In 1870, back when Ulysses S. Grant was president (I mention this only to give a bit of historical context and because Grant was my favorite president, though neither that fact nor Grant himself have any bearing on this), a shipment of European songbirds imported from Germany arrived in St. Louis, Missouri, part of a widespread effort to introduce birds from other continents to North America. Most of the released birds didn’t survive long in this unfamiliar land. Some individuals managed to mate, and some pairs lived long enough to breed, but for virtually all the species brought here like this, any descendants died out within a few generations.

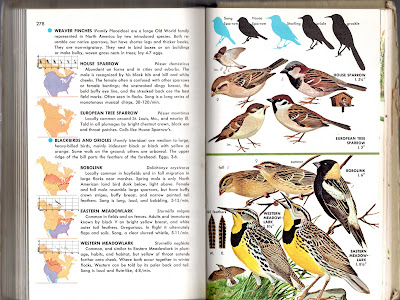

But individuals of one species in that St. Louis release not only survived and bred successfully but gradually become established: the Eurasian Tree Sparrow. Both that species and its close relative the House Sparrow were introduced in many places throughout the continent during the nineteenth century. The House Sparrow spread like wildfire, but the only introduction of the Eurasian Tree Sparrow that “took” was this one. For over a century, the species stayed within a narrow range in northeastern Missouri, west-central Illinois, and southeastern Iowa.

It's probably just a coincidence that the U.S. range of Eurasian Tree Sparrows coincides fairly well with that of fans of the St. Louis Cardinals. The baseball team didn’t exist until 1881, and was called the St. Louis Browns until 1900, so the bird was established well before the St. Louis Cardinals even existed, but if these little immigrants had any interest in baseball, they’d of course root for the red birds. (I suppose it's also a coincidence that Ulysses S. Grant lived in St. Louis for a time, too, though that was before the Eurasian Tree Sparrows were brought there.)

I learned about Eurasian Tree Sparrows four years before I became a birder, when my University of Illinois biology class took a field trip to the St. Louis Zoo in 1971. My professor optimistically thought they’d be hopping around the zoo grounds with House Sparrows, but he could not pick one out. I wasn’t quite clear what he was talking about until I became a birder and read my Peterson and Golden Guides cover to cover. Russ and I stopped in St. Louis on our way to Texas in December 1978, and we spent Christmas morning walking cluelessly around a few neighborhoods without luck.

Little by little over the next quarter century, I saw most of the birds in my field guide. By 1999, my life list reached the magic number I’d set as a goal when I started out: 600 species. Now when I thumbed through my field guide, the birds I had not seen stood out glaringly. So on the morning of October 28, 2004, I made it to St. Louis, where a guy on the national Bird Chat listserv had invited me to see it at his feeder.

I’m not the kind of person who senses auras, but on this morning as I entered St. Louis on the expressway, the entire city seemed weighted down with a palpable gloom. It was creepy, but I could not explain it, especially because I was so filled with joyful anticipation of seeing this longed for lifer.

I reached my friend’s house a few minutes after his flock of Eurasian Tree Sparrows had left for a while. As we waited for them to return, we mostly chatted about the upcoming election (Ulysses S. Grant was not running), but then switched to sports and the World Series. (As a Cubs fan, I hardly ever had reason to notice the post season.) The night before, the Curse of the Bambino had ended, and Boston was celebrating their first World Series win since 1918. Suddenly I realized the oppressive melancholy in the air was real, this morning after the Cardinals’ heartbreaking loss right there in St. Louis.

We stopped talking about sports when the Eurasian Tree Sparrows returned to his feeder.

In 2006, I became fast friends with a wonderful woman named Susan Eaton who lives in St. Louis. I’ve stayed with her several times and have never once missed the sparrow.

During my Big Year in 2013, I wasn’t able to stop in St. Louis except for a brief stop on the way home from Texas in July, when I was in a big hurry. Even the most reliable feeder birds come and go, so to improve my chances, Susan’s husband David spray-painted a sign, “ETS for Laura.” And the moment I stepped into their backyard, voila!

In 2014, I saw and photographed the sparrows where they actually belong, in Austria and Hungary.

In January 2015, I saw a few in Quincy, Illinois.

Even though their range here in America is so restricted, Eurasian Tree Sparrows have popped up in at least 10 states and 3 provinces. (The New Jersey record is assumed to be ship assisted, as are the several different west coast appearances, particularly multiple records on Long Beach, California, which is a major port.) I’d never seen one outside its normal range despite some appearances in Wisconsin and Minnesota, until 2017, when one turned up in Two Harbors. A great many birders saw it, virtually always perched in trees right at the Do North Pizzeria.

Two Harbors is in Lake County, and I figured that was as close to home as I was ever going to see this bird. But this week, one turned up at Scott Wolff's bird feeder right here in Duluth on Park Point.

The coolest thing about that, of course, is that we’re in St. Louis County. I don’t know if this individual was hatched in that other St. Louis County or came from parents in Iowa, Illinois, or somewhere else. I like to think this little bird traveled from one St. Louis County to another, like the saw-whet owl Frank Nicoletti banded at Hawk Ridge who was recaptured at a banding station in that other St. Louis County, coincidentally when my friend Susan was helping.

I love how birds crisscross the continent and the world, stitching connections between people and places as they enrich our lives.