Part I: A relevant but tortuous history of my love affair with the Disney version of Sleeping Beauty.

In 1959, when I was seven years old, Walt Disney’s animated film Sleeping Beauty came out. My mother took us to see it at the Mercury Theater in Chicago. This was the first movie I ever saw in a theater, and everything about the experience filled me with joy.

I was familiar with the storyline of Sleeping Beauty before this. When I was very small, a family friend had read it to me from a big, ornate fairytale book, but that story seemed horrifying in every way. As in the Disney version, the evil fairy cursed the baby on her christening day: on her sixteenth birthday, the child would prick her finger on the spindle of a spinning wheel and die. But in that other version, the last good fairy didn’t make things better, at least not as far as I could see. She made it so Sleeping Beauty would sleep for a hundred years only to wake up when some strange prince came along and kissed her. What could possibly be good about that? Every single person she knew and loved would be long dead, including her dog. (Of course she’d have a dog!) And now she’d be stuck forever married to a creepy guy who had climbed into her bed to kiss her when she didn’t even know him, and he didn’t know her! To me, this seemed like a fate worse than death, and that was more than half a century before the #metoo movement. Even as a small child, years before Betty Friedan or Gloria Steinem spoke up about feminism, I hated that story.

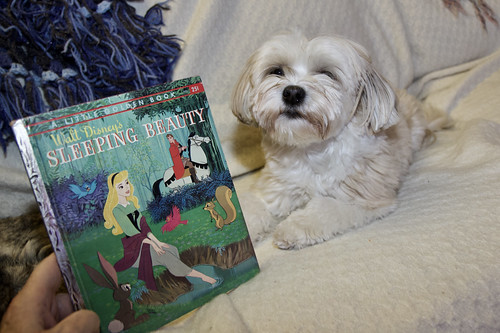

But then the Disney version came along. Before we went to see the movie, my Grandpa gave me the Little Golden Book version, and it was beautiful! Two of the fairies were named Flora and Fauna, words that I knew meant plants and animals (even though I thought the one named for plants should have been the one wearing the green dress). Sleeping Beauty’s real name was Aurora which, as the movie narrator said, means the dawn. In the woodcutter’s cottage in the forest, the fairies called her Briar Rose, which was equally lovely.

And that forest was so beautiful! As an adult, I realize how unnatural it was, but sixty years ago, the generic trees and flowers thrilled this urban child’s eyes. The book showed a blue bird alighting on Aurora’s hand and lots of animal friends, but didn’t show the charming way the rabbits, squirrel, owl, and songbirds worked together to give her a dream dance partner wearing the prince’s hat, cloak, and boots. That scene in the movies defies physics, biology, and natural history, but seemed wondrous to a seven-year-old; even today it’s impossible for me to see it without smiling. That woodland scene with the animals remains among my top ten scenes in any movie.

Aurora was no generic babe to Prince Philip—he fell in love with her beautiful, warm soprano voice and her charming interactions with the animals, whose love for her made it clear she was a kind and good person. And Philip was no generic Prince—Aurora didn’t even know he was a prince, just as he didn’t know she was a princess. He loved being out in the forest as much as she did, and he clearly loved his horse as much as she loved her forest animals. And Sampson the horse clearly loved Philip right back.

Sleeping Beauty is often touted as the epitome of a sexist fairy tale, the main female character asleep and powerless, needing a man to rescue her. That is definitely true of the original fairy tale, but Disney’s rendering rises far, far above that even while keeping the plot line that gives it the title. Sleeping Beauty may have been powerless to affect Maleficent’s curse, but the prince was equally powerless. The characters who controlled the outcome from start to finish were women—the three good fairies and Maleficent. The fairies rescued Philip from Maleficent’s dungeon, armed him, and ran interference every step of the way, magically turning the boulders dropped on Philip into bubbles, the arrows shot at him into flowers, the boiling oil poured on him into a rainbow, and Maleficent’s raven into a statue. The fairies untangled him when the forest of thorns snagged him, and at last enchanted and directed his sword straight into Maleficent’s dragon-heart. No, it wasn’t Prince Philip who rescued Aurora—it was the fairies. And the Prince did not kiss her because she was a pretty, generic woman in a bed, but because he and she already genuinely loved each other.

