Yesterday I inaugurated my Best Bird EVER! ™ series talking about the very first Blue Jay I ever saw. Even though this is National Blue Jay Awareness Month, March 2 is Chickadee Day for me, because it’s the anniversary of the very first Black-capped Chickadee I ever saw. Most of Laura’s Best Birds EVER! ™ weren’t lifers—something more important than just being the first time I ever saw one made them memorable. But the very first day I set out with my first field guide to try to find a bird was a make or break situation, and one cooperative little individual inviting me into the world of birding made all the difference.

Russ’s mom gave me my first field guide for Christmas 1974—it was the Peterson guide, and I read it cover to cover. Then I bought and read the Golden Guide cover to cover. That was information overload. In the middle of the Golden Guide, I saw a slate-colored bird with a white tummy and white outer tail feathers. I thought that plumage was wonderfully distinctive, and that it would be impossible to mistake the Black Phoebe for anything, but toward the end of the book, there it was again, only it was now called the Slate-colored Junco.

Reading the text, I could see that the Black Phoebe wagged its tail and that its black bill wasn’t shaped like the pinkish, conical bill of the junco, and the map for the Black Phoebe showed it didn’t come anywhere near Michigan where I lived, but it was disconcerting to say the least to see that birds that had such a similar color pattern could be entirely unrelated. I could also see that loons and grebes, which sure looked like ducks to me, and coot and gallinules, were far apart, in different directions in the book, from the ducks; that the herons and cranes were spaced far apart but looked similar; and that the gulls and terns looked a lot like seabirds that were in entirely different sections. I had no idea how anyone could learn them all.

I finished the books in late February and set out on March 2 to start birding. I went to Baker Woodlot on the Michigan State University campus, and spent a long time—at least a half hour and probably closer to 45 minutes—searching for a bird. It’s funny to think back from this vantage point, when I can hardly step out of my car anywhere in the Midwest without hearing at least one bird. Until natural sounds became distinct voices for me, they were just part of a general soundtrack of the outdoors that I’d never made sense of.

But I walked here and there on the trails, and finally, there it was—a bird! It was very active, flitting from branch to branch, and tree to shrub. I was pretty sure it wasn’t going to be in the first half of my Golden Guide, but didn’t feel confident of that, so I started at the very beginning and rifled through the pages. In the middle, I found a whole page of birds that looked almost identical, and just like my little bird, which stuck around, still flitting about close by. Those birds were all called “chickadees,” but what if there were other birds with black caps and throats and white cheeks? I stuck my index finger in the page and kept going just in case.

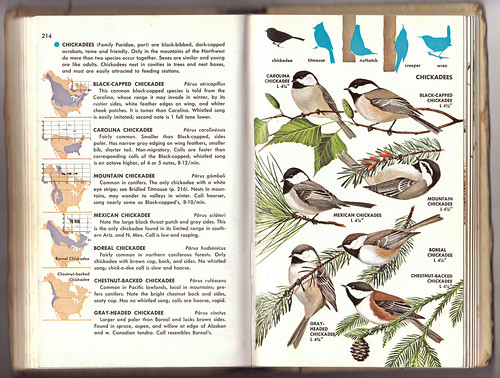

But there weren’t any other birds like this one, so I went back to the chickadee page. The Mountain Chickadee had a line through its eye, the Boreal Chickadee had a brown cap, the Gray-headed Chickadee had a gray head while mine had a shiny black cap, and the Chestnut-backed Chickadee was rusty brown, not gray on the back. So that left me with three choices. Fortunately, my little bird was sticking around while I studied the book. The Mexican Chickadee lived too far away.

But how could I pick between the Carolina Chickadee and the Black-capped Chickadee? I was in southern Michigan, which seemed further north than the range of the Carolina Chickadee, but the map didn’t show state lines, and these were birds, so I presumed they could fly about if they wanted—indeed, the description of the Black-capped Chickadee said that the ranges could overlap in winter. One hint of the Black-capped that the book mentioned was “It is tamer than Carolina,” and my little bird sure seemed tame, sticking right by me still. But most of the differences seemed both subtle and requiring familiarity with both in order to decide—the Black-capped had “rustier sides, white feather edges on wing, and whiter cheek patches.” That seemed pretty subtle and tricky.

Based on the descriptions, I could have easily chosen between them had my bird sung the Hey, sweetie! song, but it didn’t. It did make a lot of chickadee-dee-dee calls, and according to the book, the Carolina Chickadee’s “Calls are faster than corresponding calls of the Black-capped.” I couldn’t hear both to make a determination, but I listened hard the whole time my little bird stuck around, and when it finally flitted off into the woods, I raced along the path back to my car and headed straight to the university library to listen to recordings. For certain, it was a Black-capped Chickadee, Number One on my lifelist.

How could my first experience teasing out a bird identification have possibly been better? Every time I flipped through my book, I grew a bit more familiar with the layout and the possibilities. To figure out my first one, I needed to use the maps, plumage descriptions, descriptions of songs and calls, hints about behavior from both the text and noticing how the various chickadees perched in different ways in the illustrations, and also learned to use the university’s listening library. I couldn’t have been certain about my first bird’s identity had it not been so cooperative, sticking by me as I went through that long, deliberative process. At the time, I didn’t know a single experienced birder, so when I did figure it out, there was no one to ridicule my ignorance, taking so long to figure out a simple chickadee, and meanwhile, there was that memory of the friendly little bird chickadee-dee-dee-ing so close to me for so long, the most patient teacher in the world, as if it was specifically trying to welcome me into the world of birding.

From the very start, chickadees were far more than just a bird to identify and add to my lifelist. That very first chickadee I ever saw seemed cheerful and friendly and somehow almost as interested in me as I was in it. Throughout that first spring and then the rest of the year, and for the 43 years to follow, just about every time I went out birding anywhere in that great big range where Black-capped Chickadees live, I could find them. This was a bird I could count on, through thick and thin, as I embarked on a lifetime of birding. And it all started with one approachable, friendly, and welcoming individual. Yep. That first Black-capped Chickadee was Laura’s Best Bird EVER! ™