In the early 1990s, after I'd been a wildlife rehabber for several years, I started working on my ill-fated Ph.D. program, under one of my heroes, Dr. Gary Duke, founder of the Raptor Center. One old For the Birds program explains why I was puzzled about nighthawks, and how that led to my going back to grad school. Here's the updated transcript:

When most people ask me about birds, they first apologize, believing I'll think their questions are stupid. But the stupidest question I ever came up with turned out to have a pretty interesting answer.The day I got my first injured nighthawk to take care of, I discovered that he produced two completely different kinds of droppings. Most of the time, they were like normal bird droppings: brown fecal matter with white uric acid excreted from the kidneys. But once a day, he produced a yucky, smelly brown liquid that looked like diarrhea, which didn't jibe with anything I'd seen in other birds. I thought he had some sort of intestinal illness or injury, but after I'd cared for several nighthawks, I came to realize that the two different droppings types are typical of the species. I was curious about it, but somehow the issue of droppings didn't seem like a fitting topic for investigation.

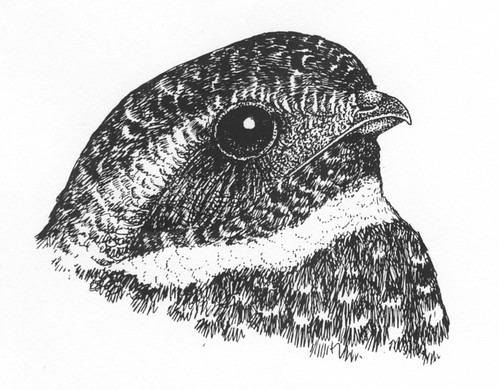

But the more I handled these handsome and gentle-spirited birds, the more I wanted to learn about them, and it slowly dawned on me that nobody else knew anything about their unique digestion either. Injured nighthawks that can't feed by catching insects on the wing are difficult for people to keep alive in captivity because they must be hand-fed, many times a day, so it was hard to find anyone who had observed what I saw. I wrote to one scientist who had raised nighthawks in captivity after learning that Poor-wills hibernate. Joe T. Marshall wanted to know if he could induce hibernation in nighthawks. When I asked him about their droppings, though, he said he never noticed, and suggested, accurately if a little oddly, that perhaps I noticed because I had children in diapers.Then I decided I was approaching the question from the wrong direction, and I started reading general ornithology textbook chapters about bird digestion. That's when I learned that "some" birds have structures called caeca. Just in case your memory of general biology is no better than mine, the caeca are a pair of intestinal offshoots branching out where the small intestine meets the large. In humans, the appendix occurs at the site of our caeca. Ostriches, chickens, Ruffed Grouse, and some other birds have very well-developed caeca. The descriptions of a chicken's caecal droppings matched exactly what I saw in my nighthawks.So what I first needed to confirm was whether nighthawks also have well-developed caeca, which seemed like the kind of basic question I could surely find an answer to somewhere. But none of my textbooks or reference works on birds, or specifically about nighthawks, had any itemization of whether they have caeca. Finally, I went to the UMD library and found a book by Beddard published in 1898, titled The Structure and Classification of Birds.It turns out that early ornithologists used the caeca as one of the primary pieces of evidence in establishing the taxonomic order of birds, much of which is still accepted today. This now-122-year-old book explained that the reason ornithologists originally concluded that owls aren't related to hawks and falcons is that owls have large caeca while other birds of prey have none at all.

Although I had an intuitive sense of the relationship of owls to nighthawks because of their excellent nocturnal vision and soft, pencilled plumage, it turns out that internally these two groups are even more similar, sharing virtually identical digestive systems. Some ornithologists believe that owls were originally insect eaters that eventually adapted to taking bigger prey. So wondering about nighthawk droppings ended up leading me to the explanation of why nighthawks are illustrated near owls in field guides (though in 2020, based on DNA, they are no longer considered quite as closely related), as well as giving me some insight into the work ornithologists were doing a hundred years ago.

After confirming that nighthawks do indeed have caeca, my next question became why? In Ruffed Grouse, the caeca grow huge in late fall and early winter, as the birds eat more and more aspen buds. Their smelly caecal droppings are the result of bacteria that produce an enzyme, cellulase, that breaks down the cellulose in woody tissue, allowing the grouse to get nutrition from their winter diet. As they switch to insects and softer foods in spring, the caeca atrophy.

The diet of nighthawks is 100 percent insect, without a speck of cellulose to be found, but suddenly I realized that nighthawks do eat something equally indigestible, in the hard wing covers of beetles—chitin. I wondered if in fact the bacteria in nighthawk caeca produce chitinase to break that down. So I called one of the world authorities on bird digestion, Gary Duke at the University of Minnesota, and asked him.

Gary hadn't thought about it at all, but got excited by my simply framing the question, and right there on the phone, he asked me to figure out the answer with him as his Ph.D. student. I was going to be his first Ph.D. student ever to do all my research without sacrificing a single bird—we'd work out ways of figuring it all out without hurting anyone.

I had to work slowly, because my children were still little. We pretty much confirmed my guess, but also that nighthawk caeca also serve an osmoregulation function, but I wasn't close to finishing before Gary developed early Alzheimer's disease. I was heartbroken losing him, but not so very sad about my Ph.D. All I really wanted anyway was the answer to my stupid question about smelly nighthawk droppings.