Every one of the 118 works in this year’s “Birds in Art” exhibit at the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum in Wausau, Wisconsin, deserves in-depth coverage, but that would take a whole book, and there already is one—this year's exhibit catalogue. I have to cover at least a few, though I'm leaving out others just as splendid.

Swiss-born Lucrezia Bieler produces exquisite papercuts using a single sheet of black paper cut with small, sharp scissors and mounted on white matboard. Her “Woodcock” depicts a female on the nest as a central image surrounded by a circular frame of 18 adult birds and two almost-hidden tiny chicks. The museum also enlarged that piece to display over an entryway. At the artist's original scale or much huger, the art was gorgeous.

Another impossibly intricate work is Corinne McAuley’s “Mallard Duck,” in which she painstakingly stitched 22,000 tiny glass beads, one at a time, row by row, passing needle and thread through each bead twice to hold the rows together in a stunning tapestry capturing the brilliant iridescence of a drake Mallard’s head.

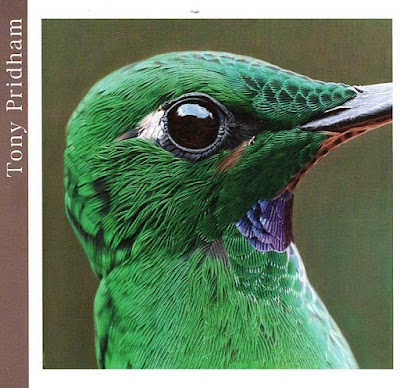

Australia’s Tony Pridham created a hyperrealistic four-foot square oil on linen of an Ecuadorian hummingbird called the Green-crowned Brilliant. It’s shown 300 times life size, each feather and the reflection in the bird’s eye exquisitely detailed.

I was thrilled to see a painting by one of my real-life friends, Kenn Kaufman, whose splendid portrait of an Amazon Kingfisher on oil on ampersand gessobord is titled “Emerald Amazon.” The kingfisher is perched in a cecropia among huge leaves dwarfing the bird in size if not in stunning presence.

The only artist to have had a work selected in every one of the 47 Birds in Art exhibits since its inception in 1976 is Guy Coheleach. His oil on canvas of Tundra Swans is titled “Flight of Four.” He writes, “When these birds are in flight, their necks have a rhythm that is almost wavelike, as they come close to one another and separate. The swans in Flight of Four are meant to evoke that feeling.”

Gary Staab’s “The Last Stand” is a bronze sculpture of a Dodo. Staab wrote that he was “interested in a pose with more motion than other recreations.” He succeeded brilliantly. The dodo’s extinction in 1662 has always seemed tragic to me on an intellectual level, but looking at this life-sized, three dimensional sculpture, the bird’s tiny vestigial wings lifted winsomely as it seems to run, wild-alive, gave me a visceral sense of loss I’ve never felt before, even looking at excellent dodo artwork.

Some works are impressionistic and minimalist, like Shelley K. Breitzmann’s acrylic on canvas, “Room to Breathe.” Breitzmann lives not far from Duluth, in Foxboro, Wisconsin. Her artist’s note explains, “On a day of thick fog, I startled a great blue heron from an estuary on the south shore of Lake Superior. Rather than retreating, the heron flew over the lake toward open water, disappearing into the fog.” The distant heron, recognizable only by the shape and curve of the wings, is shown in what Breitzmann called the “otherworldly instant just before the bird disappeared.”

The works in the catalog are alphabetized by the artists’ last names, so it wasn’t intentional to have Breitzmann’s painting in the book face another monochromatic work capturing a single moment just before something happens. Belgium’s Carl Brenders produced a pencil on illustration board of a Northern Saw-whet Owl titled, “Eyes on the Prize,” which wasn’t the least bit impressionistic but, rather, almost photographic in detail. His notes explain that the subject was a tame bird kept by a rehabber, but in his piece, the bird is sitting on a lichen-covered branch, looking at a specific point somewhere below and to the right of the frame, the intensity of its gaze and stance capturing the split second before it pounces.

