|

| Black-tailed (front) and Bar-tailed Godwits Illustration from Naumann, Natural history of the birds of central Europe, 3rd Ed. 1905 |

When Russ and I arrived in Nome on June 12 this year, the very first bird I added to my life list, at the mouth of the Nome River, was a wonderful one, the Bar-tailed Godwit. There are four species of godwits in the world, and this one completed my godwit list.

Godwits are large shorebirds with straight or slightly upswept, extremely long bills, which they use to probe deeply in sand and soft mud for aquatic worms and mollusks. In winter, they flock together where food is plentiful.

The English word godwit was first recorded in about 1416–17. Its origin is uncertain—it may have been an imitation of the bird's call, or it may have been derived from the Old English god whit or god whita, meaning “good creature”, probably suggesting good eating. Sir Thomas Browne, writing in about 1682, noted that godwits “were accounted the daintiest dish in England.” English speaking people would have encountered both Bar-tailed and Black-tailed Godwits, though they probably didn't worry about telling them apart. Linnaeus didn't distinguish between the two.

The Black-tailed Godwit, the national bird of the Netherlands, breeds from Iceland through Europe and areas of Central Asia, and winters in the Indian subcontinent, Australia, New Zealand, western Europe, and west Africa. I saw some in June 2015 when I was in Austria and Hungary but didn’t get any photos. In November 2016, I saw some wintering in Uganda and got distant photos during a boat trip.

The Bar-tailed Godwit breeds further north, on Arctic coasts and tundra from Scandinavia east to Alaska. The Bar-tailed Godwit includes five different subspecies with different breeding and wintering ranges and migration routes.

|

| Maps by Onioram |

When creating the first scientific names, Linnaeus placed the godwits in the same genus with several long-billed sandpipers. He considered both the Bar-tailed and Black-tailed Godwits the same species, and in 1758 gave them the scientific name Scolopax limosa; Scolopax was the Latin word for snipe and woodcocks, and limosa was Latin for “muddy.” Two years later, French zoologist Mathurin Jacques Brisson decided that the godwits deserved their own genus, Limosa and re-named the Black-tailed Godwit Limosa limosa and the Bar-tailed Godwit Limosa lapponica.

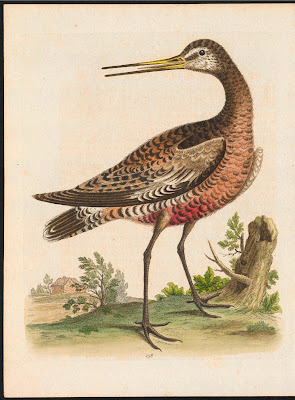

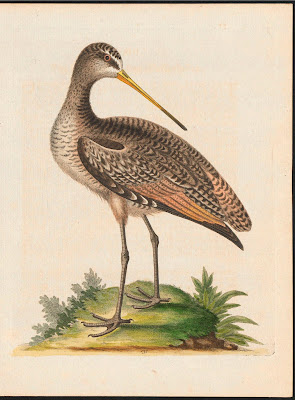

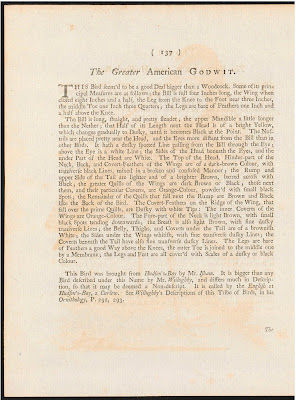

We’d expect to see only two godwits in the Lower 48: the Hudsonian Godwit and Marbled Godwit. The English naturalist George Edwards described and illustrated both of these species in his 1750 work, A Natural History of Uncommon Birds. Edwards called the Hudsonian Godwit the “Red-breasted Godwit”...

... and the Marbled Godwit the “Great American Godwit.”

Edwards based those illustrations and information on specimens brought to London by James Isham following a Hudson Bay expedition. Linnaeus referred to George Edwards’s work when he included both species in the 10th edition of his Systema Naturae.

Hudsonian Godwits breed in the far north near the tree line in Alaska and northwestern Canada and, as the name suggests, on the shores of Hudson Bay; they winter in South America. In good weather, they can make the south-bound journey non-stop, which explains why most of my sightings of Hudsonian Godwits in Wisconsin and Minnesota have been in spring, including my lifer, which I saw in May 1977 at Goose Pond near Madison, Wisconsin. I also saw them in Kansas in April 2015. I would have missed the Hudsonian Godwit altogether in my 2013 Big Year except that I lucked into two of them at the Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge in Upstate New York on September 28.

My photos are horrible, but it was a very lucky sighting—during migration, most East Coast sightings are from late July through early August, not the very end of September.

This June, I saw two Hudsonian Godwits in breeding plumage at the Westchester Lagoon in Anchorage, Alaska.

The Marbled Godwit, the largest of the four godwits, breeds in mid-continental North America, eastern Canada, and the Alaska Peninsula. The largest winter ranges are along the Atlantic, Pacific and Gulf coasts of the US and Mexico. I saw my first Marbled Godwits in September 1978 at Goose Pond. Since then, I’ve seen them many times in many places in Minnesota, California, Texas, Colorado, and Kansas.

So by 2014 I’d seen 75 percent of all the godwit species in the world. But the one I hadn’t yet seen, the Bar-tailed Godwit, was the one I was most fascinated by. Next time I’ll explain how this extraordinary bird made it into the Guinness Book of World Records.