Of the thousands of bird songs in the world, if I were pressed to choose one favorite, I’m pretty sure it would be the Winter Wren's. This long, silver-threaded song is so exuberant and lovely that it fills me with joy whenever I hear it—it’s the sound I use for my cell phone’s ringtone and alarm clock. Somehow I can hear it from a couple of rooms away, but even in a restaurant or other public place, it doesn’t seem to annoy anyone. Outside, I can’t hear Winter Wrens as far away as I used to, but that gives me more incentive to wear my hearing aids when I’m birding.

When I started birding, the species that American ornithologists called the Winter Wren was the same as the one that European ornithologists simply called the Wren; that species also included the population found along America’s Pacific Slope up into Alaska, from which the Eurasian population originally reached Asia and Europe. Ornithologists have now split those two groups into separate species.

Intriguingly, the songs of both the Pacific and Eurasian Wrens include pretty much the same notes as our Winter Wren but sung at a much faster rate. Winter Wrens sing about 16 notes per second, which is darned fast, but Pacific Wrens sing more than twice as fast—a full 36 notes per second. Our human ears can’t resolve such rapidly delivered notes, making some of the tinkling notes into what we perceive as a buzz, and making the Pacific and Eurasian Wren’s songs less pleasing than the Winter Wren’s, at least to me. In his superb book, Birdsong for the Curious Naturalist, Don Kroodsma discusses these songs and provides, on the supporting website, recordings of the Winter Wren played at normal speed and slowed down and does the same with the Pacific Wren.

On the Fourth of July weekend, I went to Rib Mountain State Park in Wausau, Wisconsin. My main goal was to see a particular southeastern bird, the Acadian Flycatcher, whose range barely extends north into the park. I did not expect to find a bird I so associate with northern forests side by side with this southern bird. A combined map of the breeding ranges for both the Winter Wren and Acadian Flycatcher would pretty much cover the entire eastern half of the continent from the Gulf states and northern Florida all the way up to the Maritime Provinces and Hudson Bay, but there would be only a very thin line of overlap, which Rib Mountain happens to be within.

|

| Breeding range of the Acadian Flycatcher is shown in orange. The pale orange in northern Iowa, Wisconsin, and Michigan, the northernmost reaches of the range, indicates it's scarce there. Map from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology's splendid All About Birds website. |

|

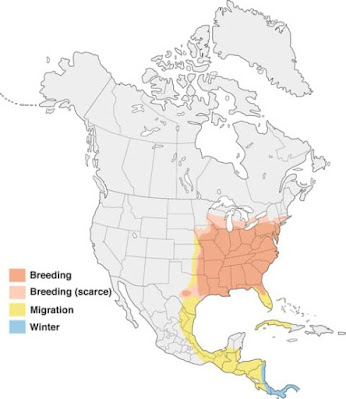

| Breeding range of the Winter Wren is shown in orange and purple, where they're found year-round. Notice that the main overlap between the two species is in the Appalachians, where the wrens are found at higher elevations, in conifers, than the flycatchers. Map from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology's splendid All About Birds website. |

Winter Wrens are mouselike in habits and appearance, being tiny and brown, and skulking about on the ground and low branches, usually trying to stay hidden in tangles. When they appear in backyards during migration, it’s often at a brush pile or raspberry patch or other bramble. In their breeding forests they may sing at any height—their voices carry farther from atop a tall tree, but I’ve seen them singing when barely off the ground. The one I watched singing at Rib Mountain spent a minute or two at my eye level, not a single branch blocking my view, which was so fun it drew my attention from the Acadian Flycatchers I was there to see.

I’d never thought about the likelihood of seeing both Winter Wrens and Acadian Flycatchers not just in the same general area but in the same woodland, both singing at the same time. Acadian Flycatchers need mature deciduous forests; Winter Wrens are found in evergreen forests near streams with lots of fallen logs and dense understories. How can they both find what they need in the exact same tiny area of one small park? I don’t know, but it’s pretty wonderful and cool that two such marvelous species do.