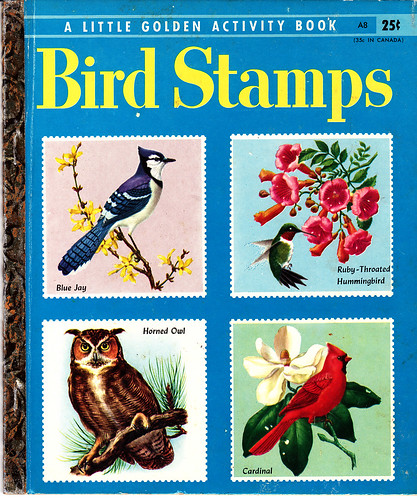

When I was four years old, my Grandpa gave me my very first book: Bird Stamps: A Little Golden Activity Book, originally published in 1949. Being rather precocious, I’d already memorized the entire entry about birds in our family encyclopedia, but that encyclopedia was in black and white. So was my new stamp book, but it came with 18 big, full-color stamps to stick on the pages. I pored over the entries, reading the simple descriptions of each species and imagining a world where a person might actually see a Bluebird, a Baltimore Oriole, a Hummingbird, a Red-Wing, a Red-Headed Woodpecker, or a Horned Owl in real life. (I'm using the spellings used in the book here.)

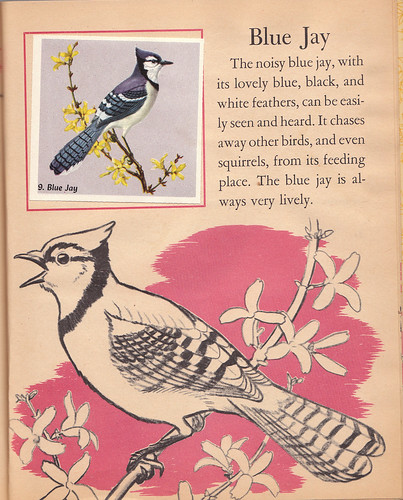

Bird Stamps included the only three species I knew personally from my own neighborhood: the Robin, Cardinal, and House Sparrow. The other 15 were nowhere to be seen in Northlake, the blue-collar suburb of Chicago where I lived, at least as far as I could tell. So for the most part, this was a book of tantalizing mysteries. When my family went to Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, when I was 5, I saw a Blue Jay, which I recognized from the book, and I was thrilled. I wondered if there were 14 other places where I could go to see the remaining ones.

I left my Bird Stamp book on the swing set when I went in for my nap one day, and it rained that afternoon. We weren’t the kind of family who knew how to deal with this sort of damage, when the book was still at least somewhat salvageable, so although I could picture some of those 18 birds in my mind’s eye, my precious book was gone forever. Fifteen or so years later when I started birding, I couldn’t remember all the birds in the book, so didn’t know exactly when I finally saw all 18 species pictured in the book, but thanks to the miracle of the Internet and eBay, now I do.

During my first spring of birding, spent in Lansing, Michigan and home in Chicago, I saw 10 of the 18 species: the Robin, Baltimore Oriole, Cardinal, House Sparrow, Blue Jay, Red-Wing, Red-Headed Woodpecker, Starling, Ring-Necked Pheasant, and Mallard. When summer rolled around, I took a field ornithology class in southern Michigan and added six more: the Meadowlark, Bobolink, Barn Swallow, Belted Kingfisher, Ruby-Throated Hummingbird, and Bluebird. The sheer richness of those first months of discovery, seeing 78 species for my lifelist between March 2 and the end of June, kept me in an almost constant state of euphoria.

By year’s end, I’d seen 17 of the Bird Stamp species (adding Herring Gull in northern Wisconsin that fall), and on January 15, I added the last one, the Horned Owl. Appropriately, that was in Baker Woodlot on the Michigan State campus, the same place where I’d added my first bird, the Black-capped Chickadee (a species not in Bird Stamps), just 10 months earlier.

In today’s digital world, children have access to a far richer wealth of full color and video images of just about anything in the world than I could have imagined in the 1950s. That rich source of information is a wonderful treasure, but I often worry about how drab real life might seem in comparison. My father-in-law used to tease me that he could see birds way closer up, doing more interesting things, by sitting in his living room watching Marty Stauffer, than I could by going out birding. He didn’t really believe that, but I wonder how many children would rather look at Internet videos of pandas and polar bears, usually produced in zoos, than of real-life meadowlarks and bobolinks made in the wild? So much of the artwork of today adds a fake layer of cuteness and drama to real-life images of birds, setting up weirdly false expectations about nature. And even as the virtual world expands, the real world grows increasingly diminished: today some of the species in my golden book are far rarer than they were when I was a child.

|

| Baltimore Oriole Population Trend, 1966–2013 (Breeding Bird Survey data) |

|

| Barn Swallow Population Trend, 1966–2013 (Breeding Bird Survey data) |

|

| Bobolink Population Trend, 1966–2013 (Breeding Bird Survey data) |

|

| Red-headed Woodpecker Population Trend, 1966–2013 (Breeding Bird Survey data) |

|

| Eastern Meadowlark Population Trend, 1966–2013 (Breeding Bird Survey data) |

Nostalgia about my childhood makes the reality of the 1950s rather rose-tinted. On windy days, the sky was dotted with puffy blobs of soapsuds churned up where our polluted creek gushed through a dam. The DDT truck ran through our neighborhood on summer nights. I did actually see a Baltimore Oriole once in my yard, but it was dead, the morning after one of those sprayings. This was hardly an idyllic world to reminisce about, and there is so much about today’s world worth celebrating. But I wish that everyone could experience at least one season filled with the joy of discovery that I had in 1975, when I saw so many of my first birds through eyes filled with a child’s elation and wonder. The more we appreciate this world’s real life treasures, the more likely it is that we’ll protect them so young people of the future will also be able to thrill at a glorious season of discovery.