A long, long time ago—at least 11,000 years ago—many people were already living in the shadows of the highest mountain in North America. The Athabaskan people called it Denali, which means “the high one,” and that’s the name Native Alaskans, most other people who grew up in in Alaska, and mountaineers called it throughout historical time, before and after a presumptuous prospector named William Dickey, who came up to Alaska in 1896 from Seattle and stayed there only a year, took it on himself to rename the mountain. President William McKinley had never been to Alaska in his life and had even less connection to the territory than Dickey, but McKinley supported the longstanding gold standard at a time when his chief rival, William Jennings Bryan, was supporting a new silver standard. It’s understandable that a literal gold digger would try to suck up to the most politically powerful man in the country, but harder to understand how he had any say in changing the name of a mountain that already had a perfectly good name.

But politics does weird things. A United States Geological Survey report in 1900 refers to "the giant mountain variously known to Americans as Mount Allen, Mount McKinley, or Bulshaia [a corruption of the Russian name for it before they sold Alaska to the United States].” The author apparently had no clue about the actual longstanding name of the mountain, and throughout the rest of the report called it Mount McKinley. McKinley was a popular president, and his assassination in 1901 made many people hungry for a permanent memorial to him, though it seems odd they’d settle on a mountain he had never seen, 4,000 miles from his native Ohio. A 1911 USGS report, The Mount McKinley Region, Alaska, kept that inappropriate and unofficial name alive, and Congress made it official in 1917.

Even more peculiarly, in 1965, Lyndon Johnson declared the north and south peaks of the mountain the “Churchill Peaks,” again to honor someone who had never visited Alaska.

In 1975, the Alaska Legislature asked the federal government to officially restore the mountain’s name as Denali. But Ohio’s congressional delegation managed to block this year after year until 2015, when the Obama administration announced that the name would be changed to Denali in all federal documents. All the Republican members of Ohio’s congressional delegation complained. During his 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump promised Ohioans that he’d change the name back to McKinley, but after the election, Alaska’s two Republican senators, Lisa Murkowski and Dan Sullivan, asked him not to.

That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet, and all the nomenclatural bickering in the world cannot chip away at Denali’s stature as both the highest and tallest mountain in North America. Denali is not higher than Mount Everest, whose summit is 29,032 feet above sea level—Denali’s is only 20,310 feet—but it is taller than Everest measured from top to bottom—Everest rises from the Tibetan Plateau, between 13,800 and 17,100 feet above sea level; Denali from a plain just 980 to 2,950 feet above sea level. Denali is not even the tallest mountain in the United States—it’s dwarfed by Hawaii’s Mauna Kea, which may only reach 13,803 feet above sea level but rises out of the ocean floor, 19,700 feet below sea level.

By any measure, Denali is ginormous, but our Alaska birding group didn’t see it at all when we drove from Anchorage to Denali National Park on June 18, nor while we were doing our wildlife tour of the park on June 19. The mountain was right there, of course, but enveloped, as it usually is, in clouds, many of its own making.

Oddly enough, Russ and I actually did see Denali’s peak on June 12 when we weren’t expecting it at all, from the airplane when we were flying from Anchorage to Nome. The mountaintop was sticking out above the dense cloud cover when I happened to look out the window and alerted Russ.

Our whole birding group lucked out on June 20 when we drove back to Anchorage from Denali. The clouds started breaking up in the morning, and we could see at least part of Denali’s snow-covered peak from a couple of birding spots.

Traveling up from Anchorage on June 18 and back down again on the 20th, we made a lunch stop at Mary’s McKinley View Lodge, a wonderful restaurant which not only serves delicious lunches but also has the most scrumptious brownies I’ve ever eaten.

Going up to Denali, I didn’t at all mind not being able to see the mountain from the cafe—I was too busy in the parking lot photographing Violet-green Swallows.

This splendid swallow belongs to the same genus as our familiar Tree Swallow but is daintier and even quicker on the wing. I got to spend a lot of time with Violet-green Swallows when Russ and I took our kids to Yellowstone back in 1995, but that was before I was photographing birds. I saw them in Colorado during my 2013 Big Year but wasn’t close to where they were nesting so couldn’t get a single photo—they dart about much too quickly for me to photograph in flight. But there were several Violet-green Swallow nests at Mary’s McKinley View Lodge, and a few of the birds perched cooperatively in full view of my camera.

Coming back, the swallows were busier with nesting. I did get a few more photos of them, but this time spent more time pointing my camera at Denali.

The mountain itself is certainly spectacular, but so is the wildlife of the area. On the drive up on June 18, we got to watch a mother moose with twin calves at Trapper Creek along the George Parks Highway. We were far enough away, on the opposite side, that I didn’t expect her to take umbrage at us, but she kept looking our way while leading her babies away. The photos I took of her were my favorite moose pictures of the trip.