The movie ended, as Disney fairy tales are wont to, at a ball with the prince and princess dancing away, her wearing an insipid pastel Disney princess dress. But it was pretty clear they’d spend the days, months, and years of their future together in the forest. Maybe they’d even become birdwatchers!

Anyway, that was my perfect fantasy fairy tale as a child, not because of the ending but because of that glorious scene with the forest creatures. Disney never replayed the entire feature Sleeping Beauty on television during my childhood, though they did play a long excerpt on The Wonderful World of Color around when the movie was new. Disney didn’t re-release it in theaters until the summer of 1970, after my first year of college.

I talked Russ, now my husband but then my boyfriend, into going to see it at a Saturday afternoon matinee. That was when multiplexes were new, and the theater we went to was also showing Airport, the first big disaster blockbuster, starting at the same time, so there was a long line to get tickets. There were plenty of adults in line, but also lots of parents with small children—it was pretty clear which movie different people were headed for.

We got into line at the same moment that Wayne and Gloria, two of our good friends from high school, did. We hadn’t seen them in a year and were happy to catch up as we stood in line. But of course we knew that they were there to see Airport. As we got closer and closer to the ticket booth, Russ grew increasingly uncomfortable, clearly mortified about them finding out he was going to see Sleeping Beauty. I was so focused on his discomfort that I didn’t notice that Wayne was acting the same way. When we made it to the front of the line, Wayne said, “You first,” to Russ, and Russ said, “No—YOU first.” Sure enough, Wayne and Gloria had also come to see Sleeping Beauty—it apparently was the quintessential "chick flick." And it was just as wonderful as Gloria and I remembered. The next summer, a few months before we got married, Russ bought a 1971 Ford Pinto, which we named Sammy, for Sampson, Prince Philip’s horse.

Part II: Cut to the chase

As lovely as Disney’s Sleeping Beauty was for me, it was a treasure of childhood, not adulthood. Seeing the movie again may have been a momentary revisiting of that glorious childhood experience, but college and work experiences were filling me with new visions and dreams. I became a birder in 1975, and the real birds I could look at in my field guides and see in the flesh whenever I was outside easily and entirely displaced those generic Disney birds.

The only identifiable birds in Sleeping Beauty were Maleficent's raven (that came to such a tragic end) and the Great Horned Ow dancing with Briar Rose. I’ll never forget seeing my first real one, on January 15, 1976, in Baker Woodlot, the exact same forest where I’d seen my first chickadee less than a year before. It was the morning after a blizzard, some branches still topped with fresh snow, the frozen air not just bracing but biting. That was the winter when I discovered that trees moan and creak with cold—wonderful sounds I’d never paid attention to, or maybe even heard, before I started spending so much time outside searching for birds. Until I became a birder, as much as I loved being outdoors, my joy was diffuse and misty, like a baby cooing at colors and patterns before they resolve into specific objects.

It wasn’t until I started paying close attention to birds that I started noticing different habitats. Generic trees became birches, maples, aspen, spruce and pine. I’d never noticed how oaks cling to their leaves long after beech branches are stripped bare. These features and so much more, sharpening the generic into the specific, enhanced my appreciation of forests, giving them a richness I’d never even suspected, much less appreciated when Disney forests were all I knew.

It wasn’t until I started paying close attention to birds that I started noticing different habitats. Generic trees became birches, maples, aspen, spruce and pine. I’d never noticed how oaks cling to their leaves long after beech branches are stripped bare. These features and so much more, sharpening the generic into the specific, enhanced my appreciation of forests, giving them a richness I’d never even suspected, much less appreciated when Disney forests were all I knew.

On this morning, I was in my element, all my senses reveling in this real-life forest, and then there it was, that honest-to-goodness owl, looking down at me from a tall snag, so unspeakably beautiful, so unmistakable, so specific—not just a lifer, but a warm alive individual looking directly into my eyes—that I started to cry. I didn’t even think of Sleeping Beauty. Reality was too perfect and too consuming to conjure fantasy. That owl was magnificent, but it was no "Once Upon a Dream" bird.

