species. I wrote about starlings on Shakespeare’s birthday, because their introduction to America was inspired by a club trying to honor Shakespeare by releasing in America every bird mentioned in one of his plays. Here and there were a few other date-related topics.

I also had to keep all the essays properly seasonal. I needed each one to stand alone, but I figured most people would read it in order, so I also wanted the book to build on what had come before rather than be static or random. The January entries included basic information about bird feeding, I put tips about birdhouses in early spring, and wove in lots of conservation information throughout, trying not to be heavy handed, and building up so my largest messages about the perils birds face would be near the end, trusting that by then readers would care more about their plight.

I also set as a task to end the book with the word “love,” but also with my best one liner joke—the essay/sidebar format was perfect for that.

|

| The sidebar ends with my best one-liner, the main essay with the word "love." |

It took a while to plot out all 365 topics, and as I got writing, I got new ideas, or had a sudden reason to move a topic to a different date. So I kept in close communication with both my editor and Jeff, and gave Jeff the high-priority drawing topics first—the ones I was absolutely certain would be in the book. I researched out most of the reference photos he used, too.

The book ended up selling great guns thanks to how beautifully it was produced by Pfeifer-Hamilton and how effective their marketing team was. And they

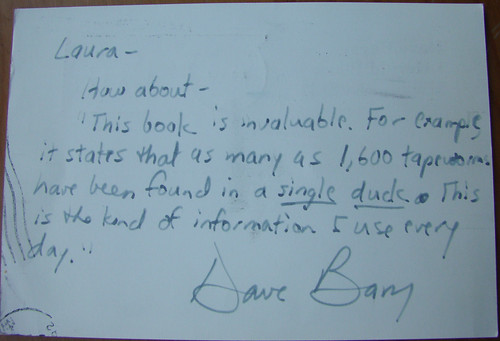

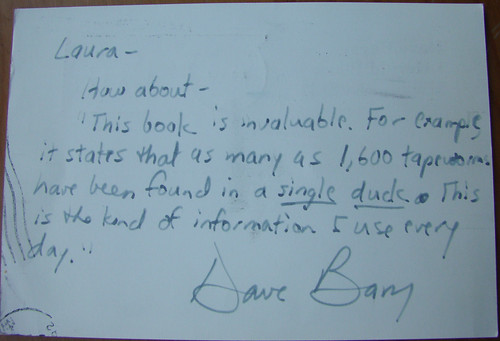

were effective. They managed to get wonderful blurbs from such luminaries as Chandler Robbins, Frank Gill (who'd written the ornithology textbook that was then and, in updated editions, is currently still in use in university ornithology classes), Joe T. Marshall of the Smithsonian, and even Pulitzer-Prize-winning humorist Dave Barry.

|

| This is the endorsement Dave Barry wrote: "This book is invaluable. For example, it states that as many as 1,600 tapeworms have been found in a single duck. This is the kind of information I use every day." |

Thanks to that great marketing,

For the Birds, released in September 1993, sold out the first week. (I am not making that up.) A rushed second printing sold out before Christmas. Those two printings had been for 5,000 books each, so the third printing was for 10,000, and by 1995 it went into a fourth printing, again of 10,000. The Tubesings retired just a few years later, and the University of Minnesota Press picked up both

For the Birds and my second book,

Sharing the Wonder of Birds with Kids (winner of the National Outdoor Book Award). Both titles are still available. Unfortunately,

Sharing the Wonder is badly out of date, and some information in

For the Birds isn't accurate, either.

Two editorial changes made by Pfeifer-Hamilton's out-of-house copy editor still rankle. On the page about gynandromorphs, she researched some inaccurate information about sex chromosomes, and changed what I'd correctly written as the W and Z chromosomes to X and O chromosomes; my publishers accepted her change. Now that whole essay is out-of-date anyway, because it's been discovered that bilateral gynandromorphic birds are actually chimeras--two embryos fused together into one single individual.

Another change was even more irritating, for different reasons. After explaining that the skeletons of "bird-hipped dinosaurs" were more similar to birds than to other reptiles, I ended the essay about birds and dinosaurs with this:

It's hard to explain extinction to a small child. Even if dinosaurs were true reptiles rather than birds, it's appealing to look at a tiny chickadee and imagine that it embodies the spirit, and maybe something of the physical presence, of a lumbering Brontosaurus.

Annoyingly, the copy editor had read somewhere that

Brontosaurus was no longer considered a valid dinosaur, and she changed the final phrase to the woefully unalliterative "lumbering

Apatosaurus." Pfeifer-Hamilton would not allow me to change it back--the best I could do was change the species to

Brachiosaurus. It wasn't too long afterward that Stephen Jay Gould published his

Bully for Brontosaurus. I still get mad thinking about this one even though—I know I know I know—

Brontosaurus was not a bird-hipped dinosaur, anyway.

As big an ego trip as it was for me when

For the Birds became a regional best seller and won some awards, it was exhausting to write. Because of the design constraints, I had no flexibility at all regarding how long each essay could be. Some topics deserved more in-depth treatment than a single page could offer, so one of the most time-consuming elements in the writing was paring those down to essentials. I became a master of conciseness. In a few cases, I could give a storyline the space it deserved by stretching it over two or even three days. In those few cases, I worked very hard to have each stand on its own even as I knew that group of essays would be best read in a single reading, or at least consecutively. I certainly didn’t want to waste words and space telling the reader the story would be continued in the next essay, and also didn’t want to waste space referring people to related essays on other pages—that’s what indexes are for. I made sure my terminology was self-explanatory even when I covered a concept in more depth elsewhere. This was a fun challenge, and the heavy editing it required for me to keep each page to the exact size needs made me see firsthand that most of the time, cutting away words makes writing better.

Nevertheless, even as I developed more skills at being concise, and even as I appreciated that this format was exactly right for a calendar book, I was drained by the time it was finished, and decided I’d rather have more breathing room to treat topics with as many or as few words as the topic deserved rather than as the page format dictated. My

101 Ways to Help Birds included, essentially, 101 essays, but was laid out so it worked even with some essays less than a page while one runs almost 20 pages.

I’ve been even more constrained by page design in a few other books I did, most notably my

National Geographic Pocket Guide to Birds of North America and my

American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Minnesota. As in a calendar book, page design in a field guide is critical, with space constraints baked into the recipe. Fortunately, the formats of most of my other books have been flexible.

I’m writing about this right now because I’ve been reading a book with as tight a design model as

For the Birds, but without any compelling reason for it. And on most pages, that book refers the reader to at least one and as many as five or six different pages—on one single page, there are eleven!—breaking up sentences and paragraphs that otherwise would read beautifully, and it’s been driving me crazy. I’m not naming names—I doubt anyone else will even notice that about the book. But I find it irritating and even hurtful that that writer’s agent rejected out-of-hand a book proposal I sent him a few months ago about a collection of my

“close encounters” essays. Without reading a single one, he said no one is interested in books of essays anymore. I guess my reaction to this new book he himself represented supports his decision.

Meanwhile,

For the Birds continues to sell a few copies each year, and I still hear from people who love it. In 2011 when I was at a booksigning event in the Twin Cities with my then-new book

Twelve Owls, a couple asked me to re-sign their first edition copy of

For the Birds.