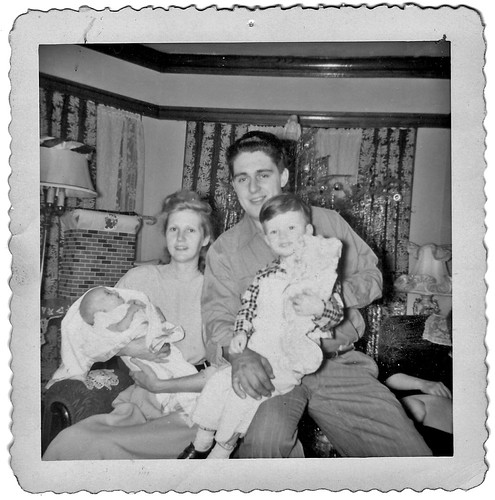

On September 1, 1980, which happened to fall on a Labor Day just like this year, my brother called me up first thing in the morning—our dad had just collapsed and died of a heart attack. It was a shock—he was a 50-year-old Chicago firefighter, and he died at the fire hall immediately after a fire. My first child wasn’t born until the next year. I can see a bit of my dad in the mirror, and in my kids, yet to this day I feel viscerally how crushing the permanence of death is.

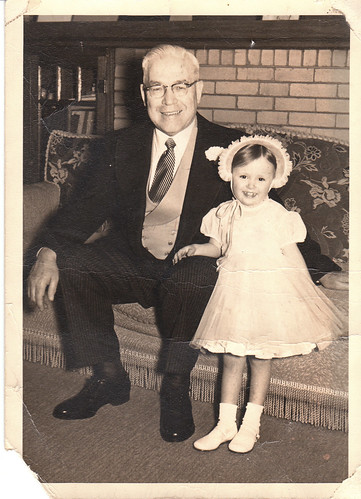

September 1 is the anniversary of another death, too—that of Martha, the very last Passenger Pigeon on earth. Martha died 37 years before I was born, but the profound sense of loss I feel for her came about long before I became a birder. I was sitting on my Grandpa’s lap—my father’s father—as he told me about how the skies used to be filled with beautiful pigeons until people killed every one of them. He’d never seen one, either. The year before he was born in 1896, the last recorded nest of a Passenger Pigeon was collected in Minneapolis, and he was only 4 when the last authenticated sighting of a wild Passenger Pigeon, in 1900 in Pike County, Ohio, was made by a boy with a BB gun. Despite large rewards for a living specimen, no more were ever again confirmed, dead or alive. So my Grandpa had no more memories of the species than I did, but he told me the stories his father and grandpa had told him, about the billions that once moved en masse through the country. My Grandpa read a newspaper story about Martha’s death when he was a teenager in 1914.

The concept of extinction was a difficult one for a preschooler to fathom, but my Grandpa’s profoundly sad look as he told me about this beautiful bird made me grieve, too. I saw at least one specimen of the long-lost species at Chicago’s Field Museum when I was taking college ornithology, and paid a lot more attention when I was teaching in Madison, Wisconsin. Several times I brought my middle-school students on field trips to the university zoology museum. The curator, Dr. Frank Iwen, always pulled Passenger Pigeons from the drawers for the kids to see. The birds were so beautiful, and his descriptions of the huge flocks and how people massacred them so vivid and gut-wrenching, that all the visceral feelings of sadness stirred by my Grandpa came flooding back, every time.

Frank then showed the kids specimens of declining species, and told us how critical it was for us to protect them so we wouldn’t one day be telling our children about reading in the paper about the death of the last Atlantic Puffin or Whooping Crane.

Today, two full generations after the Endangered Species Act was passed, a great many people have still not accepted this law of the land and are still trying to gut it rather than find legal ways to increase their personal wealth without compromising the wildlife that belongs to every one of us. The Supreme Court ruled in 1978 that "the plain intent of Congress in enacting" the Act "was to halt and reverse the trend toward species extinction, whatever the cost." Yet powerful moneyed interests would let dangerously declining species such as Lesser Prairie-Chickens and Greater Sage-Grouse go the way of the Passenger Pigeon, and people with no first-hand experience of these spectacular birds and no stories told by loving parents or grandparents have no visceral sense of what is at stake.

My feelings of loss with regard to the Passenger Pigeon are so deep because of my Grandpa’s stories, as his were because of the stories he heard by his own father and grandfather. There can be no more than one or two people still alive on earth who saw Martha alive in the zoo, and no human remains who saw with his or her own eyes flocks of Passenger Pigeons. As our society pulls ever further from the natural world, vulnerable species become little more than abstractions. When they vanish, who will be left to mourn them and tell stories about them?

My feelings of loss with regard to the Passenger Pigeon are so deep because of my Grandpa’s stories, as his were because of the stories he heard by his own father and grandfather. There can be no more than one or two people still alive on earth who saw Martha alive in the zoo, and no human remains who saw with his or her own eyes flocks of Passenger Pigeons. As our society pulls ever further from the natural world, vulnerable species become little more than abstractions. When they vanish, who will be left to mourn them and tell stories about them?

So on September 1 each year, I remember my father, and my Grandpa, and a bird that was once the most abundant bird on the planet but was killed off so long ago that none of us ever got to see one. On this hundred-year anniversary of the death of Martha, the last of her kind, I’m recommitting myself to fighting for the right to existence of the birds that remain, by trying to get more people out there seeing and connecting with real birds on this real planet, in the hopes that we will all be able to share living, breathing birds—the natural heritage of every American—with our children and grandchildren, not telling them stories of beautiful species that we sat back and allowed to vanish forever.