But almost two years later, on December 3, 1977, a new lifer brought that wondrous fantasy of the Sleeping Beauty forest scene to life with a genuine once upon a dream experience.

By then, Russ and I were living in Madison, Wisconsin, in an apartment on University Avenue near Walnut Street. To get to my favorite birding spot, I had to walk down Walnut a few blocks, passing some university buildings and a huge commuter parking lot to reach the tree-lined walking path along University Bay Drive, which curved along the shoreline of Lake Mendota.

On this morning, as I was still passing the commuter lot, I started hearing an unfamiliar but pretty, whistled call note. Reflexively, I whistled back, continuing to walk toward the lake. The song had been coming from the northwest, meaning once I cleared the parking lot I’d have to turn left on the walking path to find the bird, but as I walked and whistled, the sound grew louder more quickly than I was walking—apparently, the bird was drawing closer to me as I drew closer to it. When I reached University Bay Drive, the sound seemed very close.

I whistled again, and suddenly, in flew my bird—robin-sized; soft gray back, breast, and sides; shiny black wings with white wing bars and flight-feather edging; the head a shade of russet I’d never seen except in my field guide. And picturing that, I knew this bird was a Pine Grosbeak—a lifer, Number 263 on my lifelist. I drank in the vision. Oddly enough, the bird seemed to be gazing at me in return.

I don’t know what compelled me to whistle again as I watched him, but I did, and the bird flitted a few branches closer and called back. I whistled again, and the bird drew even closer. Then for some inexplicable reason, I took off my left glove and reached out, whistled, and suddenly, just like that, the miracle happened. The bird alighted on my finger. Yep—exactly the way the little animated bird alighted on Sleeping Beauty’s extended hand, here I was, for one brief, shining moment, magically drawn into the most magical scene of the most magical Disney movie of my childhood. In my mind I could hear Mary Costa singing “I know you—I walked with you once upon a dream” even as I stood there, wide-awake, my heart so full I could hardly breathe much less break into song myself. The bird’s toes were icy cold with sharp little claws, his belly soft and warm against my finger.

Twice since then, kinglets have alighted on my hand momentarily, but not while looking into my face—I think they simply mistook my fingers for branches. Chickadees, nuthatches, and one Yellow-rumped Warbler have come to my hand for mealworms, a couple of Blue Jays have landed on me for peanuts, and when I was rehabbing, lots of baby birds I was taking care of have flown to me when I was teaching them to become wild. But never before or since has a truly wild bird alighted on me like this, neither for food nor as a mistake but simply because it wanted to be closer to me for a magical moment. I still don’t understand it.

Twice since then, kinglets have alighted on my hand momentarily, but not while looking into my face—I think they simply mistook my fingers for branches. Chickadees, nuthatches, and one Yellow-rumped Warbler have come to my hand for mealworms, a couple of Blue Jays have landed on me for peanuts, and when I was rehabbing, lots of baby birds I was taking care of have flown to me when I was teaching them to become wild. But never before or since has a truly wild bird alighted on me like this, neither for food nor as a mistake but simply because it wanted to be closer to me for a magical moment. I still don’t understand it.

Pine Grosbeaks are flocking birds that I seldom see alone. Usually when no other Pine Grosbeaks are about, lone individuals join robin or waxwing flocks, as if they'll come to any port in a storm. I wonder if this bird had been searching for other birds to associate with, so yearning for any connection at all that my whistling forged a temporary, magical bond.

However it happened, here I stood, this beautiful bird perched on my finger. I don’t know how long the moment lasted—it was one of those events when time really does seem to stand still, but it couldn’t have been too long because my fingers weren’t stiff, much less frostbitten, when at last the bird turned and flitted to a nearby shrub. He turned to face me one last time and I gave him one last whistle. He didn’t hurry away—just moseyed on, giving me time to come to my senses.

I’ve never been able to wrap my head around that experience. But that Pine Grosbeak, my real-life once-upon-a-dream bird, was surely my best bird EVER.

I’ve never been able to wrap my head around that experience. But that Pine Grosbeak, my real-life once-upon-a-dream bird, was surely my best bird EVER.