On November 6, 2021, my neighbor Jeanne Tonkin told me she'd just learned that a woman down the block, Jennifer, had a hummingbird coming to two feeders she’d left up all fall. Jennifer didn’t make a specific note of when the bird first appeared but knew it was before Halloween. I found out about it late in the day but went down and got photos.

The next morning Jeanne and I set out feeders in our yards, and within an hour, the bird was feeding at them, too. Since then, she’s been seen in my yard every single day through December 4, 2021, which is now the record late date for a Rufous Hummingbird in northern Minnesota.

Seeing a wild non-Ruby-throated Hummingbird in northern Minnesota at any time, much less so late in fall, is exceptional in every way, and people of course have questions. But that means that every time someone finds out about the one who visited my yard, I hear the same questions over and over. To simplify things for me, here are my answers to the most common questions:

Q. Is this the first time a hummingbird has appeared in Duluth in November or December?

A. Nope! Oddly enough, one appeared in my yard on November 16, 2004.

That one survived both a blizzard on December 2 and the temperature that night dropping to 6º F. I could hear my house creaking from the cold all night, and was petrified thinking about the tragic task I’d face in the morning, searching for a tiny carcass. But well before sunrise on December 3, she was back at my feeders. She spent the next two or three hours pigging out, and disappeared for good at some point between 9 and 10 am, an excellent time of day to start a serious migration flight. I kept my feeders up for a few days more, but she never returned.

The 2021 hummingbird visited my feeder quite a bit on December 4, a very mild day that got up to about 40º but with SSW headwinds. In mid-afternoon, winds died down and shifted to the northwest. A winter storm was approaching, and I believe she took advantage of the sudden new tailwinds and fuel from a full day's feeding on natural food as well as sugar water to light out ahead of the storm.

Q. How can a Ruby-throated Hummingbird survive a Duluth November, much less December?

A. It’s unlikely that a Ruby-throated Hummingbird could survive a late fall up here, much less a winter. But this bird is not a Ruby-throated Hummingbird. She’s a Rufous Hummingbird, a species that nests in Alaska, arriving before snow melts, and migrates through the Rocky Mountains.

Q. My field guide doesn't show Rufous Hummingbirds anywhere near Minnesota!

A. You’re right that field guides show only Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in Minnesota. The American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Minnesota (2016, second printing 2021) includes just one species of hummingbird, the Ruby-throat. But in the species entry, the author (me) writes:

Our only breeding hummingbird is common and widespread from Mother’s Day to Labor Day… Minnesota has records of six other hummingbird species, most in fall after Ruby-throats have left.

Here’s what the Cornell Lab of Ornithology's eBird says about fall hummingbirds in the East:

East of the Mississippi, it is well-known that there is only one expected hummingbird–the familiar Ruby-throated Hummingbird. Ruby-throateds typically arrive in April and the bulk have departed by the first of October. However, any hummingbird seen after about 15 October is more likely to be a rare western species than a Ruby-throated! The excitement of one of these western visitors prompts many people to keep their hummingbird feeders hanging until late fall, or even all the way through spring. The yield is high; some homeowners as far north as New Jersey and Massachusetts have had multiple appearances by rare hummingbirds. Try your luck and set out a feeder; below we discuss the possible species, give some tips on attracting late hummers, and discuss the identification of difficult species…

From October to January, Rufous Hummingbird is the most common species by far in the East, outnumbering other species by up to ten to one. This species, which may sometimes arrive on their breeding grounds in Alaska before the ice breaks, are particularly well adapted to cold weather. Females and immatures occur in the East with regularity from mid-October on, with arrivals peaking from mid-October to late November. Several individuals have wintered successfully as far north as Massachusetts, where one female (affectionately named “Rufy”) returned to successfully winter in a Bay State greenhouse for at least six years in a row (1996-2002). It appears that immatures that stray to the East and survive the winter are likely to return in the following year, and there are numerous records of banded birds reappearing in subsequent years. Several remarkable banded birds that have been captured in the Southeast and recovered near or on the breeding grounds (e.g., one Virginia Rufous was recovered in Montana, and was found back in Virginia the next winter!). Survivorship of such birds probably also account for increasing ratios of adults noted in the East.

