|

| White-throated Sparrow |

I’ve always had an affinity for sparrows, starting with the House Sparrows that cheeped outside my window when I was a very small child, telling one another about their day’s adventures.

|

| House Sparrow |

I could never have dreamed that the ancestors of these confiding, cheerful little creatures had been ripped from their native lands in Europe and Asia and released in ecosystems here that weren’t prepared for them, leading to so much death and destruction to bluebirds, Purple Martins, and other American birds.

|

| House Sparrow |

When I became a birder, I was shocked in reading my first field guides to learn that American ornithologists didn’t consider them sparrows at all—both the Golden and Peterson guides said House Sparrows belonged to a family called “weaver finches.” Current taxonomists have taken them out of that family, putting them into a smaller family of “Old World sparrows.” That’s fitting—the English word sparrow had been used for centuries in reference to the Eurasian and African birds called by that name in even the oldest English translations of the Bible. If taxonomists were at all consistent in applying nomenclature rules, they’d have come up with a different name for our American sparrows. That which we call an American sparrow by any other name would be as sweet.

|

| House Sparrow |

|

| White-throated Sparrow |

Be that as it may, I remember the exact moment when I fell in love with my first all-American sparrow, on April 12, 1975. My favorite instructor at Michigan State University, Bob Hinkle, had brought a group of us graduate students to a naturalists’ conference in Natural Bridge, Virginia. We were gathered near the conference center when I heard the most strikingly beautiful bird song imaginable—a pure, whistled song. Bob Hinkle said it was a White-throated Sparrow singing Old Sam Peabody, Peabody, Peabody. I had to see the bird to count it on my life list, and so Bob led me to the hedge where the song was coming from, and voila!

|

| White-throated Sparrow |

Much as I’d always loved House Sparrows, the bold black, white, and yellow markings on my lifer White-throated Sparrow’s head were as striking and memorable as its song. Two weeks later, back in Lansing, when I saw some at the feeders in the Fenner Arboretum, I didn’t need a field guide to identify them. The next year we were in Chicago for a bit during spring migration and there they were, right in Russ’s parents’ backyard in the very neighborhood where I’d grown up, singing away. How had I never once noticed that amazing song, so very easy to hear now that I was aware of it, during any of the 23 springs of my life before I took up birding? I often wonder how many other beautiful things right there in my own world today don’t exist for me because my eyes and ears filter them out of ignorance.

|

| White-throated Sparrow |

A lot of people growing up in urban, suburban, or rural areas learn their first sparrows as I did. The Old-World House Sparrows may be woven into the fabric of their daily lives, whether they’re hearing them out their bedroom window or tossing French fries to them at fast food restaurants. And the next sparrow to grab their attention is very often a White-throat singing that pure, whistled song or showing off its striking markings, the spark prompting many people to reach for a field guide for the very first time.

|

| White-throated Sparrow |

Half of all White-throated Sparrows don’t have the bold black-and-white head pattern but, rather, a much duller, tan-and-off-black pattern. The marking between eye and bill is usually much more brilliant yellow in the white-striped than the tan-striped birds, and the white throat on these duller birds isn’t as bold and clearly defined, either.

When I started birding, I assumed the birds with duller plumage were females, and half of them are, but so are half of the boldly striped birds. All the white-striped birds, male and female both, sing, but only male tan-striped birds sing. That’s an interesting story in itself, but because migrating tan-striped birds are found in the same flocks as white-striped birds, identifying them is almost as straightforward as identifying the more boldly marked White-throated Sparrows.

|

| White-throated Sparrow |

|

| White-crowned Sparrow |

One other sparrow has similar black-and-white striping on the head: the White-crowned Sparrow. Its body shape is different, but you need to spend time with both species before that feature is helpful. More useful are the White-crowned Sparrow’s pink or yellowish bill rather than the nondescript dark bill of the White-throat and the fact that White-crowned Sparrows don’t have any sign of a yellow lore.

|

| White-crowned Sparrow |

The White-throated Sparrow has an overall warm, brownish appearance while the White-crowned has a solid gray underside and a cool gray nape. The White-crowned Sparrow’s throat feathers may be whitish, but they don’t have a border setting off the White-throated Sparrow’s defining feature. Once in a rare while, a White-crowned Sparrow spends winter up here, but every one of them breeds far from here. White-throated Sparrows nest in the woods all around us, including small woodlots in towns and cities up here, so are fairly easy to find all summer. A handful of them may also spend the winter in the Northland.

