Part I: Why I don't normally enjoy reading books about epic adventures. You can cut to the chase and go straight to the review by clicking here.

I’ve often said that if I were to start a rock group, I’d probably be the only member, and I'd call myself the Pathological Moseyer. I’ve always been a plodding, lackadaisical sort of person, not the least bit inclined toward athletics or tests of physical prowess and endurance. Surprisingly, I was on a sports team once—as an undergrad, I was on Michigan State’s women’s fencing team. I loved fencing's precision and strategizing, and I could muster the necessary physical grace for foil fencing that I didn’t have for dance or anything else. I was skinny back then, providing a smaller target than most competitors, but my height was a handicap—being shorter than every woman on our college team and every woman I faced in competition meant I had to be quicker mentally to lure them close enough for me to touch before they realized they should have already touched me.

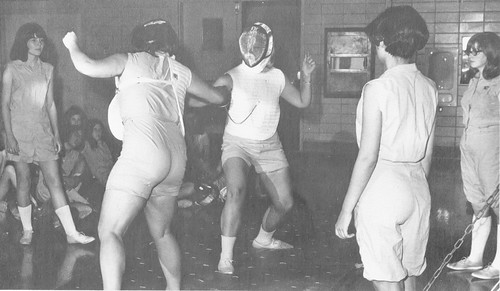

|

| The only photographic evidence of my fencing days, though this was from high school. I'm not one of the fencers here. I'm the scorekeeper standing closest but with my back to the camera. |

Since becoming a birder, the most physically taxing thing I’ve ever done was to ride my Schwinn 3-speed bicycle 60 miles from home to my in-laws’ place in Port Wing, Wisconsin one June day. I love biking, but again, it didn’t work as well as I expected. The soft purring of the gears when I coasted interfered with hearing Le Conte’s Sparrows, Sedge Wrens, and several warblers, meaning I kept coming to a complete stop to hear birds whether I was going past pastures or woods along Highway 13. It took over 6 hours to make it the 60 miles.

I’m a good if poky walker, but no one in my family likes to walk with me because I'm so slow. On family hikes, if the trail forms a loop, they invariably lap me, and even when they go around twice, they’re all done well before I get back from my first loop. I always see a lot more birds than they do, but even going faster, they notice plenty of things I miss. Their eyes and ears may not be as quickly receptive to the movements and sounds of birds, but unlike mine, their eyes and ears don’t filter out everything else

So except when leading a bird hike in Duluth or on a birding festival, or hiking on a birding tour, I usually hike by myself. The riskiest hike I ever did entirely alone was a 12-mile loop trail in Big Bend National Park in July 2013 to see a Colima Warbler. That hike took 10 1/2 hours, was entirely out of cell phone range, and was the only time in my entire life that I've come upon a mountain lion. When I had my heart attack two years later, a cardiologist told me about my congenital aneurism in a coronary artery and said that the heart attack could have happened at any time in my life, adding that if it had happened on this hike, "That would have been one happy mountain lion."

I have cross-country skis, but the shish-shish drives me crazy. I much prefer moving about on slow, quiet snowshoes. Even then, I’m a moseyer—If I’m snowshoeing with anyone else, I always bring up the rear.

Despite being poky and non-athletic, I do engage in some adventures that friends, including other birders, consider too risky, not even counting mountain lions. I’ve camped in a small tent or in my car, all alone or with a small, friendly dog, in lots of places over the years.

During my Big Year, I camped alone at Lake Umbagog State Park in Maine, the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge in Oklahoma, and Water Canyon Campground near Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge in New Mexico, as well as camping with my friend Eric Bowman at Yosemite that year.

On long road trips during my Big Year, I didn’t bring camping gear except my sleeping bag, an air mattress, and my pillow, depending on a supply of Fig Newtons when I didn't have a chance to shop for food, and I often slept in my car. People said they hoped that I at least kept the car locked all night and brought a gun, but no, I did the opposite. When I was a teenager, I was almost killed by a family member suffering from PTSD, and after talking him down with that gun pointed straight at me, there is no way I’ll ever own or travel with one, or allow one in my home. When camping, I always slept with my car windows open except when it rained—you can’t hear birds in a locked up car. The night I spent at Water Canyon I kept the hatchback of my Prius open all night. That’s where my head was, and all night long I dozed to the wonderful music of a Flammulated Owl.

Maybe because I’m not athletic and not particularly willing to take most kinds of physical risks, and am perfectly happy moseying through life, I’m not particularly drawn to fictional or true-life adventure tales. And I do very few book reviews on For the Birds—as much as I read and love books, I seldom go bonkers over them, and have never fallen in love with an adventure tale. So some people may find it strange that I’m devoting this entire week to a book about one adventure of the kind I'd never consider doing.

Part II: The Review.

Caroline Van Hemert’s The Sun Is a Compass: A 4,000 Mile Journey into the Alaskan Wilds is ever so much more than one woman's beautifully written account of a thrilling, dangerous, triumphant wilderness journey that she and her husband made in 2012, traveling from Bellingham, Washington, all the way up to the Arctic Ocean and across the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, just the two of them, with a few pre-planned drop-offs of food and supplies via the US Postal Service and Van Hemert’s parents.

The Prologue pulls us right into the story. She writes:

When we committed to this project—to travel from rainforest to ice-filled sea, from the edge of the continental United States to the edge of the earth—we decided it would be completely on our terms. No roads, no trails, and no motors. We would travel by foot, on skis, in rowboats, rafts, and canoes. We would use only our own muscles to carry us through some of the wildest places left on earth. This wasn’t a mandate borne purely of stubbornness, though Pat and I each possess a healthy dose of that trait, but because it would allow us to know the landscape as intimately as we knew each other. Just getting to remote places wasn’t the point. We could have hired a plane to drop us off at any number of locations that would qualify as the middle of nowhere. But we wanted something different. We wanted to hear the crunch of lichen beneath our feet, to smell the tundra after a rainstorm, to understand how it felt to walk in a caribou’s tracks or paddle alongside a beluga whale.

|

| Photos Copyright 2019 by Caroline Van Hemert and Patrick Farrell |

Caroline Van Hemert is a prominent ornithologist doing important work—I knew her name from her seminal research on deformed bills in Alaska’s chickadees—and so her weaving in birds throughout, especially chickadees, was certain to please my sensibilities. She has spent a lot of time in the laboratory, and a lot of time writing scientific papers, but despite providing plenty of enlightening information, her conversational yet lyrical, elegant prose would make all her references to birds and other wildlife enjoyable for even the most determinedly non-birding reader. Her encounters with two baby Rough-legged Hawks and a family of Brant geese were especially moving and lovely.

| |

|

| |

|

Caroline Van Hemert was kind enough to give me a nice long phone interview yesterday. I’ll be excerpting from it all week on For the Birds, and making the whole conversation available on a bonus podcast as soon as I can. The Sun Is a Compass will be released on March 19.