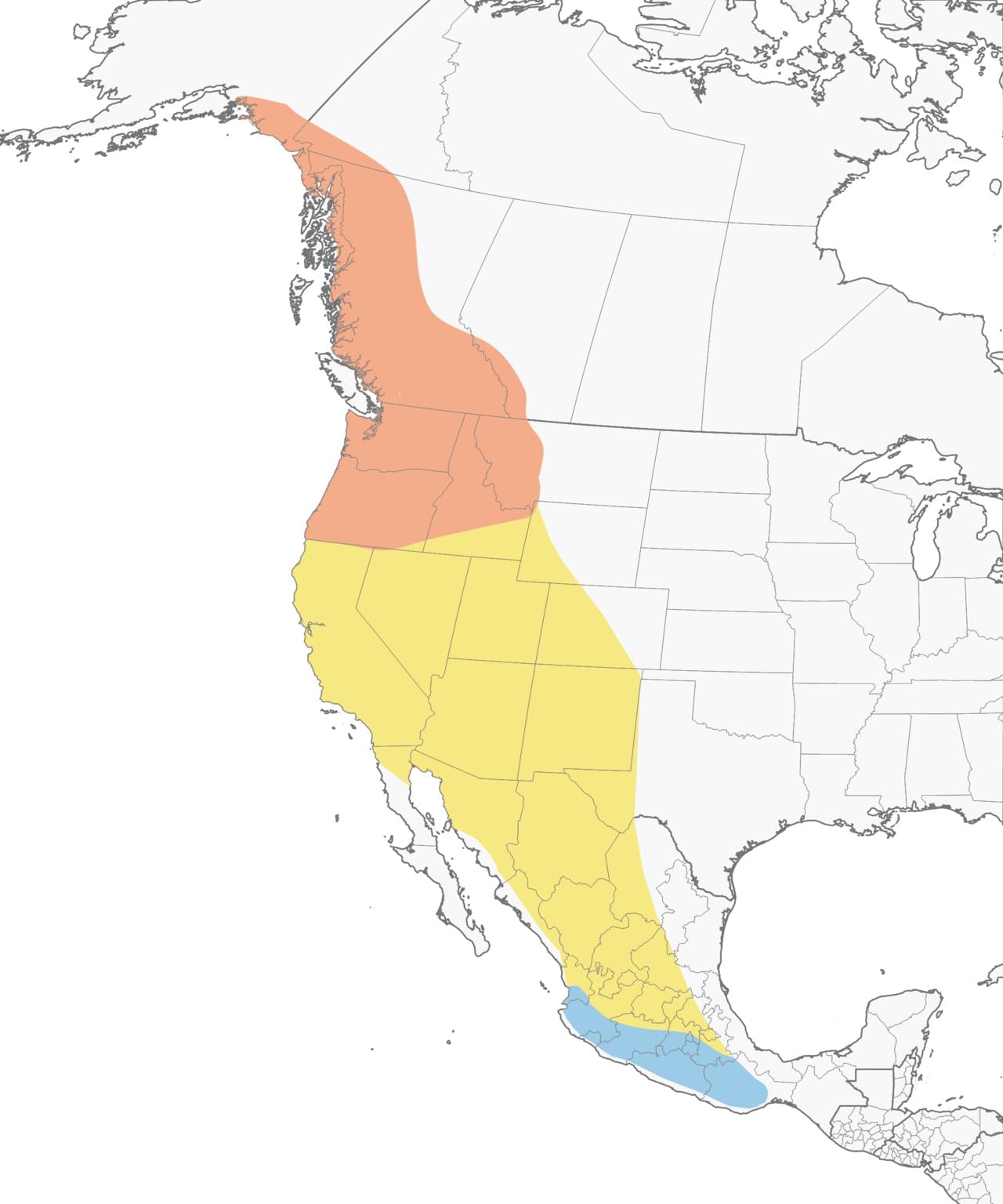

Here is Cornell’s range map for the Rufous Hummingbird:

But here is Cornell’s eBird map for Rufous Hummingbirds showing reports ONLY from November 2021. Apparently Rufous Hummingbirds are expanding their late fall/winter range.