|

| White-crowned Sparrow |

*****************************

|

| American Tree Sparrow |

Four sparrows that may visit our feeders in spring have rusty or rufous caps. (I have to specify spring because immature White-crowned Sparrows have a rusty cap when we see them in fall.) The American Tree Sparrow, one of the first to arrive at our feeders in April and who overwinters not too far south of my neck of the woods, has a rufous line matching the crown color, which starts at the eye and widens in the cheek area.

|

| American Tree Sparrow |

The tree sparrow’s upper bill is dark but the lower is bright yellow. From most angles, you may see a “tie tack”—a spot of dark feathers in the center of the clean gray breast. The American Tree Sparrow usually also has a small soft brown or rufous patch on either side of the breast at the bend of the closed wing.

|

| American Tree Sparrow |

|

| Chipping Sparrow |

Most tree sparrows vanish right as Chipping Sparrows arrive. Both species have conspicuous rusty caps, so a lot of people confuse them. Chippie bodies are shaped a little different, but that isn’t helpful until you’re familiar with both. Chipping Sparrows have a clean black eyeline that starts at the bill, making it look as if they were wearing eyeliner. Spring adults have a solid black bill. The Chippie’s underside is a pale shade of gray close to off-white, it lacks the Tree Sparrow’s tie tack, and it never has a rufous patch at the bend of the wing on the side of the breast.

|

| Chipping Sparrow |

|

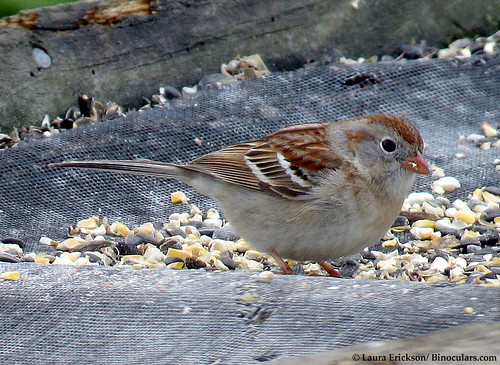

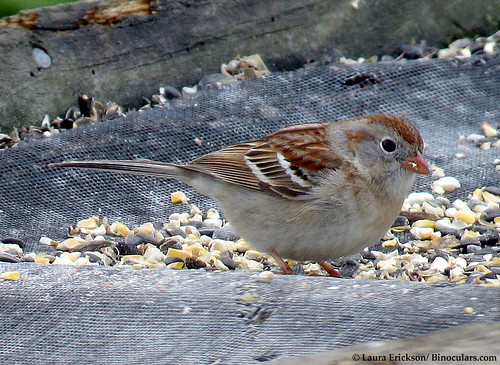

| Field Sparrow |

Field Sparrows are hardly ever seen as far north as Duluth but are common nesters not too far south of here and should be working their way north with the warming climate. They don’t have any eyeline at all which, along with their pale eye-ring and pink bill, gives them something of an anemic look. They have a small rufous patch behind the ear where the tree sparrow’s eyeline broadens. And the Field Sparrow has a simply gorgeous, easy-to-learn song: a sweet slurred note repeated, faster and faster.

|

| Field Sparrow |

|

| Swamp Sparrow |

The other sparrow with a rusty cap is the Swamp Sparrow, which doesn’t show up at feeders often and the cap is much darker. The wings and tail also have a lot of that dark chestnut color. The Swamp Sparrow’s breast can appear slightly streaked.

|

| Swamp Sparrow |

|

| Clay-colored Sparrow |

Even though my backyard is entirely the wrong habitat, a Clay-colored Sparrow or two often shows up here during spring migration. This is a small, fairly pale sparrow with a line starting at the eye and widening at the cheek. That line is darker than that of the American Tree Sparrow but not as clean and distinctive as the eyeline of the Chipping Sparrow. It does have a light gray eyebrow line, not as distinct as the white eyebrow of the Chippy, and a soft brownish cheek patch bordered above by that eyeline and below by an equally dark line. Outside of spring, Chipping Sparrows can also have a cheek patch but never bordered with a dark line below.

|

| Clay-colored Sparrow |

The first thing I notice on a Clay-colored Sparrow is the soft gray nape, which stands out because of the brownish cheek patch. Winter Chipping Sparrows share that nape and cheek patch color, so to be certain, make sure you see the lower border to the cheek patch.

|

| Clay-colored Sparrow |

|

| Harris's Sparrow |

The last sparrow likely to turn up in northland backyards is the largest and, perhaps, the coolest of all, Harris’s Sparrow. In spring it’s unmistakable, with a very black crown and bib, gray cheeks with a small black marking behind the ear, pure white underside, and pink bill. Both adults and immatures look entirely different in fall, but not at all like other sparrows except, due to the black bib, a little bit like House Sparrows. Which brings us full circle.

|

| Harris's Sparrow |

|

| House Sparrow |