The next day, we took the Denali National Park Tundra Wilderness Tour—a 5 ½ hour narrated bus tour through the park. Our guide was knowledgeable about birds, but other than our group, most of the people on the full bus were not focused on birds, and so we spent most of our time looking at mammals. There were moose of course...

and some distant Dall’s sheep...

but I was most taken with my very first looks at wild alive caribou, or reindeer. Some of them even provided decent photo ops.

This bus was larger than the vans our group was traveling in, and we mostly had to stay in it when we stopped to look at animals, but the bus had the huge advantage of windows that open, so my photos from the bus were much better than the ones I took from our vans. The other mammal I got to photograph that day, through the wide open window, was an extremely cooperative Arctic ground squirrel.

We also got decent looks at a Golden Eagle and several Northern Harriers. Our final photo-op of the bus tour was of a stunning male Willow Ptarmigan dust-bathing in the gravel road.

He moseyed to the side of the road as we watched, and my window was perfect for getting my best photos ever of Alaska’s state bird.

Some of us took a short after-dinner optional trip on the Denali Road that same day in hopes of seeing a Northern Hawk Owl. Sure enough, we got great looks and nice if distant photos of one being harassed by a pair of Varied Thrushes and a feisty little Ruby-crowned Kinglet.

My favorite photos of the evening were of a much more abundant species, a pair of Semipalmated Plovers nesting right on the gravel road.

We returned to the same spot the next morning, June 20, for those same birds before heading back to Anchorage. On that drive, we also saw one last Arctic Warbler.

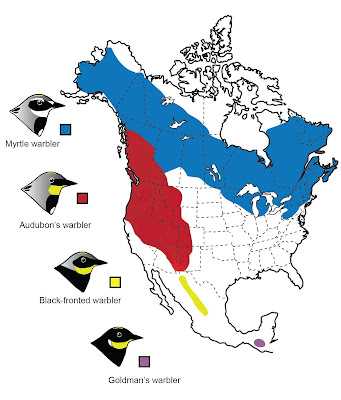

I didn’t add any lifers on the entire Denali part of our trip. Indeed, a lot of the birds were species I get to see regularly in the Sax-Zim Bog or even in Duluth, such as Lesser Yellowlegs, Northern Hawk Owl, Common Raven, Canada Jay, Boreal Chickadee, and Yellow-rumped and Blackpoll Warblers. Interestingly, the subspecies of Yellow-rumps we were seeing was the Myrtle Warbler, the one we see here in the East, whose breeding range stretches from the Northeast all the way across the continent to the Northwest.

The Western subspecies, Audubon’s Warbler, is found in the West, but not as far north as Alaska.

I didn’t at all mind the lack of lifers around Denali; as much as I like to keep my life list up to date and add to it, the greatest pleasure of birding for me is, simply, seeing birds and other cool wildlife. And by any measure, a lot of the birds we saw were thrilling, no matter how many times I may have already seen them.

|

| Lesser Yellowlegs |

|

| Common Raven |

|

| Boreal Chickadee |

|

| White-crowned Sparrow |

|

| Blackpoll Warbler |

Of all our national parks, Denali has experienced the highest, scariest temperature increases due to climate change. Some of the direr predictions claimed that the mean annual temperature at the Eielson Visitor Center, at mile 66 on the Denali Highway, would rise to 29.8ºF by 2040, but it’s risen much faster, the mean annual temperature averaging 32.4ºF in 2015–2019.

The Tundra Wilderness Tour used to be a full-day trip covering the entire 92 miles of the Park Road. Long stretches of the road are built on what were once stable rock glaciers. But those glaciers are crumbling as the ice within them melts. Last July and August, road crews had to spread up to 100 truckloads of gravel per week to fill in the slumping road, until adding gravel was no longer tenable. On August 24, 2021, they closed the road for the rest of the season. The road has continued to crumble until it's now completely impassable, so this season it never opened beyond mile 45. The Eielson Visitor Center is closed until further notice.

Our species is supposed to be the smartest one on earth, but what good is intelligence when so many people refuse to listen to scientists? I am bewildered and furious that to this day the United States is treating climate change as a partisan issue rather than the urgent problem it is.

Alaska is a unique and priceless national treasure, with species found nowhere else in the country and in some cases on the continent. Some of these are incredibly charismatic animals that people especially love, such as puffins, polar bears, and reindeer. Americans of all political stripes worked together to pass the Endangered Species Act in 1973. Where is that universal political will when we need it more urgently than ever?

|

| She's looking at us as if she knows her babies' survival depends on us. |