Q. How can you be certain the 2021 hummingbird was an adult female Rufous Hummingbird?

A. Her orangey sides and tail confirmed that she was either an Allen's (Selasphorus sasin) or a Rufous (Selasphorus rufus) Hummingbird. Adult males of both those species are distinctive, with at least some rusty brown on the back.

|

| Adult male Rufous Hummingbird |

|

| Adult male Allen's Hummingbird |

Females and young males of both species have green backs (though the fluffy side feathers can sometimes show their rusty color behind the wings on the back when the feathers are lofted) and look extremely similar to each other. When we can’t see distinguishing markings or take careful measurements, we can’t be certain and must simply call the bird Selasphorus sp.

We knew this one was a female because the tips of the tail feathers were rounded and pure white—young males of both species usually have somewhat buffier tail feather tips—and because the flanks were green, not the least bit brownish.

And we knew this one was not a young female because there was so much flecking on her throat feathers; immature females have far fewer little spots, and usually lack the fairly large central spot.

So we knew she was an adult female, but how could we be sure she was a Rufous and not Allen’s? If she could be captured for banding, it would have been a simple matter to take measurements and closely examine the tail feathers, but no hummingbird banders were available to capture her, so we based identification on photos showing the subtle distinguishing marks.

Hummingbird tails have 10 feathers—five on the right and five on the left. Scientists call bird tail feathers rectrices (single rectrix) and they number them from the center feather out. R5 (the outermost retrix) is broader on a female Rufous than an Allen’s Hummingbird (this is subtle, but has been pretty evident), and R2 (the one next to the central feather) has a subtle indentation not found on Allen’s. Over the time she visited, we got several photos confirming that indentation on R2. Even though the indentation is there and seems to match the shape of R2 for female Rufous as depicted in Pyle's Identification Guide to North American Birds, Part I (often called the bird banders' guide), field guides seem to show the indentation on the proximal, not distal side as was the indentation on the feathers on my bird. So there may be more ambiguity on this than I originally thought.

Q. Based on the range maps, Allen’s Hummingbird should be incredibly rare in the Midwest. Why even consider that a possibility?

A. Although the vast majority of hummingbirds seen in November and December in the East are Rufous, once in a very rare while, an Allen’s Hummingbird does appear. In late November 2020, an Allen’s Hummingbird showed up at a feeder in New Glarus, Wisconsin, and remained through late December. That individual was banded to confirm its identity.

Q. How tiny is a Rufous Hummingbird?

A. Very tiny! Rufous Hummingbirds weigh 2–5 grams; the lightest are slightly lighter than an American dime (2.5 grams); the heaviest about the weight of an American nickel (5.0 grams). Ruby-throated Hummingbirds weigh 2–6 grams, and Black-capped Chickadees 9–14 grams.

Q. Is the chickadee the tiniest bird that would normally winter in northern Minnesota?

A. No. An even tinier insectivore that virtually never comes to feeders also regularly survives the extreme cold of northern Minnesota. The Golden-crowned Kinglet weighs 4–8 grams, its weight overlapping that of Rufous Hummingbirds.

The Brown Creeper, another insectivore that winters up here but virtually never visits feeders, just barely overlaps the hummingbird’s weight, tipping the scales at 5–10 grams.

Q. How can such tiny birds possibly survive late fall and early winter in the north?

A. Food is the most critical issue for any bird trying to survive here in winter. Bird feathers are like the highest quality home insulation, but even the best-insulated house will be pretty much the same temperature inside as out unless there is a source of heat to warm the inside—a fireplace, wood-burning stove, furnace, solar panels, etc. The source of heat in warm-blooded animals (mammals and birds) is their “metabolic furnace,” fueled by the food they eat.

During cold days, birds must eat a lot, and the smaller the bird, the more calories, or energy, it needs relative to its size. For its weight, sugar is very high in calories. Hummingbirds obviously capitalize on sugar-water feeders where they can find them, but even in winter they can get some sugars from sapsucker drill holes (though no sapsuckers remained in my neighborhood this winter to keep those drill holes fresh), and from tiny droplets of sap oozing from spruces and some other trees.

