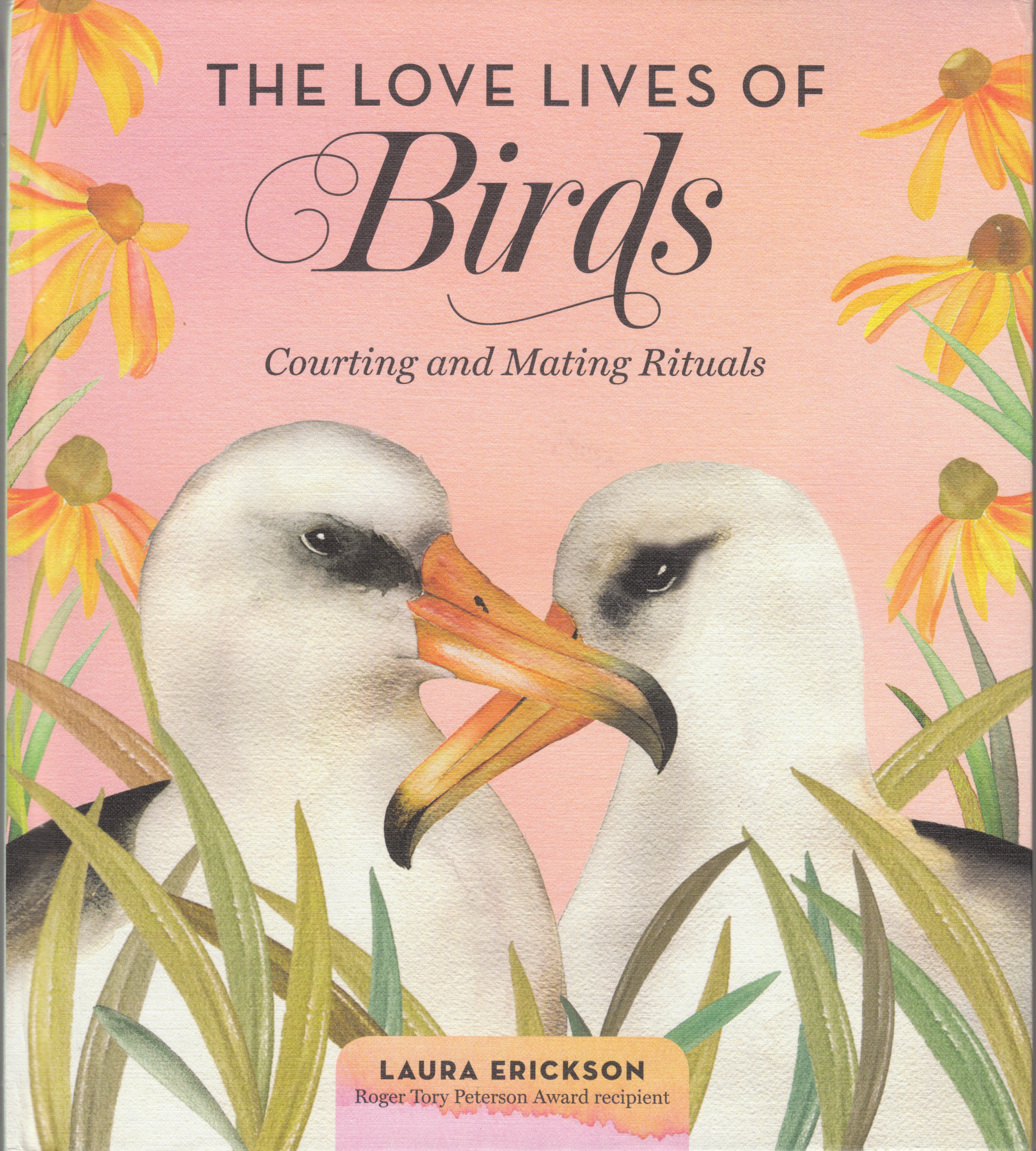

Last year, Storey published a book of mine, The Love Lives of Birds, in which we highlighted 35 species and their different approaches to acquiring a territory and mating.

Some species—swans, cranes, crows and many jays for example—famously mate for life and stay together throughout the year, whether they migrate away from their territory or not. Some, such as albatrosses, loons, and eagles, don’t maintain a year-round bond but return to the exact same territory each spring, ending up with the same mate year after year as long as that mate also returns.

Many songbirds commit to a mate for a single season, but the following year are as likely to settle in with another bird as that former mate. Some, such as House Wrens, stick with a mate to raise one batch of babies but then both birds very often find another mate if they want to produce subsequent broods that same season. Some forge a temporary bond for just part of the nesting cycle. For example, Mallard drakes stay with hens after courtship only through the time the females build nests and lay their large clutches of one egg a day for a couple of weeks. When a female starts incubating those eggs and loses interest in sex, her mate is out of there. Grouse, turkeys, woodcocks, and hummingbirds separate the act of mating from nesting and raising young; males mate with as many females as they can attract, forming no discernible pair bond with any of them.

There seem to be almost as many mating and territory strategies as there are bird species, and so covering just 35 species barely scratched the surface—that’s less than 5 percent of the more than 700 species that breed in North America, and less than a third of one percent of the roughly 10,000 bird species in the world. I could have written huge chapters about a lot of other birds, and particularly felt bad leaving out one fascinating species, the Acorn Woodpecker. Several researchers I know, including ones I worked with at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, focused years of research on this amazing bird.