Many of the works in “Birds in Art” are less about the natural world than about the intersections between birds and humans. Every year I’m thrilled anew at how different artists in the “Birds in Art” exhibit interpret the subject. When I entered the first exhibit room, the very first thing to catch my eye was the Netherlands’ Marcel Witte’s imposing acrylic on Belgian linen titled “Multicultural,” depicting 40 identical rectangular birdhouse fronts, 31 inhabited by different birds from all over, from budgies to a Cuban Tody. Witte was inspired by Thomas More’s novel, Utopia. He writes,

My metropolis is a multicultural society, with birds from many countries and with individual tonalities. It is an idealized image in which everyone lives together in harmony, with space for individuals and personal touch. Is this a utopian dream?

S.V. Medaris created a reduction linocut on Magnani Pescia paper titled “The Last Mark,” a moving memorial to her little dog Dexter making his last mark as vultures fly above. Medaris writes,

The composition is a zigzag, showing Dexter the way—away from the vultures and the suffering of his last days…At the vanishing point, it zigs up into the clouds and zags up and out of the frame: safe passage for Dexter away from the buzzards and the earthly realm.

Robert Martin’s lovely acrylic and oil on canvas and slip-cast porcelain on oak shelf is titled, “Jacket Portrait (Martin Ross) with Red-winged Blackbird Pair,” produced as a tribute to his uncle and namesake, who died due to complications with HIV the year the artist was born. The displaying redwings on the shelf were artifacts from his uncle’s life, and his exquisite portrait depicts a golden sky behind his uncle, looking to the right, the same direction a large flock of silhouetted redwings behind him are flying.

Some of the pieces are steeped in whimsy and good humor. Scot A. Weir’s “Whiskey Row” is a hyperrealistic oil on Ampersand gessobord depicting a Common Raven coming down to an ice cream cone spilled on the ground. (It reminded me a bit of an episode in Season 5 of Better Call Saul, only there are no ants here.)

Sigríður Huld Ingvarsdóttir’s watercolor on Arches paper, “City Scavenger” shows a Hooded Crow on a garbage receptacle in Berlin.

Elaine Twiss’s striking and whimsical “Wake Up!”, an acrylic on Arches paper, is a surrealistic painting of a vintage alarm clock and a wind-up toy bird squawking.

David Milton’s hyperrealistic paintings have captured my attention since I first started going to the exhibit decades ago. This year, his watercolor and pastel on Arches paper, titled “Blue Swallow Motel,” shows a motel he stayed in on Route 66 in Tucumcari, New Mexico, the motel restored and preserved in 1940s style with a gorgeous bird motif on the neon sign.

Rebecca Korth’s stunning still life oil on gessoed hardboard, titled “Swallow Clementines” depicts oranges in a glass and on a table, a Tree Swallow perched on one. The magnificently glowing plumage of the bird in the original took my breath away.

Michael Santini’s “Empathy” is an oil on linen board depicting a stylized Great Egret, the tip of its dangling elongated tail holding a bell, an elvish character grasping an egg with one hand while hanging onto the middle of the egret’s tail like a life line,. Santini writes that the painting “conveys our desires, actions, and motives for helping others in need. In celebration, the bell at the end of the bird’s tail calls attention to the renewal and restoration of nature.”

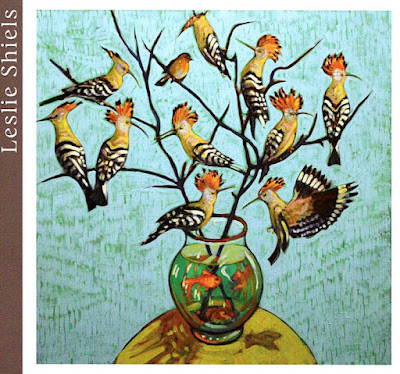

Leslie Shiels’s oil on canvas, “Hoopoes, Robin, and a Goldfish,” appears almost whimsical on the surface but has a deeper, more somber meaning. Reflecting on the war in Ukraine, she wrote,

Each and every time a news source shows bombs, flames, and devastation, I think of the innocent wild creatures that are victims of this conflict among men. The hoopoe is one of them. Their world is shrinking. We live in a fish bowl. The little European robin, ubiquitous in western Europe, bears witness. The innocents in nature are birds.

So many wonderful artworks fill my mind and heart, making the four-hour drive home fly by. I could write whole pages about every piece in this year’s “Birds in Art” exhibit, and feel bad that I couldn't cover more of it here. Admission to the Woodson Art Museum is always free, and it’s open every day except Mondays and holidays. “Birds in Art” will remain on exhibit through Sunday, November 27 and, after closing, will travel to New York, Iowa, and Kansas. I can’t recommend it more highly.