A hummingbird might be able to survive several days during a very frigid spell eating only at a feeder, but as soon as the temperature climbs into the teens, it must also find insects to get the protein and other nutrients it needs. When the temperature is below freezing, how can it possibly find cold-blooded insects? Its keen vision and hearing help it notice tiny winter-active insects such as springtails, and it knows from experience as well as instinct how to find tiny insect eggs and pupae hidden in crevices in all kinds of plants. The last day the 2021 hummingbird was at my house, December 4, the temperature stayed above freezing all day and reached 40º and there wasn’t any snow cover yet, though a major snowstorm was imminent. She spent a lot of time in the back of my yard where she could forage through goldenrod and other weedy plants that are excellent sources of insects, as well as a variety of trees and shrubs. A few of my neighbors (including Jeanne Tonkin) are native plant gardeners with a big variety of native plants that would also furnish tiny insects. On many of the colder days she was here, several birders, including me, watched her darting among branch tips of my spruce tree—that’s an insect-hunting behavior. So apparently there were lots of places for her to forage when she wasn't at our feeders.

Q. How do you keep sugar water from freezing?

A. Sugar water has a lower freezing temperature than tap water, not starting to ice up until temperatures are in the upper 20s. I brought my regular hummingbird feeders into the house overnight, setting them out about 6:45 am. On cold days, I kept twice as many feeders filled with fresh sugar water so I could swap room-temperature feeders for chilled ones whenever needed. Even when temperatures were in the 30s, I liked to swap them at midday and around 3 pm. As the temperature dropped to the mid- and lower-20s and even lower, I frequently swapped out the feeders throughout the day.

I also have two hummingbird feeders that are heated via a 7-watt lightbulb. They don’t keep the water warm but do keep it above freezing. The only place I know that sells these is Hummers Heated Delight, a little family-owned business in Two Harbors, Minnesota. (I went there the week of Thanksgiving and posted about them on my blog.)

Q. How can a hummingbird keep its body temperature up at night, the coldest time of the 24-hour cycle, if it can’t feed in the dark?

A. That's tricky! Duluth nights in early December are fifteen and a quarter hours long, and they get even longer until the solstice.

But believe it or not, in the same way that we can conserve energy by turning down our thermostat at night, many birds can turn down their body thermostats during sleep—this is called torpor. Just about all hummingbirds undergo torpor, but Rufous Hummingbirds have brought this to an exceptional level. Their daytime body temperature is about 102º F, but at night they can shut down their systems enough to let their body temperature drop to an astonishing 54º F! At first light as they awaken, they start shivering. That muscle activity raises their temperature so they can zip off with an urgent need to stoke up on calories ASAP.

Q. What’s the coldest temperature a hummingbird has survived?

A. Scott Weidensaul reports that in 2010-2011, Pennsylvania's first Anna's Hummingbird successfully overwintered in Berks County despite a week when nighttime lows dropped to at least -8º F. In January 2014, a banded Rufous Hummingbird near State College, Pennsylvania, survived air temperature lows of -9º F and wind chills of -36º F—the current record for any hummingbird. My 2004 hummingbird survived one night when temps dropped to 6ºF. The coldest night the 2021 bird faced, lows reached about 11º F.

Q. How long can a Rufous Hummingbird live?

A. One female Rufous Hummingbird banded as an adult in British Columbia in June 1996 was caught, alive and well, in British Columbia in May 2004, making her a minimum of 8 years 11 months (maybe a year or more older than that because her age was unknown when first banded) and she was still going strong.

Q. When there's a mild day, shouldn’t you take in your feeders so the bird will move on?

A. Any migratory bird stopping in an area during fall migration or winter makes its own day-to-day decisions about whether to stay or move on, weighing advantages and disadvantages and taking into consideration many issues we’re not aware of. Birds are also known to recognize signs of upcoming storms and cold fronts. Unlike non-migratory species, migratory birds DO tend to move on when the time seems right to them. But there can be real advantages to staying in a northern neighborhood as long as possible even as the temperature works its way down. How is that possible?

Because the 2021 hummingbird remained here over five weeks, she became very familiar with every inch of terrain. On nice days, she explored all around, figuring out which plants harbor insect eggs and pupae and which ooze tiny bits of sap. She knew which shrubs and trees offer the most food and protection from rain, snow, and strong winds from every direction. Having three different people in different locations watching her, we could see how her behavior patterns and preferred locations changed with weather.

She also became familiar with the local human and animal behavior patterns so could safely ignore many sounds and activities that would alarm her in an unfamiliar setting. Her familiarity with other birds in the neighborhood also gave her a heads up about danger and signals about when the coast was clear.