I saw my first on Mt. Lemmon in Arizona on 7 April 1982 (no photos), and even before I got a glimpse of the birds themselves, I was gobsmacked by what they had done—one entire side of a log cabin where we stayed was riddled with hundreds, maybe thousands, of holes, virtually every one stuffed with a single acorn. I knew from my reading that Acorn Woodpeckers made these granaries, but had no idea they could be so huge, storing so very many acorns.

The granaries are constructed by family groups of a dozen or more individuals, who store the acorns communally, and cooperatively raise the young. Living up to their name and all the work involved in building, stuffing, and maintaining those granaries, Acorn Woodpeckers do eat a lot of acorns, especially in winter, but overall, their diet is surprisingly varied. They glean and dig out insects from trees as other woodpeckers do; catch flying insects on the wing; dig out sap wells to feed like sapsuckers; eat flower nectar; take small lizards, baby birds, and eggs; and eat some fruit and seeds. They also visit feeders for seeds, suet, and hummingbird nectar.

We know from decades of long-term studies of marked birds that Acorn Woodpeckers have an unusual mating system called opportunistic polygynandry. Within a group, 1–8 males compete for matings with 1–4 females who all lay their eggs in the same nest cavity. The males and females share incubating duties. In addition to these core breeding individuals can be 1–10 non-breeding “helpers” that assist the breeders in feeding nestlings. As with many other birds, such as crows and Florida Scrub-Jays, in which one or more individuals help nesting pairs raise their young, helpers at Acorn Woodpecker nests tend to be offspring fledged by the group in prior years. Non-breeding Acorn Woodpecker helpers may be as old as 5 years old. Cohorts of males and cohorts of females tend to be related to one another—usually siblings—but the two cohorts in a flock are not related to each other. Yep—that’s one heck of a unique mating system.

For many decades, long-term research projects studying birds like the Acorn Woodpecker involved marking individual banded birds with uniquely colored leg bands or wing tags and spending many hours in the field observing their activities. New high-tech equipment, from RFID tags to satellite transmitters of increasingly tinier sizes, are allowing researchers to get data on many more individual birds 24/7, even when no one on the research team is anywhere near. Newer, less expensive ways of testing DNA have taken the guesswork out of determining paternity and, in the case of Acorn Woodpeckers and other species in which multiple females share a nest, maternity as well. Now, thanks to two projects led by Sahas Barve of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, one published last year in Current Biology and another published last month in Proceedings of the Society B, we know a lot more about the Acorn Woodpeckers’ unique mating system, and also about how territorial battles between flocks attract non-participating Acorn Woodpecker as spectators.

It's long been assumed that for species in which the male and female parents both make fairly equal contributions to raising their young, monogamous pairs that defend a territory, not sharing resources with neighboring birds, are more successful than polygamous species in which males share their territory with other males. But the 2021 Smithsonian project found that that those male Acorn Woodpeckers that breed polygamously in duos or trios of males each fathered more offspring than males breeding alone with a single female. Females didn’t get the same benefit. Co-breeding duos of females produced the same number of offspring as the females that coupled up, but female trios left behind fewer offspring than either group.

Acorn Woodpeckers may provide an exceptional example of cooperation in their mate- and nest-sharing, but they have a violent, bloodthirsty, side, too, as research published last year by the same team led by Barve proved. A nesting group’s territory averages 15 acres with one or more granaries. Ownership is stable until there’s a death in the flock. If a breeding female dies, for example, coalitions of non-breeding “helper” females from other flocks will battle with the breeding and non-breeding females from the other flock, trying to take over from the homeowning females. Invading females may return day after day from their own territory. The term “battle” isn’t an exaggeration. Barve told a New York Times reporter, “We’ve seen birds with eyes gouged out, wings broken, bloody feathers and birds that fell to the ground fighting each other.”

Thanks to the RFID chips which tirelessly record birds every time they appear near the RFID reader, we know that some tagged individuals fought for 10 hours at a stretch for four consecutive days. Although a great many birds in the vicinity have been tagged, one long-lasting battle ended up being won by an unmarked coalition of females.

No one knows exactly how Acorn Woodpeckers get the word out, but soon after a death occurs, invaders arrive, and within an hour after the first blows, birds from other flocks arrive to watch. They may travel more than 2 miles and spend a full hour watching these battles. Spending so much time attending these battles just to observe must have some value—these birds would normally be spending those hours feeding young, searching out more acorns for their granaries, and defending their own territories to prevent the theft of acorns. Dr. Barve told the New York Times that studying other Acorn Woodpeckers must give them some sort of advantage. “They must immediately see all the big sibling coalitions in the area, gauge their body conditions and the quality of the territory they’re fighting over,” he said.

Working out the evolutionary advantages for watching other birds fighting is tricky, and we can’t help but wonder whether the impulse for Acorn Woodpeckers to observe other flocks engaging in these fights is comparable to the impulse of people to spend a significant amount of time observing football, World Wide Wrestling matches, or the crazier reality TV shows. But I guess it’s nice to know that there's a counterpart to spectator sports in the world of birds. Maybe there really is nothing new under the sun.