Taking away the feeders would have robbed her of the chance to leave when her body was most stoked up to cover a lot of miles. She would have been forced to move on or lose her most reliable source of calories, but before she left, she’d waste critical time and energy, burning essential calories, making certain those feeders really were gone. And how could we be certain that she could find a more favorable place that very day in time to get enough calories to get through another long winter’s night?

And how could a human decide that a particular day was the right one for a hummingbird to travel? The temperature in my yard on December 3, 2021 reached 41º F. That seemed like a good day to go, especially with a predicted snowstorm and cold snap just a few days away. But all day on the 3rd, there were steady, strong southerly winds, so the hummingbird would be flying into headwinds. The next day she took advantage of mild conditions all day to stoke up, and apparently was ready to move on in late afternoon, right when tail winds became favorable, even though all our feeders were still available.

Both the 2004 and 2021 hummingbirds were adult females who had already survived at least one and a half years, quite possibly more, and had successfully negotiated at least one previous fall migration and winter. They knew what they were doing. The adult female who visited me in November and December 2004 left at midmorning on December 3, after a blizzard and frigid night. That day highs were around 20. She, too, left with my feeders still in place.

Q. Shouldn’t you take mercy on a hummingbird and bring it indoors?

A. First, it’s illegal to “possess” a protected wild native bird, even temporarily, and even with the kindest of intentions. Even licensed rehabbers are prohibited from overwintering wild birds that had no actual injury or illness simply because people are afraid they’re out of range. Hummingbirds are wild animals with an inherent and legally recognized right to come and go where they want when they want.

If I had a greenhouse and the hummingbird could come and go as she pleased, I’d certainly keep access open for it, but I don’t.

And regardless, even when a hummingbird recognizes and apparently trusts a person, it doesn’t necessarily want to come indoors even during severe conditions. In 2004, during a blizzard, I set a couple of feeders inside my home office (there were feeders on the outside of those windows) and cranked the window open. The room was filled with houseplants, including many in bloom. Sure enough, the hummingbird flew right in to the center of the room near the ceiling, and hovered while making a 360º circle, seeming to study every inch of the room, and then immediately headed back out into the brutal blizzard. I kept the window open for several hours more, but her theme song seemed to be "Born (or Hatched) to Be Wild."

In the cases I know of when people captured out-of-range hummingbirds to "save" them (a Calliope Hummingbird in the Twin Cities one December and a Mexican Violetear in La Crosse, Wisconsin, one November), the birds died during capture and transport.

Q. It seems wrong to just let the poor thing die. When a hummingbird is found so late in the year, we need to do something!

A. When I moved to Duluth in 1981, Red-bellied Woodpeckers and Northern Cardinals didn’t range this far north. When an individual of either species wandered here, birders flocked to see it. Some of those early pioneer birds certainly ended up dying in severe winters, but no one ever suggested "rescuing" them or closing down feeders. Neither Red-bellied Woodpeckers nor cardinals undergo much torpor and are almost certainly not as hardy as Rufous Hummingbirds. Yet both these non-migratory species are now successfully surviving here year-round.

Some individual Rufous Hummingbirds have probably always wandered beyond what people believe their winter range is, but the numbers wintering in the eastern US are increasing every year, indicating that many of these birds are surviving to produce young likely to share the same migratory proclivities. These eastern pioneers may have an advantage over those wintering in Mexico who must deal with deforestation and other causes of habitat destruction, and weather extremes due to climate change. New generations of intrepid hummingbird explorers are proving far hardier and more resilient than anyone ever thought hummingbirds could be. I was not going to stop the two tiny adventurers who showed up in my neighborhood from doing what they wanted to do with their lives.

Q. If a hummingbird does end up dying from the cold, doesn't it suffer?

A. When most small birds, including hummingbirds, succumb to extreme cold, it’s either while they're fast asleep in the middle of the night, when air temperature is lowest, or as they emerge from torpor first thing in the morning, while still in a sleepy twilight state, if they don’t have enough energy to shiver. That doesn’t make their deaths any less sad and even tragic, but there are worse fates.

Q. I once had a late hummingbird in my yard, and a real expert gave me completely different advice.

A. What makes a person an “expert” is a combination of practical personal experience and having done research to find out what other people have learned. Every expert has biases, preferences, and experiences that influence how they interpret the same information.

The truth is, there is no "correct" approach to dealing with overwintering hummingbirds, and no “right” answers. We each struggle to reconcile the known facts with all the unknowns, making guesses about individual situations and what we think the birds want and what we think they need. We all hope for the best outcome—that each wintering hummingbird will survive to return to its breeding territory the next spring.

Q. Should I leave my own feeders up in late fall?

A. There is no avian internet or other communication network that tells birds “There’s a feeder on Peabody Street in Duluth, Minnesota!” The hummingbirds who discover a feeder had been flying over or foraging nearby when they first noticed it. It’s almost impossible for us to see these extremely unusual and inconspicuous birds unless we have a feeder up, and so scientists have a much easier time keeping track of late hummers the more feeders are out there. That's one of the reasons why the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s eBird team recommends that people leave their feeders up.

But if you do leave a feeder up, it will still be extremely rare for a hummingbird to materialize at it. Over the years, one or two immature Ruby-throated Hummingbirds have turned up at my feeder in early October. They didn’t linger—just took a long drink and moved on. I suspect these were late hatchings, finally in migratory condition and booking it south. The only times I’ve ever had a November “payoff” were in 2004 and 2021, a full 17 years apart.

So you probably will not get a hummingbird if you leave out feeders late in the season, but you definitely will not get a late hummingbird if you don't leave out feeders.

If you do leave out a feeder, you have a responsibility to keep the sugar water fresh. You don’t need to change it nearly as often in cold weather as you would in summer, but during warmish spells it still should be refreshed at least once a week, and every two to three weeks if the weather stays at refrigerator temperatures. If you do get a hummingbird, make sure to freshen the water right away and then start changing it much more frequently. It's also important during cold weather to monitor the feeder to make sure the sugar water doesn't freeze.

Q. What is the right recipe for sugar water?

A. Natural flower nectars vary in the concentration of sugars, from about 1:5 to about 1:3. In normal spring and summer conditions, the best recipe is the tried and true average—a quarter cup of sugar per cup of water. Hummingbirds need water to digest and metabolize sugar, so in hot, dry conditions, I sometimes make my sugar water a little lower in strength, about a fifth of a cup of sugar or a very scant quarter cup per cup of water. And during cold, wet springs, I often strengthen it to a third of a cup of sugar per cup of water.

During the very cold conditions a late or wintering hummingbird faces, it's perfectly fine to mix a third of a cup of sugar per cup of water. I also fill the center moat of my feeders with plain water, just in case a hummer (or more often chickadee) wants a simple drink. One snowy day in November 2021, I watched the hummingbird catching snowflakes with her tongue. Did she mistake the snowflakes for flying insects? Was she thirsty? Was she simply curious? I'll never know, because she wasn't talking.

Q. Why should I "report" a late hummingbird?

A. Reports help scientists work out answers to puzzles about why different hummingbird species turn up in the East; how they survive winters so much colder than they'd experience in Mexico, Central America, and South America; the nature of bird migration and seasonal movements; and more. Understanding these movements has important conservation implications, too, as we tease out whether hummingbird movements correlate with climate change in general and with changing local and regional patterns of droughts, flooding, excessive heat, fires, etc.

Q. I'm not a birder. How do I report a late hummingbird?

A. The simplest, most efficient and valuable way to submit a sighting is via eBird (www.ebird.org). Birders have come to trust this site, operated by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, but it does require you to register. For the report to be most useful, it should include your precise location, though for privacy, you can include just your city or general neighborhood.

Providing documentation is essential. Written descriptions are helpful, but photographic documentation is most important. Photos from a cell phone are better than nothing, but whatever your equipment, try to get clear photos showing the bird in flight and perched. Details of the tail feathers are especially important. After you report it, you will be contacted by an eBird reviewer to confirm your identification. If you didn't include your precise location, you can divulge more details to the reviewer, but be prepared for visitors. The reviewer will keep your location secret if you prefer.

If you are reluctant to use eBird, the next best thing is to find a local, trustworthy birder who will report the bird to your state ornithological society. That birder will probably also want to report the bird to eBird, but you can request the location to be left secret if you don't want birders visiting. If you don't know any birders, your nearest bird-feeding store should be able to point you in the right direction.

The BEST documentation of all would be to have a licensed hummingbird bander trap, band, and release the bird on a mild day.

Q. Do I really want to let a bunch of strangers know about my bird?

A. Please do consider letting the birding community share your hummingbird. My 2004 bird was a first county record for any Selasphorus and corresponded with a Great Gray Owl "invasion" that drew hundreds of birders from all over the country to Duluth, so a great many birders descended on Peabody Street to see the hummer as well. This bird was important to their life lists, state lists, and county lists, but equally important, it was thrilling for them to see such an exceptional little being. A hummingbird in northern Minnesota in November and December—imagine that! Every single one of them was polite and respectful of our neighbors' and our privacy and our dogs. Isn't such a rare and exciting event worth sharing? And a big advantage of letting birders come is to get confirming photos for identification.

If you allow birders to come see the bird, be clear about your expectations. My neighbors were very tolerant of strangers parking and walking about, but that wouldn’t work for many people. If you have concerns about birders disturbing your dog, leaving a gate open, blocking a driveway with their cars, etc., make sure to let the birding community know. The vast majority of birders will respect your rules. The many birders who came to see my 2004 and 2021 hummers were all extremely nice, respectful, and cooperative.

Q. Wouldn't it be harmful or stressful for a bander to capture my hummingbird?

A. Anything out of the ordinary can stress any bird, at least a little. The two out-of-season hummingbirds in my yard quickly got used to normal neighborhood activities, and I never observed any signs of stress or changes in behavior, especially after the first day or two, even when birders were close by taking photos.

But being trapped and handled are obviously more stressful than being gawked at or photographed. No ethical bander would trap any bird during inclement or terribly frigid weather. Even so, I would not consider allowing a bird bander without a special hummingbird permit to trap "my" hummingbird despite my knowledge about how important measurements and close-up photos are. Regular bird banders may have handled hummingbirds in the course of their everyday banding operations, but they do not have the experience with them to make the capture and handing quick, gentle, and efficient. As a former licensed wildlife rehabilitator who has handled many Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, I know how tricky it is to handle such a tiny creature, even in summer when my hands weren't cold and stiff. Also, regular bird banders seldom have the cage traps that are so much safer and less stressful for hummingbirds than mist nets. As mentioned above, the cases I know of where banders (NOT licensed hummingbird banders) caught a December Calliope Hummingbird and a Mexican Violetear, the birds died.

Also, only licensed hummingbird banders have the proper sized bands for hummingbirds. Birds captured by anyone else, including other banders, would go through all the trauma of being captured and handled without even being banded!

But I have been very open to having an experienced hummingbird bander come to trap and band my hummingbirds, both in 2004 and 2021. Unfortunately, licensed hummingbird banders are few and far between, and none were able to come to Duluth while the hummers were here.

Q. If you leave a tiny hummingbird out there in the cold, can you guarantee that it will survive?

A. No. Nor can I guarantee that any one of my individual chickadees or Blue Jays will be alive tomorrow, or even an hour from now. The natural world is filled with danger, yet every living creature is the outcome of millions of years of evolution. Rufous Hummingbirds are the genetic result of a long line of the fittest Rufous Hummingbirds surviving and reproducing. A great many hummingbirds are now wintering in the East, many of them repeats, so some must be crossing northern Minnesota at some point. All the evidence points to the likelihood that both the hummingbirds that visited my yard were migrating "properly," and knew the right time to migrate on.

I would have been heartbroken if either had been here at the very end of a cold day followed by a frigid night, and then didn't appear the next morning. But I would have been consoled by the fact that this adult, experienced bird had lived her life on her own terms and died in her sleep rather than at the hands of a well-meaning person who thought they knew more than she did.

As remarkable and fun as it was hosting such exceptional birds, the not knowing what would happen to them from day to day, keeping up with scary weather reports, and dealing with criticism and questions from people unfamiliar with new patterns of western hummingbird movements and just how hardy these tiny birds actually are became very stressful for me. But I took consolation in a lovely poem, "Not Knowing," by John O'Donohue from his book, No Man's Land. It is very worth reading.

I am endlessly relieved that in both cases, the little hummingbird visiting me through early December disappeared when there was a perfect window of opportunity to move on.